Voyage to Disaster. The life of Francisco Pelsaert. Together with the full text of his journals…

Author

Henrietta Drake-Brockman

Publisher

Angus & Robertson

Printer

Halstead Press Pty Ltd

Date1963

Object number00042676

NameBook

MediumPaper, ink, cloth

Dimensions225 x 150 x 33 mm

ClassificationsBooks and journals

Credit LineANMM Collection

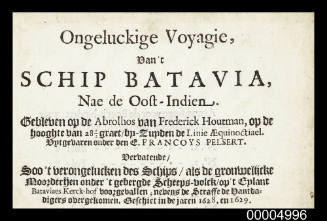

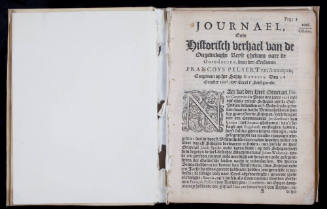

DescriptionHenrietta Drake-Brockman's book 'Voyage to Disaster: the Life of Francisco Pelsaert' explores the wrecking of VOC company ship BATAVIA off the coast of Western Australia in 1629, and the life of Francisco Pelsaert, including the full text of his journals translated by E D Drok.HistoryThe BATAVIA was built in 1628 for the Dutch East India Company (VOC) as a cargo ship. In October 1628, BATAVIA set sail for her maiden voyage from Texel, the Netherlands, for Batavia, Dutch East Indies (present day Jakarta, Indonesia) to collect a cargo of spices. For the trip out, she was carrying trade goods and chests of coins and was in a fleet of about seven vessels. In command was Francis Pelsaert, and Ariaen Jacobsz was skipper. These two men had a pre-existing acrimonious relationship, which deteriorated further as the voyage progressed. On board were approximately 332 crew, soldiers, and passengers. Jacobsz became friendly with a fellow crew member, Jeronimus Cornelisz, and the two plotted to take command of the ship by mutinying and turning to a life of piracy.

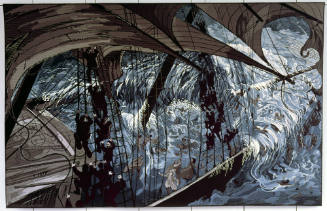

After calling at the Cape of Good Hope, Jacobsz steered BATAVIA off course and away from the rest of the fleet. He and Cornelisz had gathered a small group of men with similar views to mutiny, but just prior to their plan taking effect, BATAVIA hit a reef at Houtman Abrolhos, off the Western Australia coast on 4th June, 1629. The ship was unable to be re-floated and started breaking up. The crew and passengers were ferried to nearby islands using the ships two smaller boats, along with the water and food supplies. Some of the men drowned during this operation, but all the women and children reached land safely.

The islands on which they landed did not have available fresh water and Pelsaert organised a reconnaissance trip to the mainland to try to find a water supply. This proved unsuccessful and Pelsaert made the decision to try to reach Batavia in the long boat. Pelsaert, Jacobsz and 46 crew and some passengers reached Batavia on 7th July 1629, without loss of life. Jacobsz was promptly placed in prison due to his conduct on board BATAVIA.

Back on the island, Cornelisz took control of the remaining 268 survivors and weapons. Still dreaming of mutiny, he marooned 20 of the soldiers on a neighbouring island with the excuse of searching for a water source, and then proceeded to murder any of the remaining survivors who he perceived as a threat to his command or a burden on supplies. Eventually, Cornelisz and fellow mutineers murdered 125 men, women and children.

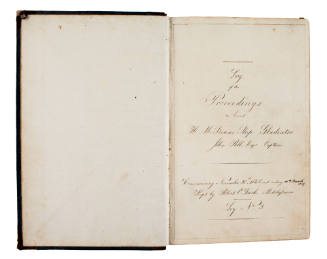

The soldiers, under the leadership of Wiebbe Hayes, had found a source of water and food on their island. They sent up smoke signals, as arranged with Cornelisz, which were ignored, and some of the survivors fleeing from the other islands reached the soldiers and told them of the mutiny and massacres. In anticipation of a confrontation, Hayes started making weapons out of debris of the BATAVIA, built a stone fort (still extant) and posted a watch. Cornelisz, realising his supplies were rapidly diminishing, decided to attack the soldiers. Several battles ensued and Hayes and his men captured Cornelisz. The mutineers regrouped under the command of Wouter Loos but their attack was interrupted by the return of commander Pelsaert in the SARDAM who quickly set about restoring order.

Pelsaert conducted a short trial and the leaders of the mutiny, including Cornelisz, were executed. Wouter Loos and a cabin boy were marooned on the Australian mainland as their crimes were not considered serious enough to warrant execution.

When SARDAM reached Batavia, Pelsaert was held responsible for the loss of the BATAVIA due to his lack of control and his assets were seized. He died a year later. Jacobsz never admitted to plotting the mutiny and was therefore spared execution due to lack of evidence. It is unknown what happened to him.

The shipwreck of the BATAVIA was formally identified in 1963 and is now protected under the Commonwealth Historic Shipwrecks Act 1976.

SignificanceHenrietta Drake-Brockman's research into the wrecking of the BATAVIA of the coast of Western Australia in 1629 and the publication of her research in the book 'Voyage to Disaster: the Life of Francisco Pelsaert’ (1963) was instrumental in the discovery of the wreck off Beacon Island in June 1963 by Dave Johnson and Max and Graeme Cramer. The subsequent discovery of the wreck and its associated survivor's camps led to the formation of the Western Australian Maritime Museum, the signing of the Australian Netherlands Committee on Old Dutch Shipwrecks Agreement (ANCODS) in 1972, and ultimately led to The Historic Shipwrecks Act (1976) the development of maritime archaeology programs in Australia.