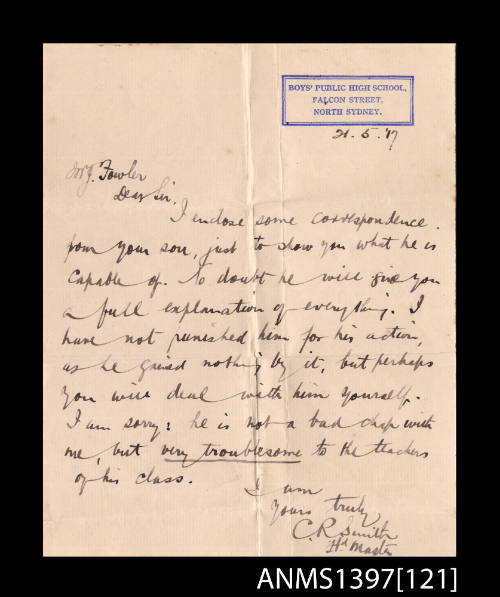

Letter from the Boys Public High School Master to Mr J.A Fowler

Author

William Simon Stewart Fowler

(Australian, 1903 - 1943)

Date21 May 1917

Object numberANMS1397[121]

NameLetter

MediumPaper, ink

DimensionsOverall: 240 x 190 mm

ClassificationsEphemera

Credit LineANMM Collection Gift from Wendy Thorvaldson

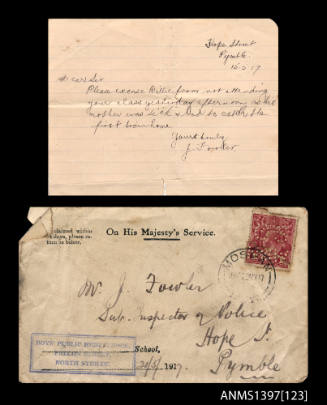

DescriptionHandwritten letter from the Boys Public High School Master to Mr Fowler dated 21 May 1917. The letter is to inform Mr Fowler that William has been 'very troublesome' to the teachers of his class.HistoryJohn Alexander Fowler was born in Elgin, Scotland in the 1870s and joined the Scottish Police Force before immigrating to Queensland in 1890. Fowler joined the New South Wales Police Force in 1894. In the early 1900s he was promoted to the newly established finger print branch of the force in Sydney. Fowler retired in 1926 with the rank of Inspector Superintendent of Detectives in the Criminal Investigation Bureau.

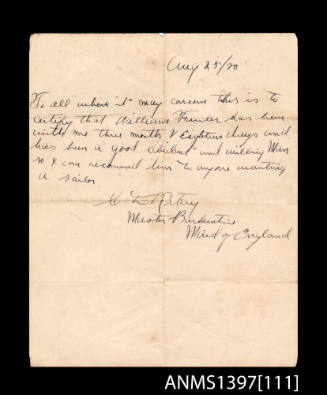

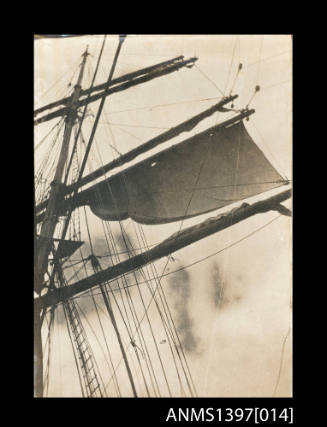

John Fowler's son William Simon Stewart Fowler was born in Sydney in 1903. William's early career was on sailing vessels - his second ship was the MAID OF ENGLAND a three masted barquentine. As the son of a forensic Police officer, Fowler was reasonably well educated and whilst at sea wrote long and descriptive letters to his father. His mother died in 1926.

By the 1930s Fowler had sat Master's exams and advanced to the rank of Second Officer. He joined the Moller Line - a small but expanding Hong Kong listed shipping company based in Shanghai - in January 1936 as Second Officer on the SS MARION MOLLER. Fowler was quickly promoted to Chief officer in March, then to acting Master in January 1937. A later reference from the Moller line was full of praise for his service with the company.

Fowler's career took an eventful turn when in April 1937 the MARION MOLLER was 'chartered for four months to a firm in London' as Fowler wrote in a letter to his father from Hamburg. He noted that 'it was originally intended for us to load in Hamburg after docking but later they changed their plans and we are now en route to Antwerp to load, I believe, a cargo of grain, destination unknown, but from hints dropped, I think it will be Spain.'

