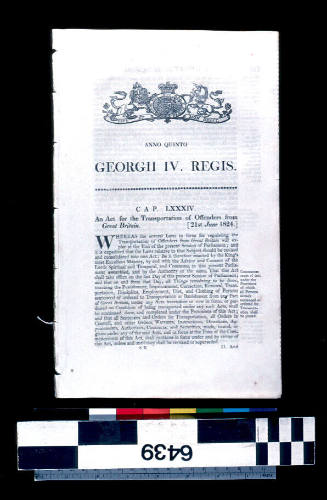

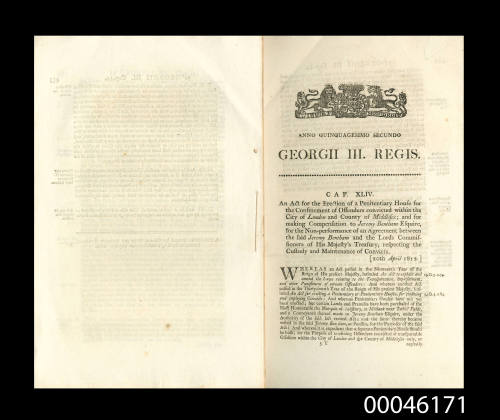

An Act for the Erection of a Penitentiary House for the Confinement of Offenders...

Date1812

Object number00046171

NameDocument

MediumPaper

DimensionsOverall: 321 x 200 x 2 mm

ClassificationsEphemera

Credit LineANMM Collection

DescriptionIn 1785 Jeremy Bentham, an English social critique and prison reformer, proposed the construction of the first modern penitentiary or Panoptican where prisoners would be under constant centralised observation. Bentham's work revolutionised prison design leading to the construction of England's first modern prison at Millbank in 1816.

HistoryIn the 21st century we are accustomed to thinking of imprisonment as one of the more obvious forms of punishment for convicted criminals. This was not so in the past. The industrial revolution, social change and war caused great changes in the lives of British people in the 17th and 18th centuries. Extreme poverty was a fact of life for many, and desperate people resorted to crimes such as theft, robbery and forgery in order to survive. If caught and convicted, they faced a harsh and complicated criminal code.

Until the early 19th century, except for the King's Bench, Marshalsea, Fleet Prisons and Newgate Gaol which were all Crown prisons attached to the central courts, prisons were administered locally and were not the responsibility or property of central government.

These prisons were used for the correction of vagrants, for those convicted of lesser offences, for the coercion of debtors and for the custody of those awaiting trial or the execution of sentence. Imprisonment was only one of a range of sentences that judges could inflict and, with no national prison system and few purpose-built prisons, it was often not their first choice. Instead, most criminal offences were punishable by death, public humiliation in the form of branding, whipping, hair cutting, the stocks or the pillory, the imposition of a fine, or transportation overseas to a penal colony.

From the late 16th century, transportation was mostly used as punishment for crimes against the state. Together with short term imprisonment, fines and capital punishment, it formed the cornerstone of the British criminal justice system. The introduction of the Transportation Act of 1718 effectively established transportation to the colonies as a punishment for crime and transportation became used as a large-scale criminal deterrent.

British courts sentenced criminals on conditional pardons or those on reprieved death sentences to transportation. Prisoners were committed under bond to ship masters who were responsible for the convict's passage overseas in exchange for selling their convict labour in the distant colony. Transportation became an increasingly common form of punishment during the 18th century; a solution that helped solve the overcrowding in British prisons and provided much needed labour for the American colonies of Virginia and Maryland.

