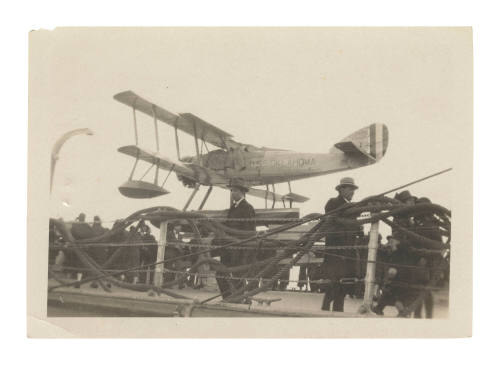

Vought UO 1 seaplane aboard USS OKLAHOMA

Date1 July 1925 - 31 August 1925

Object number00056610

NamePhotograph

MediumPhotographic print on paper

DimensionsOverall: 59 x 84 mm,

ClassificationsPhotographs

Credit LineAustralian National Maritime Museum Collection

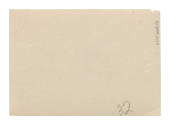

DescriptionOver July–August 1925, Sydney was visited by 11 US Navy vessels (including eight battleships) while Melbourne simultaneously welcomed 38 warships and support vessels. Although ostensibly a goodwill tour in the aftermath of World War I and the 1922 Washington Treaty, this massive fleet manoeuvre also demonstrated American naval predominance to Australia, Britain and Japan. This photograph depicts a Vought UO-7 floatplane on the rear deck of USS OKLAHOMA during its sojourn in Melbourne. It encapsulates both American naval predominance in the 1920s and the US Navy’s focus on enhancing performance through emerging technologies, such as the use of aircraft for reconnaissance and gunnery spotting.HistoryThe 1922 Conference on the Limitation of Armament in Washington, DC, formally dissolved the Anglo-Japanese Alliance that had been in place since 1902. In its stead, the so-called ‘Washington Treaty’ prompted a pronounced reduction in naval tonnage for the five participating powers: Great Britain, the USA, France, Japan and Italy. The nations with interests in the Pacific Ocean subsequently signed a ‘Four-Power Treaty’, ratified in 1923, which sought to address geostrategic concerns in the region via diplomatic means (United States Department of State, ‘Conference on the Limitation of Armament, Washington, November 12, 1921 ‒ February 6, 1922. Treaty Between the United States of America, the British Empire, France, Italy, and Japan, Signed at Washington, February 6, 1922’, in Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, Volume 1 [Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1922], pp.247‒66).

In reality, the Washington Treaty escalated both racial and military tensions by leaving Japan distrustful of Britain’s loyalties and openly discriminated against by America, especially following the passage of the US Exclusion Act 1924, which limited Asian immigration. There were also underlying concerns both in Britain and America about each other’s long-term ambitions in the Pacific, especially with the UK investing heavily in a fortified naval base in Singapore – the only new such facility permitted under the treaty. In Australia, elements within the Federal Government and Royal Australian Navy questioned whether Royal Navy fleet units would reach Singapore from Britain in time to deal with aggressive naval forays by Japan or, more remotely, the USA. Nevertheless, the fundamental naval tension in the Pacific in the decades after World War I was between America and Japan, initially in the realm of battleships but increasingly via the technical and tactical development of aircraft carriers (Naoko Sajima and Kyoichi Tachikawa, Japanese Sea Power: A Maritime Nation’s Struggle for Identity [Canberra: Sea Power Centre – Australia, 2009], pp.39–46).