Fowler wryly noted that; 'Spain of course isn't too pleasant a spot just now, but one can't have everything and it is better than returning to the Orient as was first hinted and where I would most likely have been relieved by some senior Master and had to go back to Mate.'

Fowler's letters during this period, now in the Australian War Memorial collection, are an excellent and poignant record of events during the Spanish Civil War that an Australian sea captain became swept up in.

The Spanish Civil War began in Spain in July 1936 after a rebellion by a group of right-wing generals against the centre-left Republican Government and its supporters. The military arm of the rebel coup was led by General Franco.

Franco's forces received the support of Nazi Germany and the Kingdom of Italy, as well as neighbouring Portugal, while the Soviet Union intervened in support of the Republican government. The other major European powers remained neutral.

The Civil War became notable for the passion and political division it inspired around the world. Tens of thousands of civilians on both sides were killed for their political or religious views. It also became a testing ground for Adolf Hitler's German airforce, which most notably —and controversially— carpet-bombed the non-military target of the Basque town of Guernica in April 1937, killing hundreds of civilians.

The Spanish Republican forces were seriously hampered by the policy of non-intervention proclaimed by France and the United Kingdom. Although France in particular turned a blind eye, the importation of food and materials into Spain became a clandestine affair of running the Fascist naval and air blockade of the 3 mile Spanish territorial limit.

Many non-Spaniards joined the International Brigades, believing that the Spanish Republic was a front line in the war against fascism. Around seventy Australian men and women such as Joe Carter, a Port Kembla wharf labourer, and several nurses went to Spain during the Spanish civil war of 1936-1939.

There has been little attention paid the actions of the merchant vessels that ran the blockade during the civil war, and, until now, nothing widely known about the Australian sea captain and his Chinese crew that ran the blockade several times and rescued thousands of war refugees.

Wiliam Fowler was correct that his cargo vessel's destination was to be Spain. He wrote to his father on the 18th of May describing how the MARION left Antwerp with a cargo of foodstuffs, mostly grain. They stopped at Dover to take an observer aboard. All shipping near Spanish waters had to have an observor aboard to see that the '3 mile limit' was kept.

The MARION was protected by HMS SHROPSHIRE up to the limit and as the weather was hazy and there were no vessels in sight, Fowler took the MARION in to the port of Musel near Gijon in northern Spain. He described the poor condition of the people there, near to the front line of the war. After unloading, Fowler returned to England - he suspected for another run of food for northern Spain.

In June the MARION MOLLER once more ran the blockade and delivered food to northern Spain. At Gijon they took on a cargo and Fowler noted in a letter dated 28th June that it was 'just at this time that Bilbao fell and Santander was rapidly filling up with refugees - who were machine gunned by planes when fleeing to Santander.'

Fowler then arrived at Santander and took on refugees. All was proceeding well, despite constant air raids, until around 1am in the morning when 'the mob took charge' and 'the crowd surged forward and all count was lost.' At 5.30am Fowler refused to take any more passengers and left port - a later head count revealed 1,883 on board.

The events were described by Anne Caton in a pamphlet issued in Britain by the National Joint Committee for Spanish Relief in 1938:

'The captain [Fowler] who hoped to take the short trip to St. Jean de Luz, allowed 2,000 to fill the decks before sailing in the early hours of the morning. They were, however, not allowed to land at St. Jean de Luz and were obliged to proceed to La Rochelle. The ship was without accommodation or supplies of food. Two and a half days were spent at sea in cold, wet weather with nothing but scanty tarpaulins to cover the refugees on deck. The plight of the children was more than the men could bear witness; the officers and crew gave up all the accommodation available including their own cabins to the refugees, as well as all the food they had on board, and were themselves without food or shelter until the port was reached.'

It appears that the Spanish Relief Committee then approached Fowler as a sympathetic merchant captain. Anne Caton sailed with Fowler this time from Antwerp in July 1937 'with gifts of food from various societies'. Fowler does not mention this in his log and diary, only the official cargo on board, which had been purchased by the Asturias government. Fowler noted in his log book that the MARION MOLLER with a cargo of 78 Ford motors, was for many days 'unable to break the blockade of insurgent cruisers'. In fact, in a letter to his father on the 17th of July Fowler noted that apart from the cars, the vessel carried 'the greatest assortment of cargo possible' including flour, beans, cocoa, egss, car tyres, lard and salted cod.'

