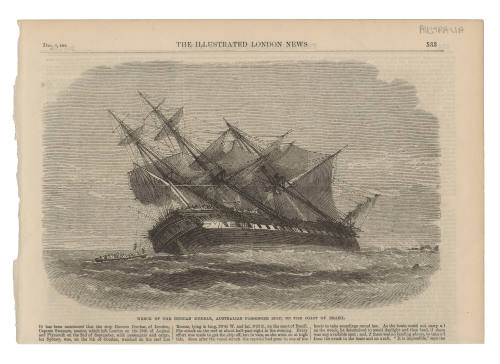

Wreck of the DUNCAN DUNBAR, Australian passenger ship, on the coast of Brazil

Publisher

Illustrated London News

(Established 1842)

Date1865

Object number00009096

NameEngraving

MediumPaper, ink

DimensionsOverall: 150 x 240 mm

ClassificationsEphemera

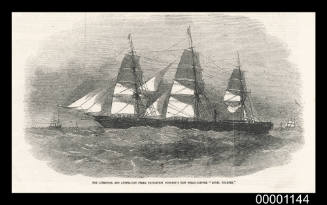

Credit LineANMM Collection

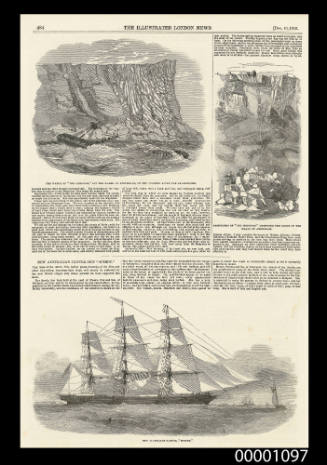

DescriptionThis is an image from The Illustrated London News of the DUNCAN DUNBAR, listing to port, and passengers being lowered by rope into a ship's boat. DUNCAN DUNBAR was a passenger ship operating between England and Australia, which ran aground at the Las Rocas shoals in the Atlantic Ocean in 1865.HistoryDUNCAN DUNBAR was built at Sunderland, Scotland, by James Laing & Sons in 1857. It was a wooden (teak and oak), three-masted clipper of 1,374 tons, owned by the well known English ship-owner Duncan Dunbar, who owned 24 ships, five of which were engaged in the emigrant trade to Australia.

Captained by James Banks Swanson, the DUNCAN DUNBAR was on a voyage between London and Sydney in 1865 when, driven by contrary winds, it struck the Rocas shoals in October 1865. The shoals are in the Atlantic Ocean some 150 miles northeast of Cape San Roque, Brazil. All 70 passengers and 47crew were rescued by the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company steamer ONEIDA.

The accompanying article is as follows:

It has been mentioned that the ship Duncan Dunbar, of London, Captain Swanson, master, which left London on the 28th of August and Plymouth on the 2nd of September, with passengers and cargo, for Sydney, was, on the 7th of October, wrecked on the reef Las Roccas, lying in long. 33.45W and lat. 3.52S on the coast of Brazil. She struck on the reef at about half-past eight in the evening. Every effort was made to get the ship off, but in vain, as she went on at high tide. Soon after the vessel struck the captain had gone in one of the boats to take soundings round her. As the boats could not carry all on the wreck, he determined to await daylight and then land, if there was any available spot; and, if there was no landing-place, to take all from the wreck in the boats and on a raft. "It is impossible," says one of the passengers, "to describe the state of mind in which we passed the hours of that most awful and trying night. The vessel was rolling from side to side, and striking most violently at each roll, in a way which seemed to threaten her instant destruction. As day dawned every glass was used in the hope of discovering some place uncovered by water, on which shelter, if only temporarily, might be taken. The captain again went in a boat, and succeeded in getting through the breakers to a landing-place on one of the two banks or islets of sand which rise about 7 ft above ordinary high-water mark. Preparations were at once made for landing. The passengers were lowered in a chair over the stern into the life-boats, it being impossible to get the boats alongside the rolling vessel. By seven we were all landed. On landing, we found that the little islet or bank of sand was covered with pig-weed, but there were no signs of water. During this day the captain directed the landing of water and provisions. Unfortunately, four out of five water-puncheons got at were lost, being stove in by debris of wreck, or having drifted away; and our anxiety was lest we should fail in procuring a supply of water for the party on the reef, consisting in all of 117 souls. For the first two days we had only half a pint of water apiece, although toiling in a severe and unaccustomed manner under a broiling sun, the thermometer being at 112. A tent was set up, and we sheltered ourselves as well we could. The place was much-infested by land-crabs and various kinds of vermin, as well as by sea-birds. We obtained provisions, however, from the wreck to such an extent that on our leaving the place, ten days afterwards, there remained water and stores sufficient to serve a hundred people for a hundred days. The Captain left on the fourth day, in the life-boat, for Pernambuco. After proceeding 120 miles he was picked up by the Hayara, American ship, and dropped fifteen miles from Pernambuco. There he procured the assistance of the Royal mail-ship Oneida, which immediately came to the island and took all hands, 116 in number (the captain having remained in Pernambuco), safely to Southhampton. The ladies behaved with wonderful bravery from first to last."