One corollary of this posturing was a sequence of naval visits to major ports in Australia and New Zealand. From December 1923 until February 1924, a Japanese squadron comprising the cruisers HIJMS YAKUMO, ASAMA and IWATE toured Fremantle, Melbourne, Hobart, Sydney, Wellington and Auckland (National Archives of Australia, Series MP138/1 Control 603/203/38; Australian War Memorial AWM61 542/1/14). A British Special Service Squadron also included Australasia as part of its 1923–24 world cruise, calling at Fremantle, Albany, Adelaide, Melbourne, Hobart, Jervis Bay, Sydney, Brisbane, Lyttleton, Wellington and Auckland over February to May 1924. This squadron was led by the flagship of the Royal Navy, HMS HOOD, in company with a second battlecruiser, HMS REPULSE, plus five destroyers: DELHI, DUNEDIN, DANAE, DAUNTLESS and DRAGON. When it departed Sydney, the squadron was accompanied for the remainder of its voyage by the first major warship built in Australia, the light cruiser HMAS ADELAIDE. This gesture demonstrated a display of imperial cooperation and interoperability that typified the interwar period (V.C. Scott. O’Connor, The Empire Cruise [London: Printed privately for the author by Riddle, Smith & Duffus, 1925]; C.R. Benstead, Round the World with the Battle Cruisers [London: Hurst and Blackett, 1925]; Rohan Goyne, ‘“The Booze Cruise”: an episode in the peacetime history of the Royal Navy 1923–1924’, Sabretache 51, no. 2 [2010]: 23–26; John C. Mitcham, ‘The 1924 Empire Cruise and the imagining of an imperial community’, Britain and the World 12, no. 1 [2019]: 67‒88).

Not to be outdone, in 1925 the US Navy also detached a major fleet unit to visit Australia and New Zealand. Their Australasian sojourn followed a month of exercises in the Pacific to the southwest of Hawai’i. Over July and August, elements of this massive deployment visited Sydney, Melbourne, Hobart and Auckland. Under Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Robert E. Coontz, the US fleet consisted not only of capital ships, cruisers and destroyers, but the specialised auxiliary vessels that permitted them to foray for months beyond American shore facilities. An estimated crowd of 500,000 lined Sydney Harbour to receive the flagship of the battle fleet, USS CALIFORNIA (BB-44), plus seven other battleships: NEW MEXICO (BB-40), MISSISSIPPI (BB-41), IDAHO (BB-42), TENNESSEE (BB-43), COLORADO (BB-45), MARYLAND (BB-46) and WEST VIRGINIA (BB-48). They were accompanied by the hospital ship RELIEF (AH-1), repair ship ARCTIC (AF-7) and oiler CUYAMA (AO-3) (‘Uncle Sam’s battleships: their various types’, Evening News, 22 July 1925, p.5). Melbourne hosted Admiral Coontz’s flagship, the 1906-vintage armoured cruiser USS SEATTLE (CA-11) plus five light cruisers of more recent design: OMAHA (CL-4), RICHMOND (CL-9), TRENTON (CL-11), MARBLEHEAD (CL-12) and MEMPHIS (Cl-13). They were accompanied by the battleships NEVADA (BB-36), OKLAHOMA (BB-37) and PENNSYLVANIA (BB-38), plus two destroyer squadrons comprising McDERMUT (DD-262), SINCLAIR (DD-275), MOODY (DD-277), PERCIVAL (DD-298), JOHN FRANCIS BURNS (DD-299), SOMERS (DD-301), STODDART (DD-302), FARQUHAR (DD-304), THOMPSON (DD-305), KENNEDY (DD-306), PAUL HAMILTON (DD-307), YARBOROUGH (DD-314), SLOAT (DD-316), WOOD (DD-317), SHIRK (DD-318), KIDDER (DD-319), MERVINE (DD-322), CHASE (DD-323), ROBERT SMITH (DD-324), MULLANY (DD-325), MacDONOUGH (DD-331), FARENHOLT (DD-332), SUMNER (DD-333), MELVIN (DD-335), LITCHFIELD (DD-336) and DECATUR (DD-341). They were serviced by the destroyer tenders MELVILLE (AD-2) and ALTAIR (AD-11), plus floating workshop MEDUSA (AR-1) (‘Latest developments in fast cruisers’, Herald, 23 July 1925, p.7). Hobart subsequently enjoyed a visit by the cruisers TRENTON, MARBLEHEAD, RICHMOND and MEMPHIS (‘American cruisers due at Hobart today, Mercury, 5 August 1925, p.10).

