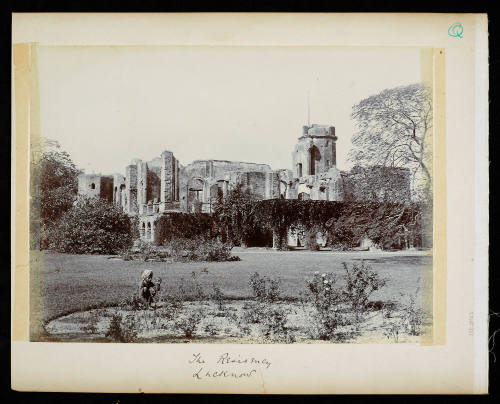

The British Residency at Lucknow

Datec 1899

Object number00026462

NamePhotograph

MediumPhotographic print on paper

DimensionsOverall: 207 x 283 x 1 mm

Mount / Matt size: 265 x 333 x 1 mm

Mount / Matt size: 265 x 333 x 1 mm

ClassificationsPhotographs

Credit LineANMM Collection

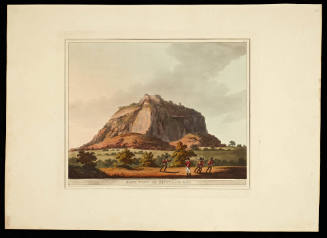

DescriptionTwo black and white photographs (adhered to the same board) of the ruins of The Residency at Lucknow in India. The buildings were also known as the British Residency or Residency Complex and was the residence for the British Resident General who was a representative in the court of the Nawab and were destroyed in the Indian Mutiny of 1857.

The first image shows a young boy tending to a garden in front of the the British Residency while the other image shows a close up of a set of ruins known as 'Dr Fayrer's House' anda plaque reading 'Here Sir H Lawrence died 4th July 1857'.

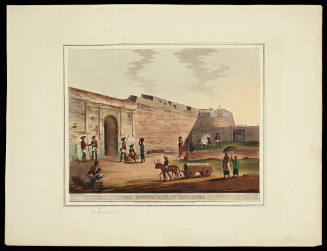

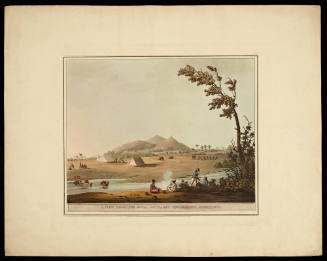

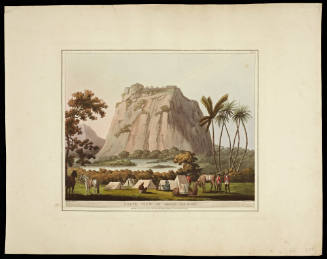

Through its trading activities and military campaigns, the East India Company grew to become the most powerful corporation in Asia. These images show the Kingdom of Mysore - home of Tipu Sultan, one of the Company's great opponents; and photographs of India in the second half of the 19th century.

HistoryThe English East India Company was granted a monopoly on all English trade east of the Cape of Good Hope and west of the Strait of Magellan by Queen Elizabeth in December 1600 and grew to become the most powerful corporation in Asia in the course of two and a half centuries. Initially formed with the intention to trade in pepper and spices in the Spice Islands (now Indonesian archipelago), it gradually focused its trading activities on India and trade in textiles, establishing major fortified 'factories' at Madras, Bombay and Calcutta in the late 17th century. The company's headquarters were in London where its Governor and Directors ostensibly controlled all its activities. However, in an era when voyages between England and India could take six months, company officials in India exercised considerable autonomy.

Originally titled 'The Governor and Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies', the company amalgamated with a powerful rival enterprise in 1709 and was thereafter called 'The United Company of Merchants Trading into the East Indies'. By the second half of the 18th century the decline in power of Mughal authority in India saw the rise of a number of independent rulers. When, during the Seven Years War (1756 - 1763) the Nawab of Bengal occupied Calcutta, holding company officers prisoner at Fort William, it triggered a military response under Robert Clive whose victory over the Nawab's forces at the battle of Plassey in 1757 resulted in the Treaty of Allahabad whereby the East India Company was granted the civil administration of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa - giving the company the right to tax over 20 million people. As a result of his victories, Clive was made governor-general of Bengal.

The company's new administrative responsibilities marked a radical change in its activities from trading company to governing ruler, administering ever-larger parts of the Indian subcontinent as the result of protracted military campaigns against the Marathas, Mysore and Sikhs. The change in the company's role was also marked by fierce debate in Britain where many politicians and merchants believed the company had become too powerful, and that the idea of trading monopolies was outdated. Public opinion against the company was heightened during the period when Warren Hastings was governor-general of Bengal (1773 - 1785). During this period around 5 million people died in Bengal as a result of famine and the company was mired in a number of expensive and inconclusive military campaigns. By 1784 the company had a debt of £8.4 million and was forced to ask the British government for help. The government ultimately agreed but through the East India Company Act (1784) it introduced sweeping changes which effectively saw it take responsibility for the affairs of the company in India. The Act raised the power of the Bengal Presidency over those of Bombay and Madras and made the governor-general of Bengal the supreme power in British India. Despite avowed political reluctance for further military campaigns, under the administration of Richard Wellesley (governor-general of Bengal 1797-1805) British control of India expanded greatly so that by 1815 around 40 million Indians were under British rule.

The 19th century brought increasing calls for an end to the company's monopoly, and in 1813 it lost its India monopoly, followed in 1833 by the end of its monopoly of British trade with China. In India, a long-growing dissatisfaction with company rule finally exploded in 1857 when a number of company regiments mutinied against their company officers, leading to uprisings in many parts of India. Known variously as the Indian Mutiny, India's First war of Independence or the Great Revolt, the uprisings marked the end of the East India Company's power. It was finally dissolved in 1874 but as a result of the Government of India Act 1858, the British crown assumed direct responsibility for governing India from that date. On 15 August 1947 India became a sovereign nation.SignificanceThese images reflect a broad spectrum of the British presence in India during the 19th century at a time when strong trade links existed between colonial Australia and India.

1850-1860