From the Sydney Morning Herald, 16 December 1865:

'The wreck of the Duncan Dunbar, which will be heard of with regret, has happily not been accompanied with any of that disastrous loss of life which made her semi-namesake so sadly famous. On the whole, accidents to outward bound ships to Australia have been few, and we trust they may remain so. The emigration to Australia has been far safer than that to America.'

From the Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser, 19 December 1865:

WRECK OF THE DUNCAN DUNBAR - We regret to learn by the latest English telegram received last evening that the fine ship Duncan Dunbar, bound to this port from London, was wrecked on the rocks off Pernambuco about the 8th Ootober. It is satisfactory to know that the passengers and crew were all, saved, and were being taken on by steamer to London. The following is a list of her cabin passengers : Mrs. Henry Mort, a Misses Mort, servant, and child; Mr. George Thornton and Son, Mrs. Thornton, Miss Thornton; Mr. and Mrs. Robinson, Mrs. and Miss Hudson, Mr. and Mrs Jones, child, and servant; Mr. and Mrs. Davis, child, and servant; Mrs. Davis; Mr. and Mrs. Christian, Mr. and Mrs. W. Christian, Mr. and Mrs. Holt, Mrs. Debenham, Miss Young, Mrs. Charles Haigh, Mr. Galloway, Mr. Parbury, Mr. Downy, and Mr. Crase.- Dec. 14

From The Brisbane Courier, 17 January 1866:

'The ship Duncan Dunbar has been wrecked on her passage from London to Sydney. No lives were lost. The Sydney Insurance Companies will lose £40,000 by the wreck.'

From The Sydney Morning Herald, 17 February 1866:

WRECK OF THE DUNCAN DUNBAR.

(From the Times, December 22)

The following correspondence has passed in reference to the loss of the above vessel -

"Board of Trade, Whitehall, December 21

" Sir,- With reference to your report on the wreck of the Duncan Dunbar, I am directed by the Board of Trade to inform you that they were so dissatisfied with some of the evidence that they thought it desirable to take the opinion of the Hydrographer to the Admiralty.

" I now enclose his report for your information, and I am to add that the professional officers of the Board of Trade entirely agree with the Hydrographer.

"His report states the facts of the case so fully, and points out the errors in the evidence of Captain Jasper Selwyn and Captain Trivett so distinctly, that it is un- necessary to enter at large upon these subjects in this letter.

" The Board of Trade have only to observe that the witnesses in question (upon whose testimony the conclusions of the Court seem to have been based) not only assume hypothetical currents (of the actual existence of which there is no evidence whatever), in order to account for a wreck which the course steered is quite sufficient to account for, but they pronounce and give credit to the opinion that a master of a first-class ship in the merchant service, when within two or three hours sail of a dangerous reef, and steering directly for it, is justified in neglecting the obvious precaution of taking an afternoon observation.

" The Board do not believe that such an opinion obtains among the intelligent officers of the mercantile marine; but if such an opinion were by means of the evidence in question to receive a credit which it does not now possess, the result of the inquiry would be to do serious harm and to increase the dangers of shipwreck.

" In order to prevent the evidence in question from having this effect the Board of Trade think it their duty to publish this letter and the enclosed report from the Hydrographer.

" I am, Sir, your obedient servant, T. H. Farrer,

" To JamesTraill, Esq., Police Court, Greenwich."

" December 16.

" ' In regard to the loss of the Duncan Dunbar on the Rocos Shoal, I have to remark that supposing the ship to have been in the position as stated in the evidence at noon - viz , latitude 2.56 S., longitude 33 11 W., and to have subsequently steered at stated, from S.W. half S. to S.W. by S., and gone at a speed of between seven and eight knots - moreover, to have experienced the usual westerly current, as shown on the Admiralty chart - then she should as nearly as possible have been on shore on Los Rocos, at the moment she was, and her grounding proved that her chronometers were in no appreciable degree in error, and that the current as shown on the chart, and stated in the Admiralty sailing directions, really did exist.

" It seems very improbable that the witnesses examined did not give the extreme westerly course made by the ship and the more so as it appears the log-book was altered some days after the wreck to give the ship a more westerly course than had been assigned to her at the time.

