Scrapbook regarding the Japanese submarine attack on Sydney Harbour

Datec 1942

Object number00029811

NameScrapbook

MediumInk on paper, cardboard, silver gelatin prints

DimensionsOverall: 320 x 247 mm, 0.5 kg

Display Dimensions: 317 x 470 x 90 mm

ClassificationsEphemera

Credit LineANMM Collection Gift from R G Sutherland

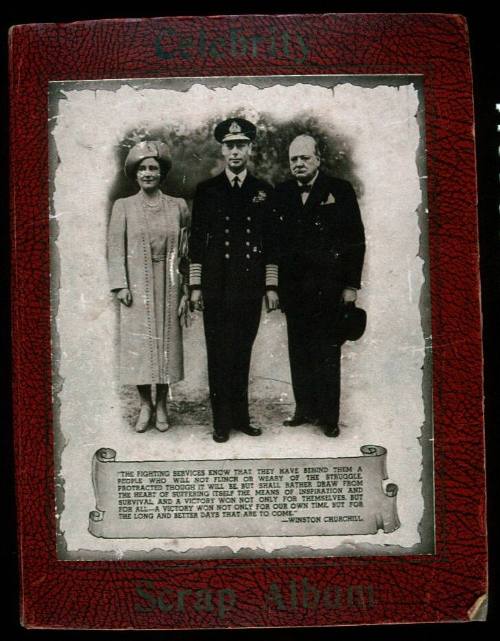

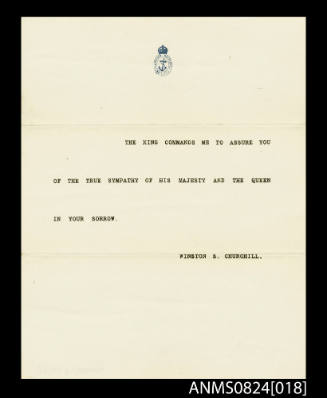

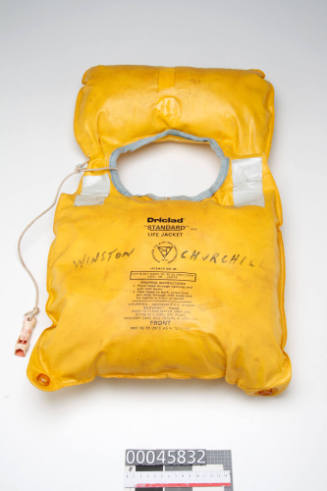

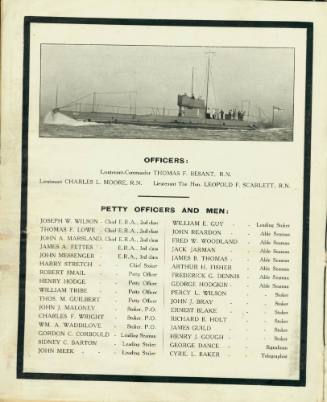

DescriptionA scrapbook, compiled by Mrs E G Sutherland (nee Hayes), nanny to Rear-Admiral G Muirhead-Gould's three sons, highlighting the events that surrounded the Japanese midget submarine attack on Sydney Harbour in May 1942. On the front cover is attached a photograph of Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon (the Queen Mother), her husband, George VI and Winston Churchill. There is a quote by Churchill on a scroll beneath reading "The fighting people know that they have behind them a people who will not flinch or weary of the struggle protraced though it will be, but shall rather draw from the heart of suffering itself the means of inspiration and survival and a victory won not only for themselves, but for all - a victory won not only for their own time, but for the long and better days that are to come. - Winston Churchill"HistoryThe Japanese Special Attack Group of two aircraft - carrying submarines and three with midget submarines was about to strike an unsuspecting Sydney. On 16 May the Russian steamer Wellen had been attacked some 30 miles east of Newcastle. Rear-Admiral Gerald Muirhead-Gould, in charge of harbour defences, suspended merchant sailing for 24 hours but patrols found nothing. A reconnaissance flight by a submarine-launched Japanese aircraft on 20 May was not detected. In the early hours of May 30th many military targets in the Harbour were noted from a Glen-type float-plane piloted by SusumuIto.The plane had been seen from Garden Island but was not identified as Japanese. On its return it capsized in heavy seas on landing, but the two crew were rescued by the parent submarine.

