Employment Contract for Pearl Shell Fishery

Date14 October 1931

Object number00056166

NameContract

MediumPaper

DimensionsOverall: 315 × 207 mm

ClassificationsEphemera

Credit LineAustralian National Maritime Museum Collection gift of Lindsey Shaw

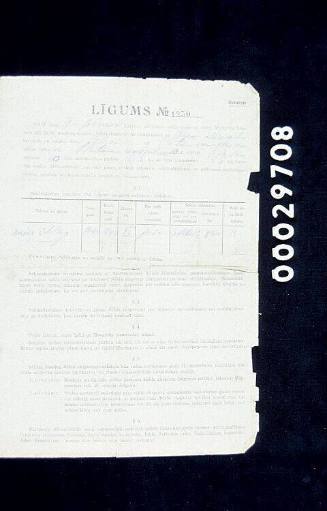

DescriptionFour page contract for Mataichiro Kawamoto allowing him to travel to Thursday Island from Japan to work as a seaman, on a pearl shell lugger. The contract signed in Kobe, Japan, through a recruiting firm Kaigai Kogyo Kaisha, (Overseas Industrial Company) outlined the terms of the employment, accommodation, quantity of food, holidays, medical provisions, and length of the employment.

The contract was a formality with the Australian and Japanese Governments to safeguard the employee against exploitation but was understood to not be binding. On arrival in Australia the employee signed another contract and then the ship’s articles which governed expectations and behaviour on board the boat they were assigned.

HistoryPearl shelling as an industry

A major industry for Australia from the late 1860’s to the early 1960’s the collection of Mother-of-Pearl, Trochus shell and Beche-de-mer. Found in the tropical north waters of Australia, the South Sea pearl oyster (Pinctada maxima)—had been traditionally collected and traded by local by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. European colonists in North Western Australia became interested in the material found within the shells in 1850’s. By the early 20th century, Australia was supplying 75 per cent of the world's pearl shell.

Pearl shell was a valuable material before the days of plastic, and sold for £150 per ton in Sydney in the 1860s.The shell was used to make cutlery handles, buttons, decorative inlay in furniture, watches and instruments, jewellery and even belt buckles. By the late 1860’s collection of the Mother-of- Pearl shell, the Trochas shell (also used in the manufacturing of similar goods) and Beche-de-mer (sea cucumber, popular in Asian countries such as China, Malaysia, Hong Kong and Taiwan, consumed as a delicacy and for its perceived medicinal properties) were regularly harvested for export. Naturally occurring pearls were rarely found and were considered a bonus.

Broome in Western Australia, Darwin in the Northern Territory and Torres Strait Island in particular Thursday Island became key Pearl Shell Industry communities, with the production value ranging from £167,000 in 1900 to on average to mid-1940’s £300,000 per year (Jennison,1946). Initially the collection of the shell was picked from the bottom of shallow waters in depths of up to 8 fathoms by free divers, (predominately South Sea Islanders), using small boats close to the coastal communities. However, as the industry expanded, competition increased the need to seek new offshore beds. To accommodate this, larger boats that could remain at sea for increasing periods were built.

The use of hard-hat diving suits and equipment developed in the 1830s by Augustus Siebe became widespread on Australian pearl luggers in the 1880s. By pumping air from the boats, the new diving suit allowed divers to descend to 15 fathoms. Onboard the boats, the focus was now on the productivity and ability of the dress diver, who was better trained and more highly motivated than swimming divers. Malay and Filipino divers were originally recruited and rewarded with incentive payments, but by the 1890s Japanese divers and tenders dominated the top end of the pearling workforce. (Ganter, 2010)

The diving season was limited by the monsoon period and springtides, so divers increased their catch by extending the number and length of dives while conditions were favourable, increasing the risk of divers’ bends (decompression sickness). The dangerous occupation, claimed the lives of 10% in the industry (in 1916, compared to an overall occupational death rate of 1.1% in Queensland), making the occupation very unattractive for European employees as the top income was less than a farmworker’s minimum wage, however it was still very attractive for young men from impoverished villages in Japan and South-East Asia.

After the federation of the Australian colonies in 1901, immigration became a particular focus for the new government. The government through the Immigration Restriction Act 1901, tried on several occasions to replace the cheaper foreign labour with white labour however, the high risk and the low pay meant that the they had trouble attracting suitable workers. European master pearlers from Thursday Island defended their access to cheap imported labour successfully, and the foreign workers could be given permission for temporary entry, only if they came under a contract of indenture.