When the MARION MOLLER arrived off the Asturian coast, the rebel blockade had become more intense. Various French and British merchant ships were waiting outside Spanish territorial limits attempting to run the blockade. One British ship was fired upon and captured. The MARION MOLLER was also fired upon at one point, but a nearby patrolling British destroyer came to its rescue.

After two weeks of attempts, Fowler had almost given up hope when 'a break occured'. A Spanish Republican sea and air attack on the insurgents created an opportunity to run into the port and the MARION MOLLER followed another British vessel into Santander. The first vessel was bombed from the air and damaged, but just made it in to the port. With engines at full steam the MARION MOLLER - and what Fowler described as 'the longest 24 minutes I've put in', evaded shell fire from a distant ship and was greeted with 'wild cheering' from the crowds assembled on the quay. According to Caton, 'the captain had quite an ovation when he landed.' Fowler noted that the Spaniards in Gijon were wild with excitement' and that 'they badly needed our 6000 tons of food.'

After yet again running the blockade and then refuting charges that the vessel was carrying militia, Fowler embarked the refugees near La Rochelle in France and headed for Antwerp via London, expecting to make yet another trip to Spain.

However the ship's owners then turned down the proposition put to Fowler to take another 1,000 refugees out of Gijon. The MARION MOLLER left port uneventfully and headed to Falmouth to load with a cargo for Shanghai.

Caton pointed out the risks the merchant blockade runners met. The captains were at once responsible to their owners 'who order them to take no risks' and to 'the Spanish authorities who have purchased the cargo at great cost and are in desperate need of it.' As Fowler himself noted in a letter to his father on the 28th of May, ' I'm between the owners and the charterers and if anything goes wrong, it is the Master who carries the proverbial '"baby"'.

A copy of Caton's pamphlet 'The Martyrdom of the Basques' is in the collection of Fowler's material, including a 'with compliments of the author' slip. Fowler underlined a section where Caton wrote;

'An account has yet to be written about the courage and devotion of merchant seamen during the Spanish war.'

Yet it was not all a matter of courage and devotion - Fowler was most excited to later find 250 pounds sterling had been lodged in his bank account as 'credit for breaking the blockade' and he was 'very sorry to leave the Spanish trade when this money is circulating around.'

Still, Fowler obviously had an interest in the Spanish Basques and their struggle against the Franco led forces. He noted in one letter how 'things dont look too good for the Basques now that Bilbao has fallen, and I'm really sorry as I like the Basque people very much.'

Fowler then took the MARION MOLLER back to head offices in Shanghai. He went from one war to another, arriving in Shanghai just after the Japanese and Chinese forces had been fighting over the city at the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War in August 1937. Fowler noted the 'Japs parading around' and the 'packed troopships pouring up the Yangste bound for Hankow.'

The MARION was taken to Hong Kong and Fowler wanted to get back to Europe as he foresaw a major war in the East and that 'the Orient' would 'not be much good for any Europeans inside a few years - if not less.' He ended up in Japan however, and after anchoring in a bay whilst sheltering from a storm was put under arrest for 'entering a fortified zone.' He was placed under a guard, tried for espionage, and not released until extensively interrogated a few weeks later.

Fowler then did several cargo trips between various ports in China, French Indo-China and Japan - on one trip he noted the 'havoc and devastation' near Shanghai, with 'whole villages razed to the ground'. After 'a long spell' on the 'old Marion' - from January 1936 to April 1938 - Fowler had taken the MARION MOLLER into dry dock and was called up to take charge of the ROSALIE MOLLER, whose captain had been 'taken ill.'

After a short stint on the ROSALIE, Fowler was put in charge of the Moller line flagship the NILS MOLLER. In mid-1939 he suffered a bout of typhoid and after a recovering was about to take over another Moller vessel when war was declared and he volunteered for service in the Royal Navy. At Shanghai at the time, Fowler continued to work on cargo vessel runs through late 1939 and early 1940 - again running a blockade, this time the Japanese blockade of Chinese ports. But he was desperate to join the war effort in Europe and hoped that Moller's Line ships would be requisitioned by the British Navy.

In August 1940 Fowler got his wish and was transferred to the LILLIAN MOLLER which had just been requisitioned by the British government. In Calcutta in September 1940 the vessel was fitted with a 4 inch anti-aircraft gun and the crew all trained in its use. The Chinese crew members according to Fowler 'kicked up plenty of trouble' at this, 'wanting all sort of things, extra food, bonuses, etc.' Fowler wished for a 'reliable white crew'.