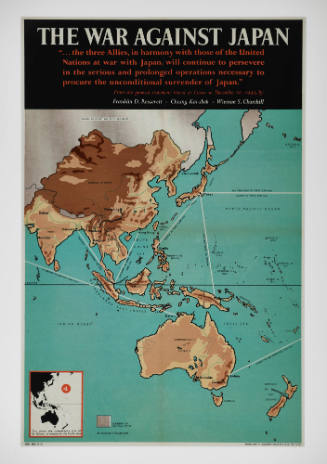

Australian defence authorities were aware of the vulnerability of the country's waterways.

In Sydney a boom net from Georges Head at Middle Head to Green Point on Inner South Head was begun in 1942, consisting of steel anti-torpedo mesh net supported by dolphins or piers.The gate to allow vessels through was supported by floating buoys and opened to shipping by a boom gate vessel which pulled the net across. By May the centre portion of the boom net had been built while gaps at the western and eastern ends were still to be completed.

Magnetic loop cables were laid across the harbour floor. Vessels that passed over them were registered and this information was compared with sightings and scheduled vessel movements to show up unauthorised craft .

After Pearl Harbour several modifications had been made to the two-man A-type midget submarines, including

an improved gyro compass, serrated net-cutters on bow and conning tower, a sled-like bow guard to help slide over

obstacles and a propeller guard to prevent entanglement in nets or cables.The submarines were 23.9 metres in length

with a diameter of 1.8 5 metres, weighed 46.2 tonnes and lacked any space for the most basic crew amenities. Each

one contained 208 batteries,72 in the bow section and 136 in the stern.They could stay submerged for 12 hours with a

maximum speed of 19 knots. Compressed air bottles were carried for blowing ballast tanks and launching the 45cm

kerosene motor powered torpedoes weighing 950 kilos each, while a sliding lead weight helped adjust boat trim. They were fitted with a periscope, two - way radio and demolition charges for self-destruction.

At dusk that Sunday evening 31 May, 1942, the parent submarines I22, I24 and I27, silently released their lethal cargo 12 km east of the Heads of Sydney Harbour.

The Japanese had chosen a full moon to aid their enterprise but clouds obscured it for some of that fateful night.The order of events was jumbled and chaotic although mechanical recordings and reports supplied a clearer picture later.The signature of an inward crossing was recorded on the indicator loop at 8.00pm but its significance was not recognised.The first report was of midget submarine No14, commanded by Lt Kenshi Chuma, sighted by Maritime Services Board watchman, James Cargill. It was snared at the western end of the boom net. Naval Auxiliary Patrol vessel LOLITA attacked with depth charges but they failed to explode, having been set for deeper water. It was not until 10.27 pm that the official warning was given, instructing all ships in Sydney Harbour to take anti-submarine precautions. Minutes later the crew of midget No14 unable to disentangle their sub from theboom net, blew up their vessel and themselves.

Meanwhile, another midget submarine, Midget A, commanded by Sub- Lt Katsuhisa Ban, had entered the harbour in the wake of a Manly ferry.The cruiser USS CHICAGO, moored off Garden Island, recently repaired at Cockatoo Island after its return from the Battle of the Coral Sea, sighted Ban's submarine and opened fire. The corvette

HMAS GEELONG was ordered to fire but waited until a Manly Ferry had passed before beginning its attack. Ferries

were kept operating because Rear Admiral Muirhead-Gould felt that more boats would 'keep the subs down till

daylight'. The Manly ferry passengers had a front row seat and according to one person 'bullets were streaking like

shooting stars'. It now seems remarkable that there was no serious 'collateral damage' from 'friendly fire', in today's

military terminology.

