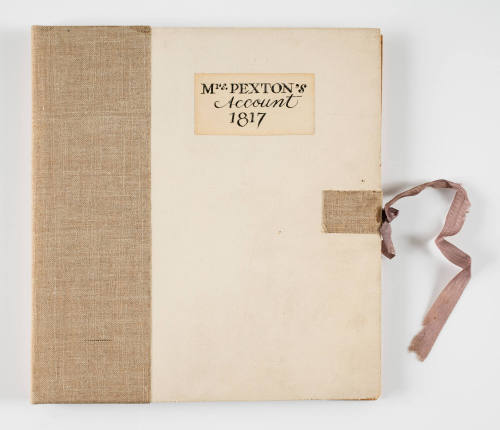

Mrs Pexton's diary on board the convict transport PILOT

Author

Mrs Pexton

Date1816

Object number00045200

DCMITypeStill image

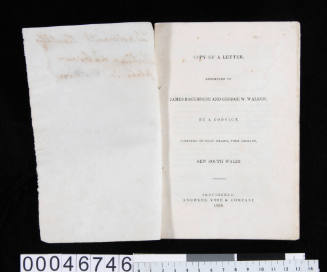

NameDiary

MediumInk on paper, cloth covered with ribbon tie

DimensionsOverall: 255 × 240 × 13 mm, 495 g

Copyright© Mrs Pexton

ClassificationsBooks and journals

Credit LineANMM Collection

Collections

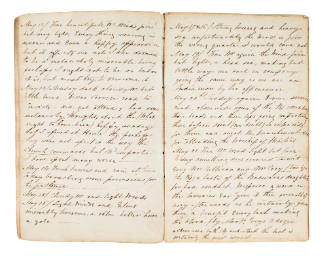

DescriptionThis diary was written by Mrs Pexton who accompanied her husband Captain William Pexton on board the convict transport ship PILOT, travelling from Cork, Ireland to Sydney, New South Wales. The ship held 120 male convicts and their guards. The journal provides an informative, witty and insightful account into the seven-month voyage, with substantial notes on life in New South Wales and the return journey to England.

HistoryUntil the early 19th century prisons were administered locally and were not the responsibility or property of central government, with the exception of King's Bench, Marshalsea, Fleet Prisons and Newgate Gaol which were all Crown prisons attached to the central courts. Prisons were used for the correction of vagrants and those convicted of lesser offences, for the coercion of debtors and for the custody of those awaiting trial or the execution of sentence.

For nearly all other crimes the punishments consisted of a fine, capital punishment or transportation overseas. From the early 1600s European societies used the transportation of criminals overseas as a form of punishment. When in the 18th century, the death penalty came to be regarded as too severe for certain capital offences, such as theft and larceny, transportation to the British colonies in North America became a popular form of sentence.

The American War of Independence (1776-1781) put an end to the mass export of British and Irish convicts to America and many of the convicts in Great Britain's gaols were instead sent to the hulks (decommissioned naval ships) on the River Thames and at Portsmouth, Plymouth and Cork (Ireland) where they were employed on river cleaning, stone collecting, timber cutting and dockyard work while serving out their sentence.

In 1784, under the Transportation and Penitentiaries Act, felons and other offenders in the hulks could be exiled to colonies overseas which included Gibraltar, Bermuda and in 1788, the colony of New South Wales.

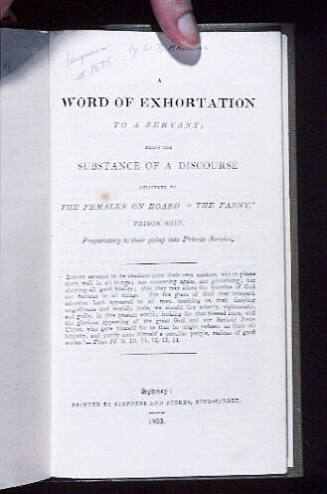

Between 1788 and 1868 over 160,000 men, women and children were transported to Australian colonies by the British and Irish Governments as punishment for criminal acts. Although many of the convicted prisoners were habitual or professional criminals with multiple offences recorded against them, a small number were political prisoners, social reformers, or one-off offenders.

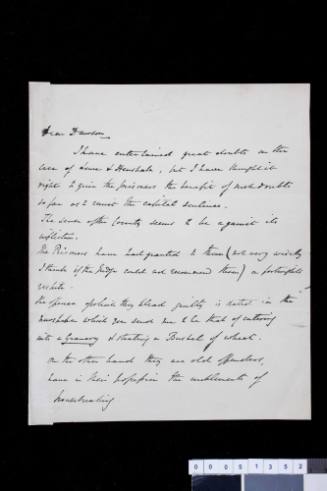

Mrs Pexton's diary is a very scarce handwritten account of a voyage to Australia, on the three-masted, 392 ton, Newcastle ship PILOT. It carried 120 male convicts from Cork, Ireland, with a military guard of a sergeant and 30 privates from the 46th and 48th Regiments under the command of Lieutenant Franklin of the 69th Regiment, to the penal colony of Port Jackson in New South Wales. Written by Mrs Pexton, wife of the ship's Captain William Pexton, the diary describes the seven-month voyage, from 18 December 1816, including a stopover in Rio de Janeiro and an attempted mutiny by the convicts. About half of the 75-page journal describes the voyage out and her sojourn in New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania). The penal colony had been established in New South Wales, at Port Jackson, in 1788 and the author gives an interesting, anecdotal account of the colony in its early days.

