Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

Subject or historical figure

Sir Lionel Hooke

(Australian, 1895 - 1974)

DateDecember 1914

Object number00055431

NamePhotograph album

Mediumpaper, photographs

DimensionsOverall (closed): 178 × 238 × 12 mm, 338 g

Overall (open): 477 mm

Overall (open): 477 mm

ClassificationsPhotographs

Credit LineAustralian National Maritime Museum Collection Gift from Maria Teresa Hooke OAM and her sons John Max and Paolo in memory of John Hooke CBE and Sir Lionel Hooke

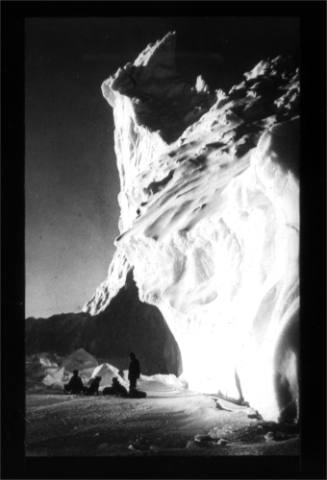

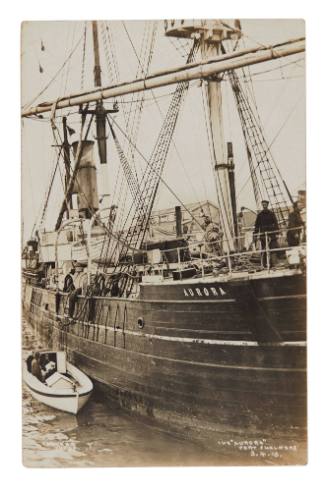

DescriptionA photographic album containing 86 images of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Imperial Transantarctic Expedition, December 1914. The photographs show images of the Antarctic landscape, of the crew, dogs, penguins, seals and the ship. Almost all photographs were taken or sourced by Sir Lionel Hooke, wireless operator aboard the SY AURORA, between 1914-1916.

The album captures the voyage south, the sledging dogs (including Hector, Duke, Jack Jock & Kanuk and Towser), penguins, seals, the ship in the ice, from the masthead, on board, from the ice, in all weather conditions, the blizzard, arrival in Antarctica - the ice barrier, the mainland, glaciers, landforms, icefields, ice, the vessel after its tore its moorings in May 1915, on board midwinter day July 1915, the broken rudder, the sea galley on the ice during the vessel’s entrapment, ice pressure, the wireless aerial, and the crew and expeditioners on the stern, on board after AURORA's safe arrival in Port Chalmers on 3 April 1916.

HistoryLionel Hooke was the wireless operator on SY AURORA, the Ross Sea Party's supply ship for Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial-Trans Antarctic Expedition of 1914-17. Then only 18 years old, Hooke left from Hobart in late December 1914 to McMurdo Sound, Antarctica, with the party tasked by Shackleton to sledge inland to lay deposits for him and his crossing party approaching from the Weddell Sea.

Hooke took part in sledging operations until AURORA broke its moorings during a blizzard in May 1915, abandoning ten of the supply party still ashore at McMurdo Sound including expedition leader Mackintosh. Hooke was one of 18 men marooned on the ship, now under the command of former first mate Joseph Stenhouse and trapped, drifting in ice for nine months.

Hooke finally established wireless contact with the Naval Radio Station at Williamstown Victoria as the vessel limped towards New Zealand. The ship was at the time at least five times more distant than the normal range of its transmitting equipment. Aurora finally arrived in Port Chalmers, New Zealand in April 1916.

According to a report in the New York Times 14 May 1916 Hooke was widely applauded for his persistence, his resourcefulness and his inventiveness in continually overhauling his limited equipment, especially when jury-rigging an aerial to ice hummocks after a blizzard after Aurora was dismasted and the aerial carried away on 5 September.

Hooke later sailed to the UK to enlist in 1916, in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve and later the Royal Naval Air Service where he was trained as a pilot for the RNAS airships escorting convoys and patrolling for enemy submarines and mines.

Returning to Australia in 1919, Hooke joined Amalgamated Wireless Australasia where his interest in research and development saw him transmit the first live radio broadcast to legislators 12 miles away in Victoria's Parliament in 1920, oversee direct wireless telegraphy between Australia and the UK and the re-equipping and reorganisation of the Australian coastal radio network which AWA acquired in 1922. He also designed the automatic distress transmitter (patented 1929) which enabled emergency messages to be sent from ships that did not carry a radio operator. It was a forerunner to the EPIRB. During WWII he channelled AWA's resources to communications for Australian and American forces in the Pacific.

In 1945 Hooke became managing director and in 1962 succeeded his friend and mentor Sir Ernest Fisk as chair of AWA. He was awarded a knighthood in 1957 for his services to industry and coronation medals in 1937 and 1953.

SignificanceThese photographs, although somewhat faded, are personal views that offer valuable insights into the trajectory of the expedition from the optimism of formal crew portraits leaving Hobart in 1914 with its mission to lay supplies for Shackleton's trans-polar party, to AURORA's loss to the expedition from May 1915 to March 1916 and its eventual safe docking on terra firma in Port Chalmers.

Joseph Russell Stenhouse

27 March 1916

William Hall Photographic Studio

December 1914

Joseph Russell Stenhouse

1916

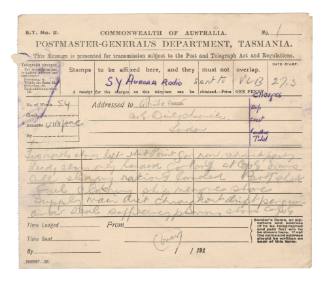

![Telegraph to Stenhouse, Barrow in Furness, England, from [Joseph] Russell Stenhouse on SY AURORA](/internal/media/dispatcher/237099/thumbnail)