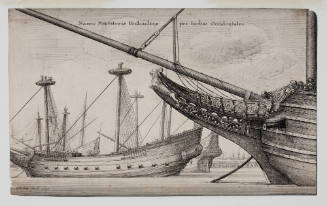

Naues Mercatoriae Hollandicae per Indias Occidentales

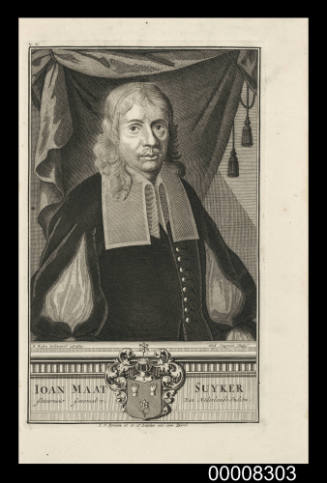

Maker

Wenceslaus Hollar

(Czechoslovakian, 1607 - 1677)

Date1647

Object number00001553

NameEngraving

MediumEngraving on paper

DimensionsOverall: 140 x 226 mm

ClassificationsArt

Credit LineANMM Collection Gift from Vaughan Evans

DescriptionEngraving by Wenceslao Hollar titled 'Naues Mercatoria Hollandicae per Indias Occidentales' ('Merchant ships in the West Indies Hollandicae') showing the Dutch merchant fleet for the West Indies at anchor.

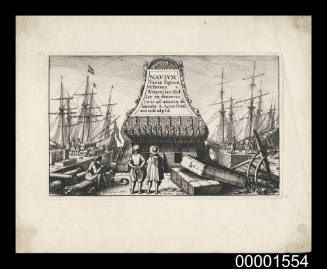

Plate from 'Navivm variae figurae et formae a Wenceslao Hollar in diuersis locis ad uiuum de linealae & aquaforti aeri insculptae' ('Navivn Various Shapes and Forms of Wenceslao Hollar in Various Places Living to the Lineal and Aquaforti Engraved Bronzes').

HistoryIn the 17th century the Netherlands was made up of seven fiercely independent provinces allied by war and religion (Calvinism) in the fight against the Catholic and Spanish-governed Southern Netherlands (present-day Belgium). The formation of the United Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC) in 1602 was a partnership of six cities from those provinces - Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Delft, Hoorn, Enkhuizen and Middelburg in Zeeland - each having a specified share of the costs and the profits, and representation on the central VOC board. Amsterdam was the largest chamber having fifty per cent of the shares.

The VOC was granted a monopoly by the Dutch government for lands east of the Cape of Good Hope and as far as the Straits of Magellan. A naval and military power in its own right, the VOC had the right to wage war with its private army, as well as to make treaties. The company grew rapidly, boasting 150 merchant ships, 40 warships, 50,000 employees, and a private army of 10,000 soldiers by the mid 17th century. The VOC became the world's most powerful trading company owing to its well-equipped ships, navigational expertise and a ruthless confidence in its right to trade, using force if necessary.

The VOC's trading posts ranged from the tiny Deshima (a former island at head of Nagasaki harbor, Japan) to the major fortified colonial settlement of Batavia (Jakarta) which the VOC conquered in 1619. The Company traded in spices from Indonesia and Timor, tea, silk and other textiles from India, metals from Japan and Malacca, as well as porcelain from China.

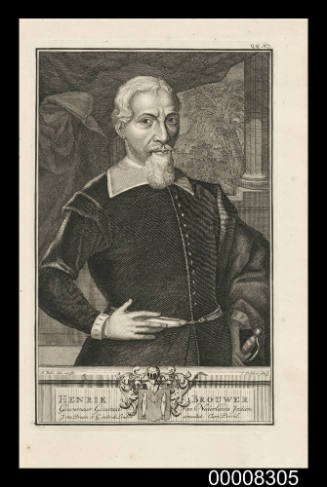

Other bases were set up, including a post at the Cape of Good Hope which secured the route from the Netherlands to the East Indies. In 1611, Hendrick Brouwer devised a route to the East Indies around the Cape of Good Hope, due east towards the west coast of Australia and then in an arc northwards to Java. This route took advantage of the Roaring 40s, and halved the time of the previous route established by the Portuguese. By 1617, Brouwer's Route was made compulsory for all VOC ships.

The VOC established a network of shipyards in the Dutch Republic which built trading ships of various sizes. The biggest of these ships, like the BATAVIA, were known as retourschips - or return ships - and were large enough to return from the East Indies to the Netherlands laden with cargo, soldiers and officials. Smaller vessels such as the DUYFKEN were designed to sail out to the East and trade throughout Asia, storing cargo at the VOC base at Batavia. Intent on the success of its ventures, the VOC demanded excellence from its shipwrights, sailors and captains. VOC ships and charts for this period were the most advanced in the world.

The VOC also explored south of the Spice Islands, in the hope of finding new commercial prospects. In 1606, Willem Janszoon commanding the DUYFKEN made the first recorded European landing in Australia. This marked the start of European charting, mapping and exploring of the land that became known as New Holland, and later Australia.

SignificanceWenzel Hollar was a prolific artist who executed a folio of Dutch shipping scenes from shipbuilding to the finished product. Most East Indiamen ships looked like men-of-war but they carried fewer guns and had a broader hull to store the valuable cargoes.

![Carte des Indes Orientale [Map of the East Indies]](/internal/media/dispatcher/238516/thumbnail)