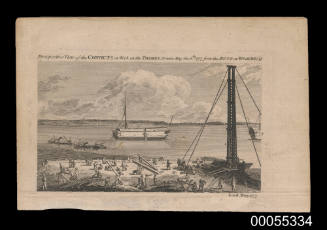

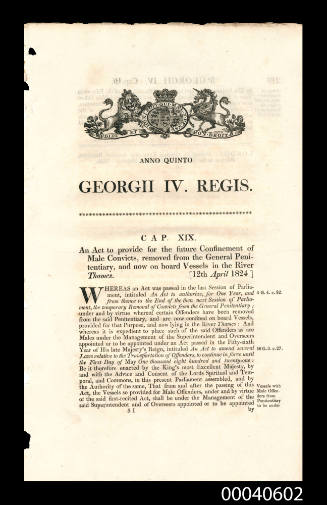

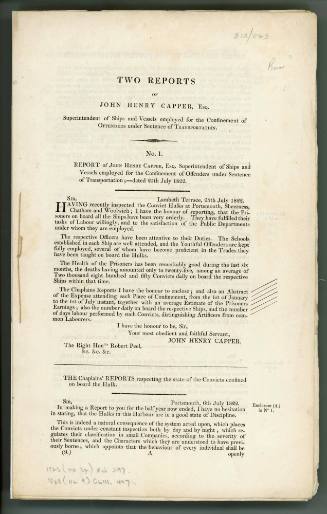

The loss of the American colonies in the War of Independence put an end to the mass export of British convicts to America. Many of the convicts in England's overcrowded jails were sent instead to the hulks (decommissioned naval ships) on the River Thames and at Portsmouth, Plymouth and Cork (Ireland) where they were employed in river cleaning, stone collecting, timber cutting and dockyard work. Although originally introduced as a temporary measure the hulks quickly became a cost-efficient, essential and integral part of the British prison system. The establishment of these hulks marked the first involvement of central government in the ownership and administration of prisons and they remained in operation until the mid-1880s.

In 1784, under the Transportation and Penitentiaries Act, felons and other offenders in the hulks could be exiled to colonies overseas which included Gibraltar, Bermuda and in 1788, the colony of NSW. (Frost, 1995) Between 1788 and 1868 over 160,000 men, women and children were transported to Australian colonies by the British and Irish Governments as punishment for criminal acts.

Jeremy Bentham (15 February 1748 - 6 June 1832) was an English jurist, philosopher, legal and social reformer, political radical, and a leading theorist in Anglo-American philosophy of law.

Bentham was a great advocate for utilitarianism - a universal body of law that would cause "the greatest good for the greatest number of people", also known as "the greatest happiness principle". Bentham also argued in favour of individual and economic freedom, the separation of church and state, freedom of expression, equal rights for women, the end of slavery, the abolition of physical punishment (including that of children), the right to divorce, free trade, usury, and the decriminalisation of homosexual acts. He criticised the death penalty, was one of the founders of University College London, the first English university to admit all, regardless of race, religion or political belief, and is probably best known in popular society as the originator of the concept of the Panopticon.

Among his many proposals for legal and social reform was a design for a prison building he called the Panopticon. Twentieth-century French philosopher Michel Foucault argued that the Panopticon was paradigmatic of a whole raft of 19th-century disciplinary institutions and although it was never built, in its pure form, the idea had an important influence upon later generations of prison designers and reformers and many prisons in Europe, America and Australia were influenced by Bentham's proposed design including the Palacio de Lecumberri in Mexico, Port Arthur in Van Diemen's land, the Round House in Fremantle, Western Australia, Pentonville Prison in North London, Armagh Gaol in Northern Ireland, and Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia

The Panopticon was a purpose built, circular prison, with a central observation tower, based on the plan of a French military school in Paris which had been designed by Jeremy Bentham's brother Samuel Bentham. Jeremy Bentham's 1785 proposal allowed a central observer or warden to observe (-opticon) all (pan-) prisoners without the prisoners being able to tell whether they are being watched, thereby conveying what one architect has called the "sentiment of an invisible omniscience." Bentham supplemented this principle of constant observation with the idea of contract management that would have a pecuniary interest in lowering the average rate of mortality, reform through hard work such as on a treadmill, making bricks, making brooms, washing clothes etc,

Bentham devoted a large part of his time and almost his whole fortune to promote the construction of a prison based on his scheme. After many years and innumerable political and financial difficulties, he eventually obtained a favourable sanction from Parliament for the purchase of a place to erect the prison, but in 1811 after the King refused to authorise the purchase of the land, the project was aborted.

In 1812 the Act for the Erection of a Penitentiary House for the confinement of offenders convicted of transportable offences was passed in Parliament. In 1813 Bentham was awarded a sum of £23,000 in compensation for his monetary loss. Millbank Prison, the first modern prison in England, on the present day site of the Tate Modern in London, was built in 1816 using many of the principles put forward by Bentham in his work on the Panopticon.

It was the development of the modern prison or penitentiary based on some of the principle of Bentham's Panopticon along with changes in the criminal justice system and opposition from Australian colonists that eventually led to the abandonment of the convict transportation system.

SignificanceThe development of purpose built prisons, as proposed by Bentham and the ACT FOR THE ERECTION OF A PENITENTIARY..., eventually led to the construction of Millbank Prison in London in 1816, the development of the modern prison system, and the cessation of convict transportation to Australia in 1868.

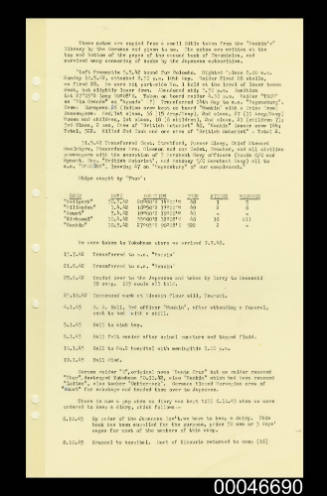

![Pontons Anglais [English prison hulks]](/internal/media/dispatcher/10232/thumbnail)