"As regards the evidence given by Captain Selwyn R N, and Captain Trivett, of the mercantile marine, to which the Board of Trade desire to draw special attention I have to observe that in regard to the southerly and easterly current described by the former officer as existing from sixteen to twenty miles N. E. of Los Rocos, there is no evidence whatever of such a current in the records of this department; but, on the contrary, all the documents bearing on the subject go to prove the existence of a westerly current. In the plans of Los Rocos made by Captain Parish, R N , in 1856, and by Captain Selwyn, in 1857, no current is mentioned, and in the remarks of the latter officer which accompanied his plan, he notices the fact of the shoals lying in the heart of a westerly current, but communicates no information in regard to the southerly and easterly current stated in his evidence to have been established by him.

" 'In regard to the remarkable difference in the latitude and longitude observed by Captain Selwyn, I have only to say that Lieutenant Lee, of the United States' navy, fixed the position of the shoal in 1852, that Captain Parish, R N., made a survey of it in 1856, and planted 100 cocoanut trees, and that Captain Selwyn again made a plan of it in the following year, and planted seven trees, three of which appear to have survived; that the observations of these three officers in regard to latitude agree within five seconds, and that the difference in their longitude amounts to two or three miles, which is no more than was to have been looked for in results obtained by ordinary ships of war not specially supplied with instruments for the purpose.

" 'With reference to the statements of Captain Selwyn and Captain Trivett, that they would have pursued the course adopted by the master of the Duncan Dunbar under similar circumstances, I am obliged to say that I entirely differ from them as to the prudence and safety of such a course, and it is, I think, a dangerous doctrine to disseminate that a shipmaster in charge of life and property is justified in abstaining from making all possible observations to ascertain his position when in the neighbourhood of danger.

" ' A single observation for longitude at 4 p m of the 7th October ought to have prevented the catastrophe which occurred only four hours later.

" ' In regard of the recommendations of Captain Selwyn, referred to in the letter from the Board of Trade, which I presume alludes to the desirability of the establishment of a lighthouse on the Rocos, I am of opinion that, however valuable such a light might be to the local trades, and admitting in an abstract point of view the utility of a light on any small low island in the middle of the ocean, it is not necessary for ocean ships, which would assuredly never adopt so westerly a route as the Rocos, unless compelled to do so, which would very rarely be the case.

" ' It is submitted that these observations should be referred for the information of the Board of Trade.

" ' Geo Henry Richards, Hydrographer.' "

From The Sydney Morning Herald, 19 January 1866:

WRECK OF THE DUNCAN DUNBAR,

(From our Melbourne Telegraphic Correspondent)

'The Duncan Dunbar sailed from Gravesend for Sydney on the 27th August, and was lost off Las Rocas, north of Pernambuco on the 7th of October. Her passengers and crew were all saved and conveyed by the Brazil mail steamer Oneida to Southampton, which place they reached on the 4th of November. The following is a list of her passengers: Mr. and Mrs. Robinson, Mr. and Mrs. Jones, child, and servant, Mrs. Mort and family, Mrs. and Miss Hudson, Mr. and Mrs. Davis, infant, and female servant, Mrs. Davis, Mr. and Mrs. Thornton, son, and daughter, Miss Young, Mr. and Mrs. William Christian, Mr. and Mrs. E. Christian, Mr. Wilkinson, Mrs. and Miss Beet, Mrs. Dudgeon, Mrs. Haigh, Messrs. Parbury, Galloway, Tomkins, Crase, Dowling, Hudson, Santylands, Geddes, thirteen second class passengers, and the officers and crew, fifty-nine in number.'

SignificanceThis work highlights the peril of emigrating and the realities of surviving a wreck. More than a million people emigrated to the Australian colonies in the 19th century - fewer than 4,000 lost their lives in shipwrecks.

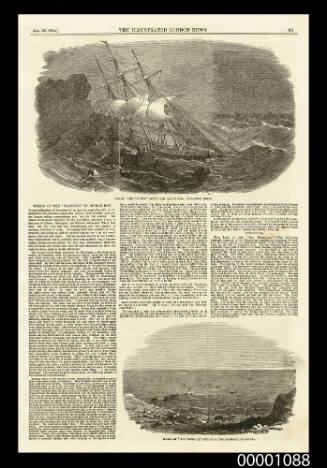

Illustrated London News

1855

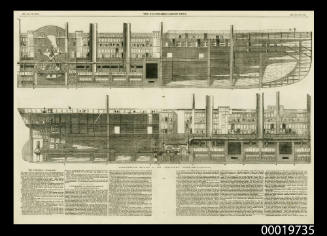

Illustrated London News

1887

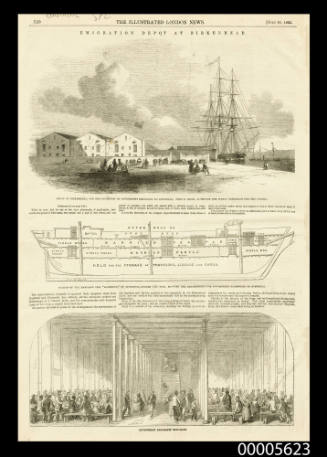

Illustrated London News

1855