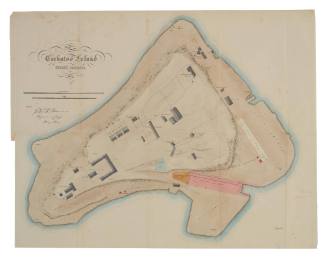

Arriving in July 1817 in Sydney, the author writes extensively of the town and vicinity, the social life, and the convicts along with descriptions of the inhabitants, and wildlife (including a tame kangaroo). Mrs Pexton then accompanied the PILOT transporting 280 convicts - 'The very worst which they can make nothing of at Sydney' - to Van Diemen's Land. Staying in Hobart, she describes the area and is relieved when her husband, Captain William Pexton, decides against buying a farm there.

Returning to Sydney, the transport ship took on a cargo of horses, and after the deposing of two convict stowaways, departed for Batavia (now Jakarta), Java. Storms, illness and a leaking ship forced the Pextons to take up residence in the city for several months, leaving on 7 May 1818. In her usual anecdotal style, Mrs Pexton gives a graphic description of the Dutch colony in about 12 pages - 'Pity it is so unhealthy for it is a beautiful country'.

With a cargo of rice, the PILOT next sailed for Port Louis, Isle de France (Mauritius), via Cheribon, India ('we got our muskets and arms ready...this coast is very much infested by pirates - frequently 200 together a boat...'. Again sickness and a leaking ship ('Mr. P. and the mate were obliged to assist in pumping night and day') necessitated a stay of about three months in British India. An often derogatory description of the colony is given.

Leaving India for England on 30 August 1818, the author writes some 12 pages on the voyage. The PILOT carried 58 time-expired British soldiers under a Lieutenant Gordon ('it was said he was mad'). Mrs Pexton gives a detailed description of St Helena and, although she did not see Napoleon Bonaparte, she gives several pages describing his situation on the island - 'he has lately been sullen refusing to speak to anyone - or go out of his house'. After a stop at the Ascension Islands, England was sighted on 26 November 1818. 'I have only been two years and am not able to express half the pleasure I feel at the sight of it...we shall be safe in London in a few days'. The journal is an insightful account by a very literate - and adventuresome - Englishwoman.

The PILOT was a three-masted, wooden ship of 392 tons that was built in Newcastle, England in 1814 for the ship broking firm of Clark and Company. The twin decked, copper sheathed vessel was given a rating of 12A1 at Lloyds - its highest rating. The ship was sold to the shipping company of Somes and Co in 1815 who then dispatched it to Batavia. On its return to England in 1816 the vessel was chartered to the British Government as a convict transport - an unusual occupation for a vessel ranked 12A1.

When the transport arrived in Port Jackson in July 1817, Charles Queade, the ship's surgeon-superintendent, forwarded to the Governor of New South Wales a copy of the instructions which he had issued to Captain Pexton and the Commander of the guard on board. As surgeon-superintendent Queade, obviously a man of some experience, was able to direct both the Captain and the Commander in all matters regarding the health, welfare and security of the convicts - including the order and number of guards on duty, the loading and placement of guns, possibly small cannon or swivel gins on the afterdeck pointing down into the waist of the ship, the arming of the ship's officers and placement of blunderbusses or muskets into the main and mizzen tops.

Queade also forbade soldiers and sailors from abusing, insulting or irritating the convicts, prohibited the trafficking of alcohol and tobacco, and oversaw the inspection of rations, ventilation, washing, hygiene and the securing of the convicts at night.

SignificanceThis is an extremely rare original account of life on board a convict transport ship. It is unusual having been written by a female passenger and a bystander to the events unfolding on the voyage. Although over 160,000 convicts were transported to Australia between 1788 and 1868, very few non-official diaries and journals of the convict voyages have survived.

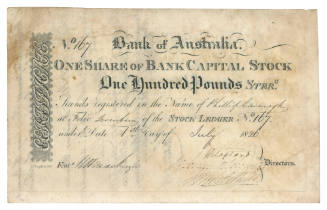

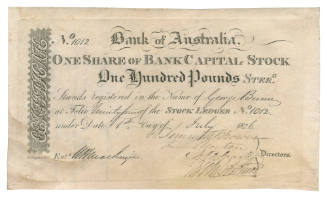

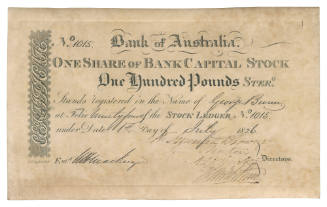

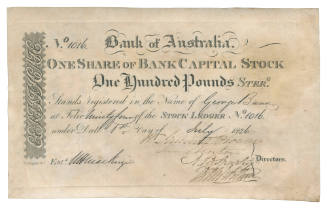

Captain George Bunn

1 July 1826