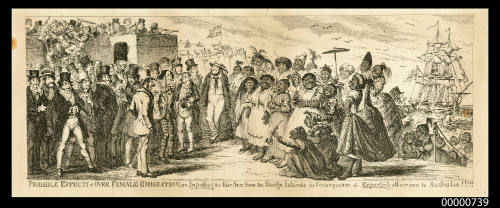

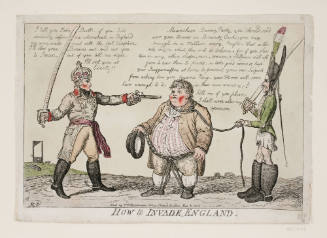

Probable effects of over female emigration, or importing the fair sex from the Savage Islands in consequence of exporting all our own to Australia.

Artist

George Cruikshank

(1792-1878)

Date1851

Object number00000739

NameEtching

MediumUncoloured etching on paper

DimensionsOverall: 178 x 422 mm

ClassificationsArt

Credit LineANMM Collection

DescriptionThis satirical etching on paper was designed and etched by the well-known British caricaturist, George Cruikshank. It depicts a group of British men facing a group of African women. It was published by David Bogue of 86 Fleet St London and is Cruikshank's response to the idea of the interbreeding of two different racial groups. A coloured example of the same etching appears in 'The Comic Almanac and Dairy for 1851', part of the ANMM Collection, number 00003817.

HistoryGeorge Cruikshank is one of the most famous British caricaturists and was active during a time where satirical prints were in high demand. Along with his contemporaries James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson, Cruikshank produced an array of social and political critiques in the form of colourful caricatures. Among the many themes he illustrated, the anti-abolitionist movement, British politics and patriotism featured most prominently.

The English novelist William Makepeace Thackeray wrote in admiration for the caricaturist in his work, 'An essay on the genius of George Cruikshank', (June, 1840). Thackeray claimed that a ‘greedy public’ ‘bought, borrowed or stole’ a ‘heap of personal kindnesses from George Cruikshank’ and therefore owed a great deal to the caricaturist. Among Thackeray’s many descriptions of Cruikshank there’s one which seems to stand out as particularly ironic. Labelled a ‘humble scraper on steel’, there is nothing modest or self-deprecating about the way that Cruikshank chooses to portray his subjects and themes. Characterised by whimsical and often grotesque individuals, his artworks demonstrate the power of exaggeration and sarcasm in communicating a political point.

Cruikshank’s works achieved great success and were published widely throughout his career. They were a medium through which attitudes and themes could be translated to the masses in a way that was easy to understand. As Thackeray notes in his essay, Cruikshank’s works were essentially an expression of popular culture:

'How we used to believe in them! to stray miles out of the way on holidays, in order to ponder for an hour before that delightful window in Sweeting's Alley! in walks through Fleet Street, to vanish abruptly down Fairburn's passage, and there make one at his "charming gratis" exhibition. There used to be a crowd round the window in those days, of grinning, good-natured mechanics, who spelt the songs, and spoke them out for the benefit of the company, and who received the points of humor with a general sympathizing roar. Where are these people now?'

According to Thackeray, despite Cruikshank's slight fall in popularity he had a ‘natural’ ability to connect with the ‘“little people”’ by creating art that imitated life. He noted that it took a degree of ‘honesty’ for Cruikshank to convey the messages featured in his caricatures and that he ‘would not for any bribe say what he did not think’. Yet despite his talent for telling ‘a thousand truths in as many strange and fascinating ways’, Cruikshank accepted a bribe of £100 from Kind George IV in 1820, ‘in consideration of a pledge not to caricature His Majesty in any immoral situation’.

During the 1840s, Cruikshank went on to become a passionate teetotaller, campaigning with the temperance and anti-smoking movements. He later developed palsy and died on 1 February 1878.

[Source: Nicole Cama, 'George Cruikshank: Satirising the Eastern trade', 5 June 2013, ANMM blog

SignificanceGeorge Cruikshank was one of Britain's most renowned and prolific caricaturists. His etching demonstrates the widespread fear and outlandish assumptions, which were caused by inherently xenophobic and racist attitudes and were commonly held during a time characterised by exploration and colonisation.

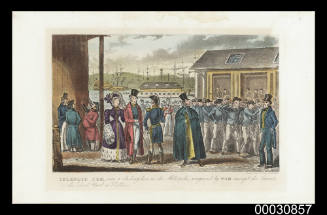

Percy Cruikshank

1850-1859