Image Not Available

for Green Point Naval Boatyard

Green Point Naval Boatyard

Concrete Constructions Pty Ltd put in a proposal to the Naval Board to build 20 Fairmile craft from prefabricated parts, and the area chosen to site their works at Mortlake on the Parramatta River was a timber yard occupied by Allen Taylor and Company, just to the west of the still familiar Mortlake to Putney vehicular ferry. Negotiations to reach an agreed sale price were not successful and the Commonwealth Government then acquired the site using wartime emergency regulations. Adjacent land and jetties were leased from the Maritime Services Board of NSW and the entire area then leased to Concrete Constructions.

The site was occupied on 15 May 1942 and it was given the name Green Point Naval Boatyard. Construction of the first Fairmile ML 424 began in August 1942, and it was commissioned in late January 1943, almost five months later.

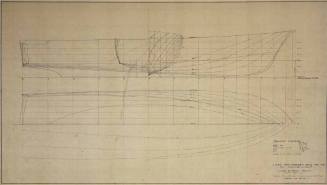

The yard consisted of a main building housing the various tradesmen and space needed to build and launch the wooden hulls, while adjacent to the wharf area were buildings and a large crane to do the engineering and machinery fitout while the craft were in the water. The main building contained a lofting floor, joinery workshop, timber storage to one side, an area for steaming timbers and six undercover slipways alongside each other.

The sheds and yard was set-up to run as a production line, the concept around which the English design for Fairmiles had been created. Many of the frames, bulkheads and other structural or joinery parts were designed to be made separately and off site in bulk, and then fitted to the hulls as they took shape. Groups of workers formed gangs that concentrated on one task only, moving along the slipways in succession doing their part on each hull. As one hull was finished and launched into the Parramatta River another could be started. The keel was laid and adzed into shape by four workers, who moved onto the next one, followed by the gang setting up the frames, then the next gang did the stringers, and so on through the process.

The arrangement for the Fairmiles was to build the first five craft from parts shipped out from Great Britain, originally to Singapore. However some of the vessels carrying these parts were sunk and only a portion of the material made it to Sydney. The missing items were then built onsite or at other factories, such as Ralph Symonds plywood firm who cut the bulkheads to shape before sending them down to Green Point to be finished off and readied for assembly. Eventually all the parts were made in this manner and a similar pattern was evolved for the GPVs.

This assembly line concept allowed the yard to operate with a small group of experienced shipwrights and marine tradesmen, overseeing a much larger group of other tradesmen from other fields and apprentices. Often the tradesmen were carpenters who knew the techniques but not the jargon and mysteries of ship building. Other workers were apprenticed straight from school. In this way the 20 Fairmiles for the Australian forces were completed at Green Point, with the last one ML 812 being commissioned in December 1943. Other Fairmiles were built for the US armed forces and known as Fast Supply Vessels. The GPVs were built once the Fairmile production run was completed.

The yard was run by Concrete Constructions manager Cecil Boden, a naval architect and graduate of Glasgow University. His small team of about eight shipwrights was divided up to head each gang as leading hands or foremen. The head shipwright was 'Darkie' Griffin, a well known boatbuilder from the Spit in Sydney. According to his son Joe, Darkie was taken from his position at Garden Island to set up the workforce and given free rein to chose the best shipwrights he could find to head the teams. George 'Micrometer' Evans was the lofting foreman, and the head draughtsmen on the site were Tommy Doyle, well known in the 18-foot skiffs. The remainder of the workforce numbered over five hundred, and despite their mixed skills and lack of boatbuilding experience, they were able to complete the 20 Fairmiles at an average time of just over four months, which was said to be better than any yard in England doing the same work.

After the war Concrete Constructions withdrew from the yard but manager Cecil Boden kept it operating under the name Green Point Shipbuilding and Engineering Company. They undertook a variety of projects including clinker lifeboats, sail training dinghies for the Navy, refits for cargo vessels and even built wooden car bodies. The yard closed around 1956.

Keith Lawrance ( Bundy No. 416) has strong memories of his time at Green Point. Living in Croydon, he went from school to work there as an apprentice starting in 1943. He worked in various sections including the lofting area where they laid out the full-size lines for the GPVs working from a plan drawn by Bert Swinfield. From the lines they created the patterns for the frames and other structure so they could be made up separately. He remembers the shipwrights including Joe Nash who came to work each day from Marylands with his horse and sulky , while another story said one of the workforce was in his 70s and used a walking stick to get around. The carpenters and other non-shipwrights were called dilute shipwrights. Many were very skilled woodworkers and Keith learnt a number of skills and tricks of the trade from them.

The gang working pattern had periods when members were left waiting before they could do their tasks. They filled their time in various ways such as playing cards in the bilge of an uncompleted hull, and a two-up school was run off to the side. However Keith recalls the day the plain-clothes police raided the site to put an end to the gambling. Workers scrambled over fences and fled as best they could, and the workforce went on strike until those who were caught were returned from the police lock-up to the site. Foreign orders were a consistent time filler as well, building items from the scrap timber. Keith still has small timber bowl and lid shaped from scrap plywood that had been bonded into a block. It was turned down on a makeshift lathe put together by workers using an electric drill fastened to a large scaffolding plank. Keith later used some off cuts to build a VJ class dinghy at home, a task encouraged by the staff to further his skills.

According to Joe Griffin, his father Darkie recalled that one fellow took things too far. He built plywood suitcases using some of the stock plywood, and it was soon noticed that plywood was missing from the stack. The culprit was caught taking the suitcases home stacked in different sizes with his own larger suitcase.

In 2009 the point is now called Wangal Centenary Bushland Reserve, with a combination of bushland, modern apartments and a wharf front in place of the factory sheds and wharves. Set in stone in the reserve is a plaque which commemorates the wartime effort that took place on the site.

Person TypeInstitution