After taking on a cargo from Calcutta bound for Britain and joining a convoy at Cape Town in South Africa, Fowler's last letter to his father was written on the 24th October 1940 from Freetown, Sierra Leone.

On the 18th of November, the LILLIAN MOLLER had been dispersed from its convoy when it was torpedoed and sunk by the Italian submarine MAGGIORE BARACCA. There were no survivors. There were 42 Chinese crew members on board and 7 British officers. Ironically, Fowler's vessel was sunk by the Italians, whom he had often derogatively labelled 'dagos' in his letters home.

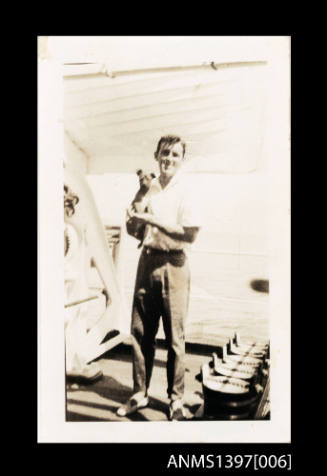

The collection of material William Fowler sent home to his father over his years on the 'China Coast' and in the Atlantic includes photographs taken by Fowler of various vessels and ports visited, as well as postcards and letters written to his family, during his merchant career in the 1920s and 1930s. There is also a 'A Diary of the Ship CLAVERDEN from Durban South Africa to Cette, France'. Fowler illustrated the front page with a crude drawing of the vessel.

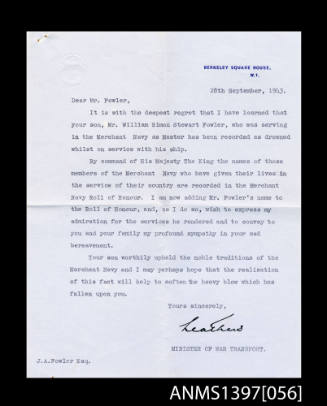

Significantly, the material includes the telegram sent by the Minister of War Transport informing John Fowler that his son William 'who was serving in the Merchant Navy as a Master has been drowned whilst on service with his ship.' The letter is dated 28th September 1943. Fowler was was 37 years old when he died.

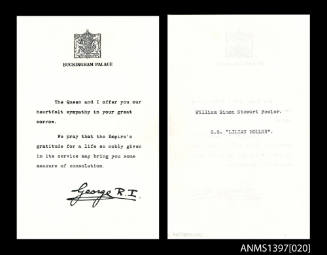

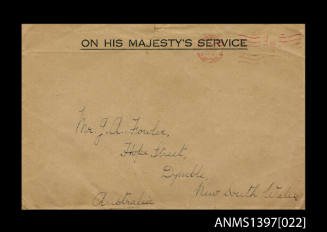

The collection also includes a telegram from King George the VIth in its original packet labelled 'On His Majesty's Service' which states;

'The Queen and I offer you our heartfelt sympathy in your great sorrow. We pray that the Empire's gratitude for a life so nobly given in its service may bring you some measure of consolation.'

Sources:

Amirah Inglis (ed) Letters from Spain - Lloyd Edmonds George Allen & Unwin, Sydney 1985

Amirah Inglis, Australians in the Spanish Civil War, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1987

Australian War Memorial Commemorative Roll, http://www.awm.gov.au/research/people/commemorative_roll/person.asp?p=565989

'SS Lilian Moller' Convoy Web, http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/sl/mem/53_3.htmSignificanceThe collection of correspondence and other material from William Fowler to his father during the Spanish Civil War is both a rare and rich example of the connections between Australians and the war in Spain. Australian volunteers to the International Brigades that fought in Spain are known and commemorated. Australian merchant shipping crews who ran the naval blockades in northern Spain during the war are not widely known, nor commemorated.

Fowler's other memorabilia and letters that describe his period working for the Moller line on the 'China Coast' are also a rare and a excellent picture of this little known period during which trade was still conducted with Japan as it fought China and expanded its empire in Asia just before World War II.

The collection is particualrly poignant as it ceases when Fowler's Defensively Equipped Merchant vessel LILLIAN MOLLER was torpedoed and sunk with the entire loss of 49 crew on its first journey into the Atlantic during the war.

William Simon Stewart Fowler

28 September 1943

William Simon Stewart Fowler

1910 - 1940

William Simon Stewart Fowler

1910 - 1940

William Simon Stewart Fowler

1910 - 1940

William Simon Stewart Fowler

1910 - 1940