Although its cultural impact was not as pronounced as either the US Great White Fleet of 1908 or the preceding year’s British Special Service Squadron, this was the most extensive and powerful naval force seen in Australian waters until the final stages of World War II (Justine Greenwood, ‘The 1908 visit of the Great White Fleet: displaying modern Sydney’, History Australia 5, no. 3 [2008]: 78.1–16; Peter M Sales, ‘Going down under in 1925’, US Naval Institute Proceedings 111 [1985], pp.45–53). The fact that the US Navy comfortably divided its forces to overwhelm both Sydney and Melbourne simultaneously sent a clear message about burgeoning American naval might, compared with the mere seven British vessels that had arrived in 1924. This point was certainly received in Japan, despite the observations of one British observer aboard USS PENNSYLVANIA in Honolulu before the cruise began. ‘There is no fear of an American-Japanese war in the near future’, he opined. ‘America does not want it, and Japan will not force it, as it would lead to her losing her best market and bring her no rewards worth fighting for’ (McCullagh, Francis. ‘The Question of the Pacific: A Letter from the American Fleet’. Blackfriars 6, no. 65 [1925]: 463‒7). While the major presence of two American battle groups was largely welcomed by Australians, there were also both imperial-minded and labour protests in both Sydney and Melbourne (Russell Parkin, Great White Fleet to Coral Sea: Naval Strategy and the Development of Australian–United States Relations, 1900–1945 [Manuka: Wilton Hanford Hanover, 2008]). Contact with ordinary American sailors also created unexpected racial tensions. ‘Australians living in a country in which the “white-man” policy is as strong as it is here, failed to comprehend how negroes [sic], Filipinos and seeming-Japanese, could be wearing the uniform of Uncle Sam’, wrote one American naval officer, adding ‘Considerable explanation was required to convince them that they were all good Americans, both under our laws and in fact’ (R.W. Parkhurst, ‘American Fleet in the Antipodes’, The Military Engineer, 17, no. 96 [1925]: 515).

Aboard many of the US battleships and cruisers were catapult-mounted seaplanes, unarmed types intended primarily for reconnaissance and gunnery spotting. The two most common aircraft were the Vought VE-7 and the recently introduced Vought UO-1, both biplane designs with a central float balanced by two outriggers towards the tips of the lower wings. These two Vought types shared the same mainplane and tailplane design, but where the VE-7 had a flat-sided fuselage, the UO-1 was more rounded in the vicinity of the cockpit and had a longer fixed fin. When appointed to a specific vessel, each aircraft featured the name of its host in large capital lettering on both sides of the fuselage, greatly assisting in identification of the parent warship. An individual aircraft number – 1, 2 or 3 – was added beneath the ship’s name.

During the US Fleet visit to Australia in 1925, UO-1s participated in exercises with Royal Australian Navy vessels, while six flew off their respective ships and landed beside the main Royal Australian Air Force base at Point Cook in Port Phillip Bay. One of USS OKLAHOMA’s UO-1s began to rapidly take on water after landing at Port Melbourne on 3 August 1925, requiring urgent recovery to avert complete loss of the aircraft (‘Seaplane in trouble at Port Melbourne’, Argus, 4 August 1925, p.20). Nevertheless, this type served the US Navy for a decade from 1923 until 1933. On 7 December 1941, USS OKLAHOMA was struck by multiple torpedoes and capsized when attacked by Japanese naval aircraft at Pearl Harbor. It was later salvaged but decommissioned in September 1944 as beyond economic repair, sinking en route while under tow to be scrapped in San Francisco in May 1947.SignificanceThe deployment by a major US Navy fleet to Sydney and Melbourne in 1925 comprised the largest visit to Australia by foreign warships between the 1908 US Great White Fleet and the arrival of the British Pacific Fleet in 1945. This spectacle of geostrategic posturing sent messages to Australia, Britain and Japan in the aftermath of the 1922 Washington Treaty and subsequent 1923 Four-Power Treaty, intended to limit a naval arms race in the Pacific Ocean. The interwar period was also a time of rapid technological evolution in naval warfare, particularly the role of aircraft for reconnaissance to extend the range of capital ships, alongside the strike and defensive capabilities that emerged with aircraft carriers. Capturing a Vought UO-1 seaplane on the rear deck of battleship USS OKLAHOMA (BB-37) during its time in Melbourne, this photograph encapsulates both American naval predominance in the 1920s and the US Navy’s focus on enhancing performance through new technology.September 1902

30 April 1949

Samuel J Hood Studio

July 1925

Samuel J Hood Studio

July 1925

Samuel J Hood Studio

July 1925