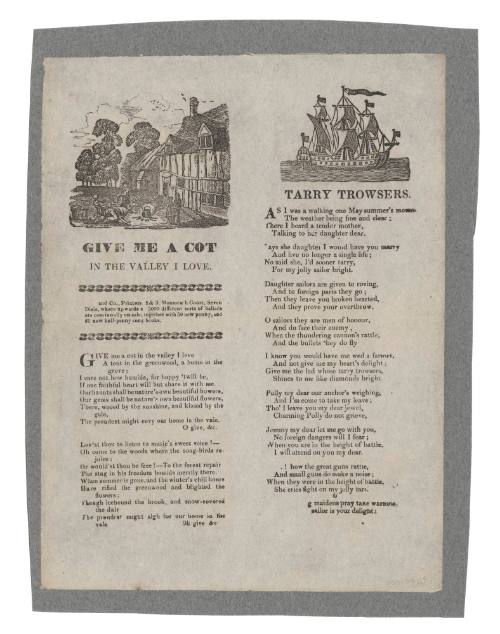

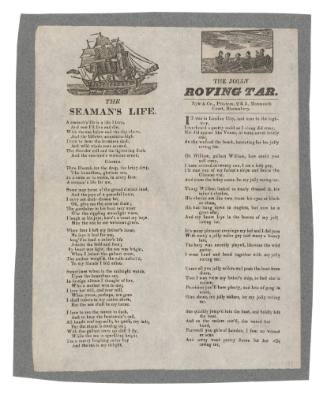

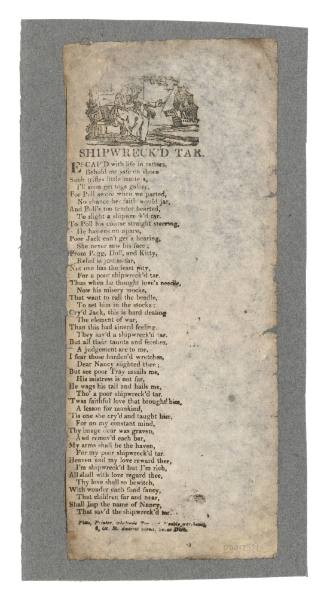

Broadsheet featuring the ballads 'Tarry Trowsers' and 'Give Me a Cot in the Valley I Love'.

Date1790 - c 1870

Object number00017404

NameBroadsheet

MediumWoodcut engraving and printed text on paper mounted on card.

DimensionsOverall: 255 x 190 mm, 0.022 kg

ClassificationsEphemera

Credit LineANMM Collection

DescriptionA broadsheet featuring the ballads 'Tarry Trowsers' and 'Give me a Cot in the Valley I love'. 'Tarry Trousers' refers to the sailor's practice of waterproofing their trousers with tar or the staining of their trousers from the tar on the ship's rigging. This may be among the reasons sailors were referred to as "tars," a term used since 1676. Between 1857 and 1891 sailors also wore black 'tarpaulin' hats (boater-shaped with ribbon around the crown). The term "Jack Tar" has been in use since the 1780s.

'Give me a cot in the valley I love' was by Steven Glover, a popular composer and arranger during the early - mid C19th.

HistoryTARRY TROUSERS.

As I was a walking one May summer's morning

The weather being fine and clear;

There I heard a tender mother,

Talking to her daughter dear.

Says she daughter, I would have you marry

And live no longer a single life;

No said she, I'd sooner tarry,

For my jolly sailor bright.

Daughter sailors given to roving,

And to foreign parts they go;

Then they leave you broken hearted,

And they prove your overthrow.

O sailors they are men of honour,

And do face their enemy,

When the thundering cannon's rattle,

And the bullets they do fly

I know you would have me wed a farmer,

And not give me my heart's delight;

Give me the lad whose tarry trowsers,

Shine to me like diamonds bright.

Polly my dear our anchor's weighing,

And I'm come to take my leave;

Tho' I leave you my dear jewel,

Charming Polly do not grieve,

Jemmy my dear let me go with you,

No foreign dangers I will fear;

When you are in the height of battle,

I will attend on you my dear.

Oh! how the great guns rattle,

And the small guns they do make a noise;

When they were in the height of battle,

She cries fight on my jolly tars.

GIVE ME A COT IN THE VALLEY I LOVE.

Give me a cot in the valley I love

A tent in the greenwood, a home in the grove;

I care not how humble, for happy 'twill be,

If one faithful heart will but share it with me.

Our haunts shall be nature's own beautiful bowers,

Our gems shall be nature's own beautiful flowers,

There, wooed by the sunshine, and kissed by the gale,

The proudest night envy our home in the vale.

O give, &c.

Lov'st thou listen to the music's sweet voice? ----

Oh come to the woods where the song-birds rejoice:

Or would'st thou be free?--To the forest repair

The stag in his freedom bounds merrily there.

