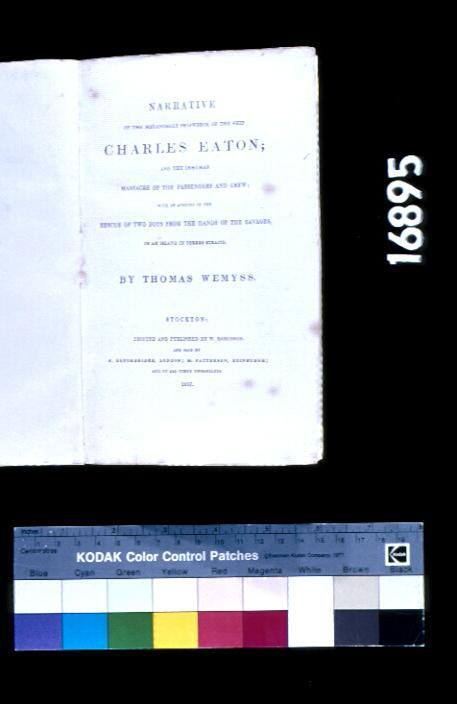

Narrative of the melancholy shipwreck of CHARLES EATON

Author

Thomas Wemyss

Publisher

W Robinson

Date1837

Object number00016895

NameBook

MediumInk on paper

DimensionsOverall: 200 x 125 mm, 0.05 kg

ClassificationsBooks and journals

Credit LineANMM Collection

DescriptionThe full title of this work by Thomas Wemyss gives an indication of the horrors that lie within - 'Narrative of the melancholy shipwreck of the ship CHARLES EATON: and the inhuman massacre of the passengers and crew: with an account of the rescue of two boys from the hands of the savages in an island in Torres Straits'. This work describes the rescue of two survivors from the shipwreck of the CHARLES EATON from Murray Island in 1836. All crew and passengers survived the inital shipwreck in the Great Barrier Reef but several of them were then murdered by inhabitants of the islands in the area. The author based part of the narrative on an account from a crew member of the rescue ship ISABELLA.HistoryCHARLES EATON, a barque of 313 tons, left Sydney for China via Torres Strait and Java in July 1834. It was carrying a cargo of calico and lead with 25 crew and six passengers. The ship ran into thick weather near the Charles Hardy Islands off Cape York and it was unable to avoid hitting a reef. CHARLES EATON was destroyed, one crew member drowned, and five other crew members managed to launch one of the boats and left the wreck. The remaining survivors spent the next week making a raft; however, once it was completed it was unable to hold everyone. It was tethered to what was left of the stern of the CHARLES EATON but the following morning the raft and occupants were not to be seen. It included a family, the D'oyly's, and the master of the ship. The remaining survivors, which included a cabin boy named John Ireland, spent another week making another raft. This raft moved slowly but after several days they arrived at a group of islands. The local inhabitants went out in canoes to the raft and the survivors chose to go with them back to the islands.

Once they arrived on shore, exhausted and weak, they searched for food but were unable to find any. The locals were gathered near them and the survivors felt threatened. However, as they were utterly exhausted, they lay down to sleep on the beach, resigned to their fate, and very soon after this they were attacked with most of them being murdered by a blow to the head. Ireland almost had his throat cut but fought against his attacker and escaped into the sea. However, he had no strength and returned to the shore where he was shot with an arrow to the chest but survived. Another member of the crew, Sexton, also struggled and survived. They witnessed the decapitation of bodies and the heads of the victims placed around a fire.

The next day Ireland and Sexton were taken to another island where they found the two young D'Oyly boys, George and William, and the ship's dog. William was approximately two or three years old. The boys told a similar story of the fate of the first raft. They stayed on the island with about 60 locals for two months, when the group split with one taking Ireland and William D'Oyly. This group travelled from island to island until Ireland and D'Oyly were traded for a bunch of bananas each. The boys were then taken to Murray Island, in the Torres Strait, and given new names; Ireland called 'Wak' and D'Oyly 'Uass'.

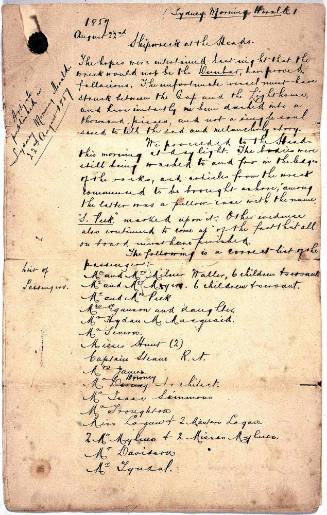

After about 13 months on an island in the Timor Sea, the five crew members from the boat of the CHARLES EATON reached Batavia and told authorities of the wreck and that passengers and crew had survived it. Also, in October 1835, the ship AUGUSTUS CAESAR had discovered some wreckage from the CHARLES EATON and informed the Admiralty upon arrival in England. The Governor of NSW, Sir Richard Bourke, was informed and he ordered HMCS ISABELLA to be fitted out to investigate the Torres Strait under the command of C M Lewis. ISABELLA left Sydney on 3 June 1836.

ISABELLA reached the Torres Strait and proceeded to search for survivors on a number of islands. It arrived at Murray Island on 19 June and a group of local inhabitants came to the ship to initiate trade. Lewis noticed a European boy on the shore of the island and encouraged the inhabitants to bring him to the ship. Ireland was taken to ISABELLA where he informed Lewis that William D'Oyly had also survived and was on the island. A series of negotiations took place between Lewis and the locals for them to hand over D'Oyly. They were reluctant and at one point Lewis made a demonstration of force but eventually D'Oyly was traded for axes and other implements. D'Oyly was upset at being separated from the women who had cared for him but was calmed with some clothing.

Lewis remained at Murray Island until 26 June, trading with the inhabitants and trying to uncover any information about the fate of George D'Oyly and Sexton. Ireland had heard that they had also been murdered after the groups had split and the inhabitants repeated this information to Lewis. On 18 July 1836 ISABELLA anchored at Darnley Island, also in the Torres Strait, where Lewis was told that the inhabitants had seen the heads of D'Oyly and Sexton on a nearby island. This island was reached on 25 July and the crew went ashore to search for any remains. The island was deserted but Lewis found a shed with many heads, including 17 European ones. There was evidence of the skulls being crushed by a blunt implement. The crew destroyed everything on the island and took the heads back to ISABELLA.

The ISABELLA returned to Sydney on 12 October 1836 having been away for 19 weeks. On 17 November 1836 the skulls were buried at the old Sydney Burial Ground but were moved to Bunnerong Cemetery near Botany when Central Station was built. William D'Oyly returned to England with Lewis in 1838 (surviving another near shipwreck on the voyage) and was raised by relatives. The fate of John Ireland is unknown.

SignificanceThis book is a rare account of the fate of the survivors of the shipwrecked CHARLES EATON. The death of the passengers and crew at the hands of island inhabitants shocked the colony of New South Wales.