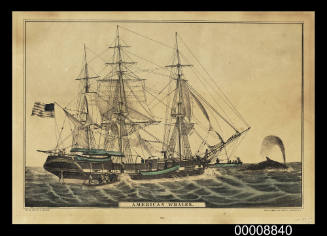

An East Indiaman laying-to in a gale

ArtistAttributed to a follower of

Francis Swaine

(British, 1725 - 1782)

Date18th Century

Object number00050192

NamePainting

MediumOil on canvas

DimensionsOverall: 406 x 703 x 40 mm

Image: 303 x 600 mm

Image: 303 x 600 mm

ClassificationsArt

Credit LineANMM Collection

DescriptionThis 18th century painting depicts a heavily-built vessel in strong wind. East India Company ships were well maintained and often of substantial tonnage, designed to transport their rich cargoes safely around the world.

Although unsigned, the painting appears to be by a follower of Francis Swaine (1720-1782). Swaine was a painter and draughtsman who worked as a messenger in the Navy Office in 1735. He was practising as a marine painter by the late 1740s, and regularly exhibited in the Free and Incorporated Societies of Artists from 1761.HistoryThe East India Company, also called English East India Company; Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies (1600-1708); was an English company created by Royal Charter on 31December 1600 to share in the East Indian spice trade. This trade had been a monopoly of Spain and Portugal until the defeat of the Spanish Armada (1588) by England gave the English the chance to break the monopoly. Until 1612 the company conducted separate voyages, separately subscribed. There were temporary joint stocks until 1657, when a permanent joint stock was raised.

The company met with opposition from the Dutch in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) and the Portuguese. The Dutch virtually excluded company members from the East Indies after the Amboina Massacre in 1623 (an incident in which English, Japanese and Portuguese traders were executed by Dutch authorities), but the company’s defeat of the Portuguese in India (1612) won them trading concessions from the Mughal Empire. The company settled down to a trade in cotton, silk, indigo and saltpetre, with spices from South India. It extended its activities to the Persian Gulf, South-East Asia, and East Asia.

After the mid-18th century the cotton-goods trade declined, while tea became an important import from China. Beginning in the early 19th century, the company financed the tea trade with illegal opium exports to China. Chinese opposition to this trade precipitated the first Opium War (1839–42), which resulted in a Chinese defeat and the expansion of British trading privileges; a second conflict (1856–60), brought increased trading rights for Europeans.

The original company faced opposition to its monopoly, which led to the establishment of a rival company and the fusion (1708) of the two as the United Company of Merchants of England trading to the East Indies. The United Company was organised into a court of 24 directors who worked through committees. They were elected annually by the Court of Proprietors, or shareholders. When the company acquired control of Bengal in 1757, Indian policy was until 1773 influenced by shareholders’ meetings, where votes could be bought by the purchase of shares. This led to government intervention. The Regulating Act (1773) and Pitt’s India Act (1784) established government control of political policy through a regulatory board responsible to Parliament. Thereafter, the company gradually lost both commercial and political control. Its commercial monopoly was broken in 1813, and from 1834 it was merely a managing agency for the British government of India. It was deprived of this after the Indian Mutiny (1857), and it ceased to exist as a legal entity in 1873. [Adapted from Encyclopaedia Britannica entry]

SignificanceThe East India Company was a major force in India and South-East Asia whose monopoly on trade in the area impacted on the early development of colonial trade in Australia. This painting depicts a typical East India Company vessel of the 18th century.

early-mid 19th century