At 11.14 pm the order was given for "all ships to be darkened". No one knew how many submarines were in the

Harbour, air raid sirens sounded and some Sydneysiders thought a naval exercise was taking place.Then at about

12.20 am an enormous explosion rocked the Harbour. Ban's submarine had fired its torpedoes at the prize larget, USS CHICAGO. Both missed, but one hit the wall at Garden Island and the explosion lifted the accommodation vessel HMAS KUTTABUL, an old harbour ferry, out of the water. lt was blown to pieces and sunk, and 21 sailors died.This submarine was never recovered. It may have sunk off shore from damage sustained in the Harbour defence, or may have run down its batteries before reaching the parent sub.

The third midget submarine. No2, commanded by Lt Kei Matsuo, had been sighted at the Heads by Naval

Auxiliary Patrol boat LAURIONA, a large ketch-rigged motor sailer owned by the biscuit manufacturer Harold Arnott.

Around 11.00 pm another Harbour defence vessel, HMAS YANDRA, tried to ram No21 and then dropped six depth

charges, now set to detonate in the shallow water of the Harbour. At 3.00 am in the morning HMAS SEA MIST

sighted a submarine off Taylors Bay. Following its first depth charge, the crippled submarine rose to the surface and

sunk again.When recovered its propellers were still turning slowly.The crew had shot themselves.

Throughout the week newspapers carried the story of the difficult and dangerous salvage operation, with live, armed

torpedoes wedged in the tubes of sub No21. Damage to its relatively flimsy bow guard had prevented the torpedoes

from leaving their tubes on firing.

The naval funeral for the four Japanese submariners, and the return of their ashes to Japan with the repatriated

Japanese Legation, caused consternation among the public. In a radio broadcast in July 1942 Rear-Admiral Muirhead Gould defended his decision to honourably cremate the remains."Should we not accord full honours to such brave men as these,'' he asked. "It takes courage of the highest order to go out in a thing like that steel coffin."

The submarine was taken around the south-eastern states by road on a fund-raising tour and as a symbol of the Japanese attack, enabling people to see for themselves the confined spaces in which the submariners had to work, llive for a while, and then to die.

The professionals who examined the vessel for intelligence purposes were impressed at the quality of Japanese engineering, although its equipment also included British-manufactured valve gear acquired before the war.

The Japanese storage battery technology for example, was considered to be a advanced and the engineering standards of the propeller gear was singled out for favourable comment.

Nonetheless,several design features contributed to the poor rate of success of the raid.The submarines appeared to

experience difficulties in maintaining their depth when just submerged, exposing themselves inadvertently.

The Japanese continued to use midget submarines in other attacks in the Philippines and Guadalcanal.Their

design was continually reworked to create later models, including a five-man midget called the Koryu, and a piloted

torpedo—a suicide weapon—called the Kailon. At the end of the war there were some 400 midget submarines of

various kinds in Japan which were destroyed by the Allies.

However, the secret weapon never really lived up to the expectations of its proponents. While the notion of

attacking enemy shipping in the supposed security of their own harbours with re-usable midget submarines was a bold one, they remained a minor threat to allied shipping.

Significantly, the young submariners did not consider their chances of surviving these attacks as great, as they

prepared themselves onboard the parent submarines on May 31 1942 for the mission that would bring the war to Sydney. - Signals, Winter, 1992.

SignificanceThe attack on Sydney Harbour shipping by the Japanese midget submarines on the night of 31 May1942 really brought to Australia the realities of war. As nanny to Rear-Admiral Muirhead-Goulds three sons, Mrs Sutherland (then Miss Hayes) was more involved with the Admirals role in the event than many others - hence her complilation of this scrapbook. It contains contemporary newspaper reports of the event, memorabilia from the subsequent raising and touring of the submarine, and articles featuring the three young Muirhead Goulds as they took part in varied fund raising exercises .