Convict brick and mould

Date18th century

Object numberV00040674

NameBrick and mould

MediumEarthenware, iron, timber

DimensionsOverall: 80 x 140 x 265 mm

ClassificationsTools and equipment

Credit LineANMM Collection

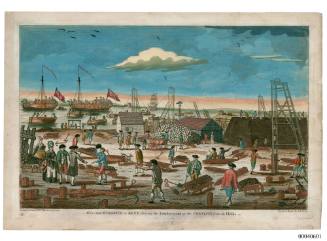

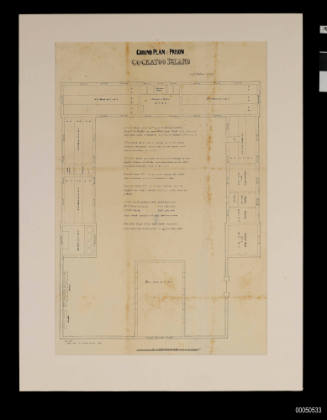

DescriptionBrick making was an essential industry in convict Sydney. Brick moulds such as this were use to hand-mould wet clay into brick ready for firing. A good supply of clay was located near Cockle Bay and at Brickfield Hill (present day Surry Hills), and convicts were put to work making bricks. The work was very hard and the most intractable convicts were sent to the Brickfields as punishment.HistoryAmong the First Fleet's cargo were 5,000 bricks and brick moulds, wooden boxes used to hand-mould wet clay into bricks ready for firing and a convict master brick-maker. A good supply of clay was located in March 1788 on what became known as Brickfield Hill (present day Surry Hills) and convicts were put to work making bricks. The work was very hard and the colony's most intractable convicts were sent to the Brickfields as punishment.

Between 30,000 and 40,000 bricks and tiles a month were expected from each brick establishment. There were five steps to making a brick: winning (mining) the clay, preparation, moulding, drying and burning (firing). In the pre-industrial settlement, all work had to be undertaken by hand. The best bricks produced were used for the outer walls of buildings, while the most damaged or least structurally sound were used for garden walls or paths.

In Australia, the majority of bricks manufactured by convicts were imprinted with a Broad Arrow or Board of Ordnance Mark. This mark or arrow marked the brick as government property decreasing the opportunity for theft. The Board of Ordnance was incorporated into the British War Office in 1855 as the Department of the Master-General of the Ordnance; and the Board of Ordnance and its mark was effectively abolished.

Extreme poverty was a fact of life for many in 18th and 19th century British society. In desperation, many resorted to crimes such as theft, prostitution, robbery with violence and forging coins as the means to survive in a society without any social welfare system or safety net. This was countered by the development of a complicated criminal and punishment code aimed at protecting private property. Punishment was harsh with even minor crimes, such as stealing goods worth more than one shilling, cutting down a tree in an orchard, stealing livestock or forming a workers union, attracting the extreme penalty of 'death by hanging'.

From the late 16th century, transportation was mostly used as punishment for crimes against the state. Together with imprisonment and capital punishment, it formed the cornerstone of the British criminal justice system. With the introduction of the Transportation Act of 1718 to combat a perceived increase in crime, transportation became used as a large-scale criminal deterrent.

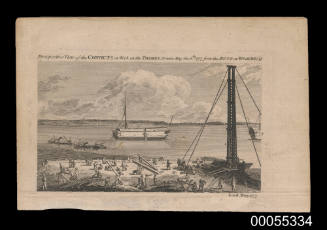

The loss of the American colonies in the War of Independence put an end to the mass export of British convicts to America. Many of the convicts in England's overcrowded jails were sent instead to the hulks (de-commissioned naval ships) on the River Thames and at Portsmouth, Plymouth and Cork (Ireland) where they were employed on river cleaning, stone collecting, timber cutting and dockyard work.

In 1784, under the Transportation and Penitentiaries Act, felons and other offenders were exiled to colonies overseas which included Gibraltar, Bermuda and in 1788, the colony of NSW.

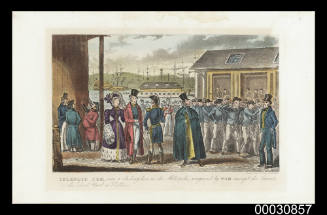

In January 1788 just over 700 convicts and their guards arrived at Port Jackson to establish one of the most isolated European colonies in the world. Over the next 80 years a further 160,000 convicts were transported from England to various parts of Australia to found or work in penal settlements that have become bywords for crime, pain and punishment.

SignificanceThis convict brick and mould is a symbol of Australia's convict past and the valuable work performed by the convicts in Australian colonial society. Convict potters, stonemasons and metal workers provided the skills for ambitious government building programs after the European occupation of Australia in the 18th century.Brickmaking work indicates changing attitudes among prison and convict establishment superintendents of the need to provide work as a method of reforming the criminal class.

18th century

1788-1840

1788-1840