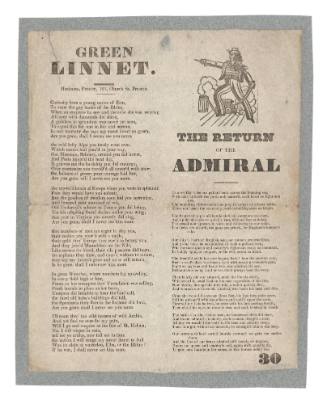

Broadsheet featuring the ballads 'The Sailor's Tear' and 'The Soldier's Tear'.

Date1828 - 1832

Object number00017370

NameBroadsheet

MediumWoodcut engraving and printed text on paper mounted on card.

DimensionsOverall: 257 x 189 mm, 0.015 kg

ClassificationsEphemera

Credit LineANMM Collection

DescriptionA broadsheet featuring the two ballads titled ' The Sailor's Tear' and 'The Soldier's Tear'.

Both ballads refer to the depature of men and their sadness at leaving loved ones behind.

The sheet was printed by T. Batchelar, Hackney Road, London.HistoryThe Sailor's Tear.

He leap’d into the boat

As it lay upon the Strand;

But oh! his heart was far away,

With friends upon the land,

He thought of those he love’d the best,

A wife, and infant dear, —

And feeling fill’d the Sailor’s breast,

The Sailor’s eye, — a tear.

They stood upon the far off cliff,

And wav’d a ‘kerchief white,

And gaz’d upon his gallant bark,

‘Till she was out of sight.

The Sailor cast a look behind

No longer saw them near,

Then rais’d the canvass to his eye,

And wiped away a tear.

Ere long o’er ocean’s blue expanse,

His sturdy bark had sped;

The gallant Sailor from her prow,

Descried a Sail a-head;

And then he rais’d his mighty arm,

For Britain’s foes were near,

Ay then he raised his arm, but not

To wipe away a tear.viii

The Soilder's Tear.

Upon the hill he stood,

To take a last fond look,

Of the spire and village church,

And the cottage on the brook.

Beside that cottage porch,

A girl was on her knees,

She held aloft a snowy scarf,

That fluttered in the breeze.

She breathed a prayer for him,

A prayer he could not hear,

But he paus'd to bless her, as she knelt,

And wip'd away a tear.

He turn'd him from the spot,

Oh, do not deem him weak,

For dauntless as the soldier was,

Yet a tear was on his cheek.

Rush, rush, to battle plains,

In victory's dark career,

Be sure the hand that bearest thee,

Has wip'd away a tear.

In the popular ballad "The Sailor’s Tear" (1835) the song-writer uses the sailor as the ideal manly Briton, melding feeling, domesticity, and fighting. The potential tensions of attaining apparently incompatible aspects of the manly man – being both a tender husband and father and a fighting man able to perform his duty to the nation – were resolved in this kind of imagery. The wife and infants and home were the sailor’s motivation to leave them: to defend and protect them. Thus he was in these three stanzas transformed from loving husband to the mighty foe of Britain’s enemies.

There is a similar poem/song by the same composer and poet called "The Soldier’s Tear" which follows this format. This fighting man leans upon his sword to wipe away a tear and takes his last look at a cottage in a valley, at whose door there is a ‘girl’. He is leaving his suitor rather than his family. In the final stanza the reader is asked ‘do not deem him weak/For dauntless was the Soldier’s heart,/Tho’ tears were on his cheek’. As these closing words hint, by the mid nineteenth century, tears were far less compatible with manliness and the stiff upper lip was arriving.

Broadsheets or broadsides, as they were also known, were originally used to communicate official or royal decrees. They were printed on one side of paper and became a popular medium of communication between the 16th and 19th centuries in Europe, particularly Britain. They were able to be printed quickly and cheaply and were widely distributed in public spaces including churches, taverns and town squares. Their function expanded as they became used as a medium to galvanise political debate, hold public meetings and advertise products or cultural events.

The cheap nature of the broadside and its wide accessibility meant that its intended audience were often literate individuals but from varying social standings. The illiterate may have also had access to this literature as many of the ballads were designed to be read aloud. In 'Popular Culture in Seventeenth-Century England', Peter Burke notes that the golden age of the broadside ballad, between 1600 and 1700, saw ballads produced at a penny each which was the same price for admission to the theatre.

The ballads also covered a wide range of subject matter such as witchcraft, epic war battles, murder and maritime themes and events. They were suitably dramatic and often entertaining, but as James Sharpe notes, also in 'Popular Culture in Seventeenth-Century England', some of them were designed as elaborate cautionary tales for those contemplating a life of crime.

The broadside ballads in the museum's collection were issued by a range of London printers and publishers for sale on the streets by hawkers. They convey, often comically, stories about love, death, shipwrecks, convicts and pirates. Each ballad communicates a sense that these stories were designed to be read aloud for all to enjoy, whether it was at the local tavern or a private residence.

SignificanceBroadsheets were designed as printed ephemera to be published and distributed rapidly. This also meant they were quickly disposed of with many of them not surviving the test of time. The museum's broadsheet collection is therefore a rare and valuable example of how maritime history was communicated to a wide audience, particularly in the 18th and 19th centuries. They vibrantly illustrate many of the themes and myths surrounding life at sea. Some of them also detail stories about transportation and migration.