Sketchbook of whaling scenes

Date19th century

Object number00004451

NamePainting sketchbook

MediumWatercolour on paper, ink on paper, pencil on paper, leather covered boards.

DimensionsOverall: 90 x 142 x 15 mm, 121 g

ClassificationsArt

Credit LineANMM Collection

Purchased with USA Bicentennial Gift funds

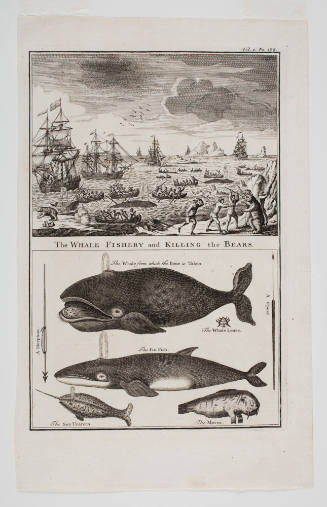

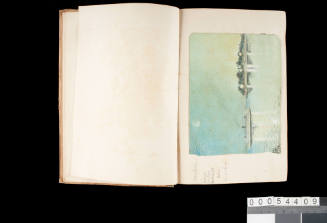

DescriptionThis sketchbook consists of 14 watercolours and five sketches of whaling scenes. The watercolours depict three-masted sailing ships on open seas and in arctic/antarctic whaling grounds, as well as a steam whaler, a shore processing station or fort, and illustrations of whalers in open boats using hand thrown harpoons and killing lances. The sketchbook also contains pencil sketches of harpoon designs, whalers and other men.

Although there are no inscriptions of places, a number of scenes could be Sydney Cove and one is showing the fortification of the harbour at Rio de Janiero.HistoryWhaling played an essential part in 19th century life. Industry and households depended on whale products for which there was little substitute. Whale oil was used for lighting and lubrication until 1860 when kerosene and petroleum started to gain popularity. The pure clean oil from sperm whales was a superior source of lighting and the finest candles were made from the whale's wax-like spermaceti. Sperm oil was the first cargo export of New South Wales, and it was not until 1833 that whale oil was surpassed in export value by the land based wool industry. Whale oil was also used in soaps, medicines and the manufacture of paints. Light and flexible, baleen - the bristle-fringed plates found in the jaws of baleen whales - had many uses in objects which today would be made out of plastic, including brushes, handles, and corsets.

From the 18th century, the ports of the Australian colonies were frequented by British and American whaling vessels where they outfitted their ships and recruited whalers on the doorstep of the fruitful whaling grounds of the Pacific. By the mid 19th century all of the cities of the Australian colonies were seaports, and Sydney and Hobart had developed into important whaling ports, with large populations of sperm whales off the coast.

Until the production and widespread use of harpoon guns, explosive harpoons and steam whaling vessels in the 1860s, whaling was an extraordinarily dangerous occupation which had remained virtually unchanged for centuries. Whales were hunted from long open boats rowed by men who were armed with hand-held harpoons and killing lances. The hand-thrown harpoon attached a rope to the whale which was fastened to the boat. The wounded whale would tow the boat and crew in an effort to rid itself of the painful harpoon. Each time the whale surfaced to breath it would be lanced by the headsman. Killing the whale was a dangerous and lengthy process, and once the whale was dead, the crew had to tow the whale to the ship or station for processing. The whaling barque HELEN was still using this method as late as 1899 operating out of Hobart.

No part of the whale was wasted in the modern whaling process. Teams of flensers started from the head and stripped the blubber and then hacked it into manageable blocks. Pressurised steam digesters separated the oil from the liquid product which was dried, ground into powder and sold as whale meal for animal feed. In the 19th century, great iron cauldrons called trypots were used at sea and on shore for the stinking, greasy job of boiling down whale blubber. Pairs of trypots surrounded by bricks were called the tryworks. The blubber was heated and stirred until the precious oil separated out. It was then ladled into large copper coolers and later poured into casks for storage and shipment.

SignificanceCarried out by an accomplished amateur artist, these images clearly document a specific whaling voyage to an arctic/antarctic whaling ground, and offer a first-hand look at the 19th century whaling industry, particularly the hunting methods and equipment employed.

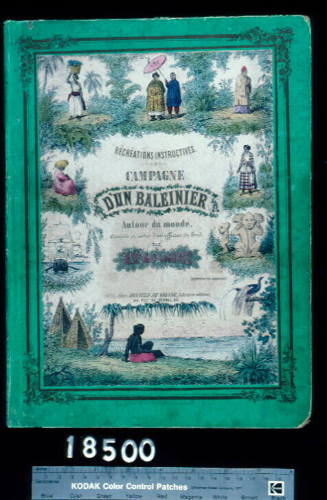

c 1850

Achille Saint-Aulaire

c 1845

19th century

![Untitled [Illustration from The Whalers]](/internal/media/dispatcher/129159/thumbnail)

![Untitled [Illustration from The Whalers]](/internal/media/dispatcher/129148/thumbnail)