The Daily Mirror - Captain Scott's Tomb near the South Pole

Publisher

Daily Mirror

Date21 May 1913

Object number00026012

NameNewspaper

MediumInk on paper

DimensionsOverall: 395 x 305 mm, 111 g

ClassificationsEphemera

Credit LineANMM Collection

DescriptionThis first edition of the special Scott memorial issues was one of the best selling pre-war issues of The Daily Mirror. It was published three months after news of his death had reached the United Kingdom. The newspaper contained photographs never published before along with excerpts from letters written by Scott in his final hours. The paper stated 'the photographs were the most remarkable, in their tragic interest, which have ever been published' and recorded 'one of the most splendid, the most inspiring tragedies in the world's history'. The letters were written as appeals to the British public to look after the welfare of the expedition's widows and survivors. These appeals resulting in large donations from the public covered the cost of the expedition, provided annuities for the widows and survivors and were used to form the Scott Polar Research Institute.

HistoryFor centuries philosophers and geographers theorised that there had to be a great continent in the south to balance the lands of the Northern Hemisphere. Aristotle called it 'Antarktikos'. Ptolemy called it Terra Australis Incognita' - the unknown southern land.

The search for the great landmass at the bottom of the world really began in the early 18th century. In 1773 Captain James Cook was the first to cross the Antarctic Circle but it wasn't until 1820 that the elusive Antarctic continent was finally seen, probably by English sealer Edward Bransfield. For the next 75 years explorers, sealers and whalers gradually pushed their way through the outlying islands and surrounding ice towards the continent.

The first to set foot on the white continent was Norwegian Henryk Bull, landing at Cape Adare on 24 January 1895 while hunting for new sealing and whaling grounds. Following this the continent was visited by a series of national expeditions which sailed in search of profitable whaling and sealing grounds and of geological marvels and scientific knowledge. Many sought to be the first to find the South Pole. The heroic age of Antarctic exploration was imminent.

For Britain it was a matter of national pride to be first to reach the South Pole. In July 1901 a British Antarctic expedition (1901-1904) sailed under the command of Robert Falcon Scott to march into the icy continent's heart. Just 660 kilometres from the Pole he had to turn back due to illness and insufficient supplies. On 30 July 1907 another British Polar hopeful and rival, Ernest Shackleton, set sail for Antarctic where he and his men reached a point just 156 kilometres from the Pole. This NIMROD expedition (1907-1909) achieved significant Antarctic 'firsts' including the ascent of Mount Erebus and locating the South Magnetic Pole.

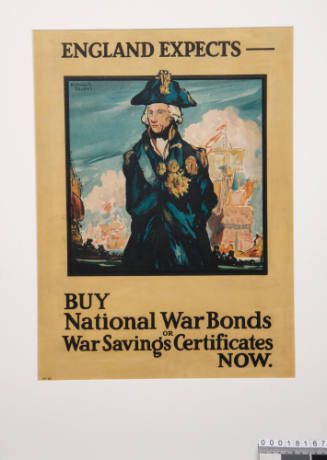

Scott's new expedition (1910-1913) aimed 'to reach the South pole for the Empire'. He received news that the professional Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen was also heading to Antarctica. The race for the Pole had begun. Scott, accompanied by Wilson, Oates, Evans and Bowers, reached the Pole on 17 January 1912 only to discover that Amundsen had beaten them. Robbed of the prize, morale was low and all five perished on the return leg. Scott was later accused of poor logistical planning, including his refusal to take dogs, but he also encountered unseasonably cruel weather. The bodies of Scott and his companions were discovered by a search party on 12 November 1912 and their records retrieved. Their final camp became their tomb; a high cairn of snow was erected over it, topped by a roughly fashioned cross. Scott had raised money for the expedition through various fundraising means such as lectures, sponsorship and private donations. The Daily Mirror had negotiated exclusive rights to Herbert Ponting's photographs with Scott prior to his departure for the expedition in 1910. Following the tragedy, Captain Robert Scott was hailed as a hero in the United Kingdom. Many memorials were erected in his honour throughout the country.

In the centenary of the expedition, it is noted that Scott's expedition was a scientific success with exceptional meteorological records and mineral and plant specimens still being studied and made use of a hundred years on.

Norwegian Roald Amundsen's team (1910-1912) was designed for a rapid ski and dog onslaught on the Pole. On 20 October he set out with 52 dogs and four men, Hanssen, Hassel, Bjaaland and Wisting. They set a quick pace and reached the South Pole, planting the Norwegian flag on 14 December 1911.

In December 1911, the Australia Douglas Mawson departed Hobart to undertake Australia's first expedition known as the Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1912-1913). Mawson had been a member of Shackleton's 1907 expedition and was determined to return to the South Pole and explore the coast to the west of Cape Adare, due south of Australia. Mawson set up two Antarctic exploring bases, one on Shackleton Ice Shelf under Frank Wild and the main base under his leadership at Cape Denison in Commonwealth Bay, south of Tasmania. At each base he and his men undertook a series of scientific investigations, including intensive land exploration along the coast and into the hinterland. On Mawson's return to Adelaide, he was treated as a hero and his great achievement as an Antarctic leader and scientist were later recognised with a knighthood. Mawson returned to the Antarctic twice more, in 1929 and 1931, as leader of the first and second British, Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expeditions (BANZARE).

SignificanceThis special edition of The Daily Mirror is significant in recording the media response to Robert Falcon Scott's British Antarctic Expedition in the TERRA NOVA during which Captain Robert Falcon Scott, Edward Adrian Wilson, Lieutenant H R Bowers, Captain Oates and Petty Officer Evans tragically lost their lives. The inclusion of never before published photographs of their final resting place, along with their surviving family members provides the reader with detailed information about the expedition and shows the human face of the tragedy.

Arthur Lederer

7 November 1938