When summer is gone, and the winter's chill hours

Have rifled the greenwood and blighted the flowers;

Though icebound the brook, and snow-covered the dale

The proudest might sigh for our home in the vale

O give &c.

"Mother-daughter dialogues on amorous themes make a common form of folk song from China to Peru, and they've been on the go since the priestesses of antiquity sang their instructive hymns to the little temple harlots. The present version, however, is probably less than two hundred years old. It was well-known from Yorkshire to Somerset, its circulation stimulated partly through its appearance on broadsides published by Catnach and others, but also doubtless by virtue of its fond and striking image of the sailor's trousers shining like diamonds in the young girl's eyes. Dickens knew the song, and he makes Captain Cuttle sing a scrap of it in Dombey and Son. (Lloyd, A.L, 'Lovely on the Water' LP, 1972).

Tarry Trousers.

As I was a walking one May summer's morning

The weather being fine and clear;

There I heard a tender mother,

Talking to her daughter dear.

Says she daughter, I would have you marry

And live no longer a single life;

No said she, I'd sooner tarry,

For my jolly sailor bright.

Daughter sailors given to roving,

And to foreign parts they go;

Then they leave you broken hearted,

And they prove your overthrow.

O sailors they are men of honour,

And do face their enemy,

When the thundering cannon's rattle,

And the bullets they do fly

I know you would have me wed a farmer,

And not give me my heart's delight;

Give me the lad whose tarry trowsers,

Shine to me like diamonds bright.

Polly my dear our anchor's weighing,

And I'm come to take my leave;

Tho' I leave you my dear jewel,

Charming Polly do not grieve,

Jemmy my dear let me go with you,

No foreign dangers I will fear;

When you are in the height of battle,

I will attend on you my dear.

Oh! how the great guns rattle,

And the small guns they do make a noise;

When they were in the height of battle,

She cries fight on my jolly tars.

Give Me A Cot in the Valley I Love.

Give me a cot in the valley I love

A tent in the greenwood, a home in the grove;

I care not how humble, for happy 'twill be,

If one faithful heart will but share it with me.

Our haunts shall be nature's own beautiful bowers,

Our gems shall be nature's own beautiful flowers,

There, wooed by the sunshine, and kissed by the gale,

The proudest night envy our home in the vale.

O give, &c.

Lov'st thou listen to the music's sweet voice? ----

Oh come to the woods where the song-birds rejoice:

Or would'st thou be free?--To the forest repair

The stag in his freedom bounds merrily there.

When summer is gone, and the winter's chill hours

Have rifled the greenwood and blighted the flowers;

Though icebound the brook, and snow-covered the dale

The proudest might sigh for our home in the vale

O give &c.

Broadsheets or broadsides, as they were also known, were originally used to communicate official or royal decrees. They were printed on one side of paper and became a popular medium of communication between the 16th and 19th centuries in Europe, particularly Britain. They were able to be printed quickly and cheaply and were widely distributed in public spaces including churches, taverns and town squares.

The cheap nature of the broadside and its wide accessibility meant that its intended audience were often literate individuals but from varying social standings. The illiterate may have also had access to this literature as many of the ballads were designed to be read aloud.

The ballads also covered a wide range of subject matter such as witchcraft, epic war battles, murder and maritime themes and events. They were suitably dramatic and often entertaining, but occasionally they were designed as elaborate cautionary tales for those contemplating a life of crime.

The broadside ballads in the museum's collection were issued by a range of London printers and publishers for sale on the streets by hawkers. They convey, often comically, stories about love, death, shipwrecks, convicts and pirates. Each ballad communicates a sense that these stories were designed to be read aloud for all to enjoy, whether it was at the local tavern or a private residence.

SignificanceBroadsheets were designed as printed ephemera to be published and distributed rapidly. This also meant they were quickly disposed of with many of them not surviving the test of time. The museum's broadsheet collection is therefore a rare and valuable example of how maritime history was communicated to a wide audience, particularly in the 18th and 19th centuries. They vibrantly illustrate many of the themes and myths surrounding life at sea. Some of them also detail stories about transportation and migration.

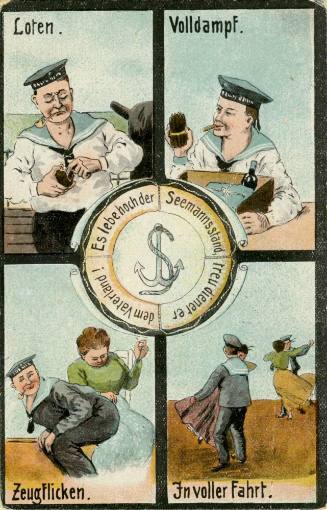

1901-1906

1914 - 1918

Ryle & Company

1845 - 1849

1950-1980

c 1910

3 February 1945

3 February 1945