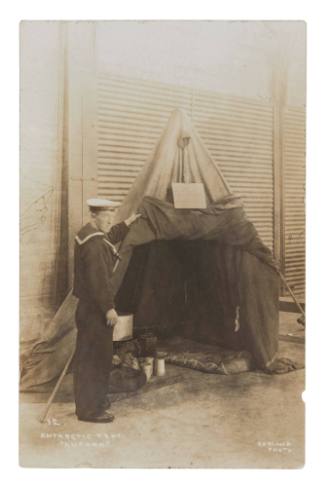

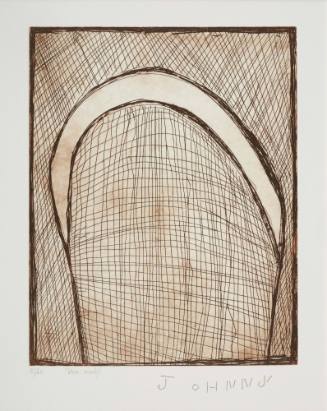

Drawing of men camping under a boat, the Snuggery, on Elephant Island

Photographer

Captain Frank Hurley

(1885 - 1962)

Artist

George B Marston

(English, 1882 - 1940)

Datec 1916

Object number00054092

NameLantern Slide

MediumGlass, ink on paper

DimensionsOverall: 82 x 83 x 3 mm

ClassificationsPhotographs

Credit LineANMM Collection

DescriptionA black and white slide showing an interior view of the makeshift 'hut' on Elephant Island. The image is a composite of photograph by Frank Hurley and drawing by George Marston. The inside measurements by thge Snuggery was 18 feet by 9 feet by 5 feet at its highest point.

The 22 men, under the command of Frank Wild, waited four and a half months for Shakleton's return.

The shelter was built on guano-covered rocks – the site of a penguin rookery exposed to terrific winds and blizzards. Gaps were plugged with old sleeping bags and ice, and nailed tent canvas to the boat gunwales like a valance, anchoring it with rocks. Crammed in, sleeping on boat thwarts and the ground, they grew filthy, continually wearing the same clothes, coated in reindeer hair from their sleeping bags, and with soot, smoke and blubber spewing from the small stove – all during the darkness of the Antarctic winter.

This is from a collection of glass lantern slides assembled by Charles Reginald Ford, Chief Steward on Scott's DISCOVERY expedition, and used by him in talks about the various British expeditions to Antarctica during the so-called heroic age in the early twentieth century.

HistoryShackleton had left his trusted friend, Antarctic veteran Frank Wild, as leader of the 21 men on Elephant Island.

On guano-covered rocks – the site of a penguin rookery exposed to terrific winds and blizzards – they built a shelter from the two upturned lifeboats. They plugged gaps with old sleeping bags and ice, and nailed tent canvas to the boat gunwales like a valance, anchoring it with rocks.

The men named their tiny home ‘the snuggery’ and ‘the sty’. Crammed in, sleeping on boat thwarts and the ground, they grew filthy, continually wearing the same clothes, coated in reindeer hair from their sleeping bags, and with soot, smoke and blubber spewing from the small stove – all during the darkness of the Antarctic winter.

The men talked of food and tobacco, smoking all sorts of concoctions: grass shoe insulation, seaweed, reindeer hair and tea. They played cards, read, discussed entries from volumes of the Encyclopaedia Britannica they had salvaged, sang and made snowmen.Their diet was meagre. They had brought limited stores of sledging biscuits, sugar, salt, powdered milk and nutfood (ground nuts and sesame oil) – all carefully rationed for the first months until stocks ran out. They hunted and skinned wildlife or collected shellfish. Thomas Orde-Lees noted in his journal on 3 May 1915:

At present we are merely living hand to mouth and have yet only a small reserve. We were certainly lucky to have got here no later than we did, for we got in a fair stock of seal meat before the seals left us which they seem to have done now, There is enough seal meat for six weeks.

Their alcohol supply was methylated spirits, intended as fuel for the primus stove but released by the tablespoon with a spoon of sugar for the customary Saturday toast ‘to sweethearts and wives’.

A lack of carbohydrates caused lethargy, and several of the men suffered physically in other ways – the stowaway, Perce Blackborow, at 19 the youngest member of the crew, developed such extreme frostbite that his toes were amputated in the makeshift hut. Yet the mental challenges were far worse. Several men were unable to function, being confined to their sleeping bags. Cliques developed within the group, yet quarrels were few, with all men united in daily survival routines.

As weeks rolled into months, the marooned men began planning to launch one of their boats, not knowing if Shackleton had made it to safety. Then on a gloomy 30 August, artist George Marston was out sketching with photographer Frank Hurley when they saw a ship on the horizon. The men lit a fire and raised makeshift flags. Soon after, the familiar figures of Shackleton, Worsley and Crean came into view aboard the Chilean naval tug Yelcho. This was Shackleton’s fourth attempt to reach the stranded men. Ice had thwarted previous attempts.

On deck the scientists and officers ate apples and oranges, eager for Shackleton’s news of the war; down below the sailors feasted, drank and indulged tobacco cravings with pipes and cigarettes.

The wild-looking party reached Punta Arenas, Chile, on 3 September 1916, where they were feted for two weeks. Visitors flocked to see the ‘frostbitten boy’ Perce Blackborow in hospital. They then made their way to Buenos Aires to ship back home.

SignificanceThe collection of slides of Antarctic voyages compiled by Charles Ford documents aspects of the technical and geographical mapping work, personal challenges, daily lives, social dynamics and the landmarks, icescapes, waterscapes and environments the men encountered.

1901 - 1904

1901-190