Under the terms, the employer covered the cost of passage to Australia, paid a bond to the Queensland Government to ensure that the foreign employee would not seek other employment outside the pearl shell industry and the employer would repatriate the employee to their home port at the end of their 3 year contract. Often at the end of the contract the employee would re-sign or move to another pearling company staying for several years. The pearling masters supported the idea that foreign workers could not own boat licences. As a result, the entrepreneurial end of the fishery remained in the hands of whites, whereas the workforce consisted entirely of Asian, Pacific, and Indigenous people. (Ganter,1994)

Money was a key incentive reason for the Japanese men to work on the boats. Japanese custom meant that the older son inherited all property, therefore the younger sons had to find ways of earning enough money to set up their own house. The men did not come to settle in Australia, but to make money then return home to family and traditional lower paying employment of fishermen and farmers. The quickest way to do this was to spend a few years working in the Pearl Shell industry, with the aim of becoming a diver, a position of prestige with many privileges. New recruits were taken on as crewman on the ships to man the pump handle, cook and help run the boat with wages much less than a diver. It was from here that the new divers were recruited and if showed potential were encouraged to learn as a try-diver. It could take up to 3 years to become an effective diver that could be sent out on solo dives. The goal of all the crew, was to be able to collect as much shell as possible. (Sissons,1979)

After 1901, the process undertaken by a Japanese man seeking employment on a Thursday Island pearl shell boat would be to register their interest with relatives or friends already working in Australia. Then wait for the captain to submit their interest to one of the owners, who would then send a request for labour to a recruiting firm in Japan. In the case of this contract the Kaigai Kogyo Kaisha (Overseas Industrial Company). The recruit would have then travelled to Kobe to undergo medical examinations, sign the contract and would have been issued with an identification certificate with two photographs and a copy of their handprint valid for the purpose only of working in the pearl shell industry. (Iwamoto,1999)

The contract outlined the terms of the employment, quantity of food provided to the employee, holidays, medical and length of the employment including clauses about accommodation. The contract was a formality with the Australian and Japanese Governments to safeguard the employee against exploitation but was understood to not be binding. On arrival in Australia the employee was asked to sign another contract and the ship’s articles which governed expectations and behaviour on board the boat they were assigned. (Ganter,1994)

The Japanese pearl shell workers lived on board their boats but came to shore during the layup period or monsoon times December to April. Due to their status as foreigners, the Japanese on Thursday Island were excluded and they stayed in the insular Japanese settlement of Yokohama, which included three Japanese shops, a boarding house eateries and billiard halls, a laundry and clubhouse and some family homes. During the months of the layup the community on the Island expanded quickly. (Nagata, 2004)

When Japan entered the war in 1941 all the Japanese nationals on Thursday Island were interned by the Government. At first in the township of Yokohama (surrounded by barbed wire and guarded by soldiers) then they moved the pearl shell employees to the internment camp in Hay, NSW. After the war they were repatriated back to Japan. It was not until 1958 that 106 men from Okinawa were permitted to come and work to try to revive the pearl shell industry.

By the 1960’s the increasing use of plastic in the manufacture of buttons and the continuing depletion of stock, that had not been sustainably collected and not replenished, meant that the pearl shell industry declined even further to now being no longer economically viable as an export industry.

Bibliography

Ganter, Regina. (2010) Pearling: Queensland Historical Atlas https://www.qhatlas.com.au/content/pearling accessed December 2020

Ganter, Regina. (1994). The pearl- shellers of Torres Strait Resource Use, Development and Decline: Melbourne University Press: Melbourne

Iwamoto, Hiromitsu.(1999) Nashin: Japanese Settlers in Papua and New Guinea 1890-1949

in The Journal of Pacific History. JPH Canberra

https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/132632/1/JPH_Nanshin.pdf

accessed December 2020

Jennison, A. (1946). Labour in Australian Pearl-shell Fisheries in Fisheries Newsletter Vol 5 No.3 June.

Nagata, Yuriko.(2004). Chapter 6 The Japanese in Torres Strait in Navigating Boundaries: The Asian diaspora in Torres Strait

http://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/n3973/pdf/ch06.pdf accessed December 2020

Sissons, D, C, S. (1979) The Japanese in the Australian pearling industry; in Bridging Australia and Japan: The writings of David Sissons, historian and political scientist Edited by: Arthur Stockwin, Keiko Tamura Volume 1. Australian University Press. https://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/n2207/pdf/book.pdf accessed December 2020

SignificanceThe pearl shell, Trocas shell and Beche de Mer industry that was a major export from Australia between 1860 – 1960 and employed a number of Japanese workers such as Mataichiro Kawamoto. Many of these workers immigrated to Australia.