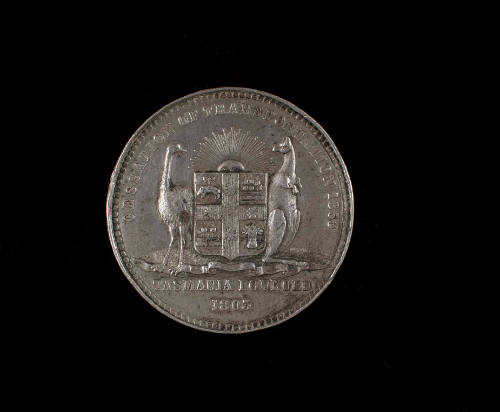

Cessation of Transportation 1853 - Tasmania Founded 1803

Date1853

Object number00026670

NameMedallion

MediumMetal

DimensionsOverall: 62 g, 58 mm

ClassificationsCommemorative artefacts

Credit LineANMM Collection

DescriptionA metal medallion produced by the colonial government, struck by the Royal Mint and issued to colonial school children commemorating the cessation of convict transportation to Van Diemen's Land in 1853 and the renaming of the former convict colony and founding of the Colony of Tasmania. Although dated 1853 the medallions were not issued until 10 August 1855.

The growth of free immigration to the Australian colonies in the late 1830s and early 1840s, the perception that convicts introduced vice and corruption into colonial society combined with a growing demand for locally elected political representation led to the birth of the anti-transportation movement. The movement eventually managed to convince Queen Victoria and the British parliament to stop transportation to the eastern part of the Australia, an event was marked by the issuing of the Cessation of Transportation Medallion.HistoryExtreme poverty was a fact of life for many in 18th and 19th century British society. In desperation, many resorted to crimes such as poaching, theft, robbery with violence and forging coins as the means to survive in a society without any social welfare system. This was countered by the development of a complicated criminal and punishment code aimed at protecting private property. Punishments were harsh with even minor crimes, such as stealing goods worth more than one shilling, cutting down a tree in an orchard, stealing livestock or forming a workers union, attracting the extreme penalty of 'death by hanging'.

Until the early 19th century English and Irish prisons were administered locally and were not the responsibility or property of central government, with the exception of King's Bench, Marshalsea, Fleet Prisons and Newgate Gaol which were all Crown prisons attached to the central courts. Prisons were used for the correction of vagrants and those convicted of lesser offences, for the coercion of debtors and for the custody of those awaiting trial or the execution of sentence - they were not places of rehabilitation. For nearly all other crimes the punishments consisted of a fine, capital punishment or transportation overseas.

The British Transportation Act of 1718 effectively established transportation to North America as a punishment for crime. British courts sentenced criminals on conditional pardons or those on reprieved death sentences to transportation. Prisoners were committed under bond to ship masters who were responsible for the convict's passage overseas in exchange for selling their convict labour in the distant colony.

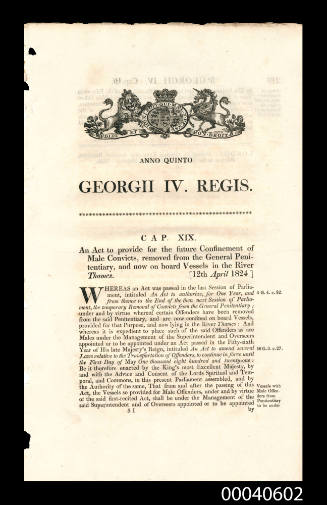

The loss of the American colonies in the War of Independence put an end to the mass export of British and Irish convicts to America. Many of the convicts in England's overcrowded jails were sent instead to the hulks (decommissioned naval ships) on the River Thames and at Portsmouth, Plymouth and Cork (Ireland) where they were employed on river cleaning, stone collecting, timber cutting and dockyard work while serving out their sentence

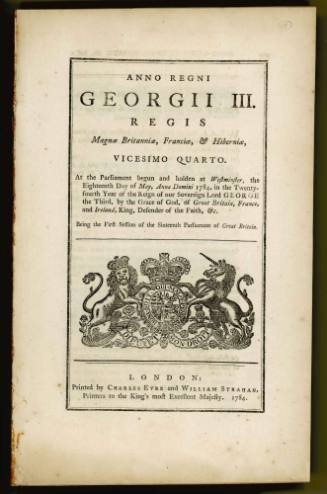

In 1784, under the Transportation and Penitentiaries Act, felons and other offenders in the hulks could be exiled to other colonies overseas which included Gibraltar, Bermuda and in 1788, the colony of New South Wales.

In January 1788 more than 700 convicts and their guards arrived at Port Jackson to establish one of the most isolated European colonies in the world. Over the next 80 years a further 160,000 convicts were transported from England to various parts of Australia to found or work in penal settlements that over time became, in some cases erroneously, bywords for crime, pain and punishment.

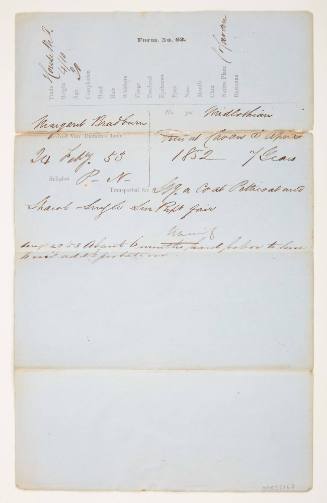

Between 1788 and 1868 over 160,000 men, women and children were transported to the Australian colonies of New South Wales, Van Diemen’s Land and Western Australia by the British and Irish Governments as punishment for criminal acts. Although many of the convicted prisoners were habitual or professional criminals with multiple offences recorded against them, a small number were political prisoners, social reformers, or one-off offenders.

The Convict System

Prior to 1842 all convicts in Van Diemen's Land and New South Wales, except those serving secondary punishment sentences or working on government projects, were employed under the Assignment System. Under this system convicts were assigned to work for private individuals, who provided shelter, food and clothing in exchange for the convicts' labour.

However, with more and more free settlers arriving every year in the colonies opposition to the continued transportation of felons to Australia grew. The most influential spokespeople were newspaper proprietors who were also members of the Independent Congregation Church such as John Fairfax in Sydney and the Reverend John West in Launceston. They argued through their respective newspapers that convicts acted as competition to honest free labourers, were the source of crime, vice and homosexuality within the colony and, as argued by the historian Babette Smith in her book Australia’s Birthstain (Allan and Unwin, 2008) inflicted a moral and hated stain on the free and non-emancipist colonial middle classes – interestingly unlike other critics of the system they were seldom concerned about its inhumanity and often suggested that it was too lax and rewarded those who had transgressed.

In April 1937 the British parliament formed the Select Committee on Transportation, also known as the Molesworth Committee after its chair, William Molesworth, to investigate Transportation and Secondary Punishment in New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land. After conducting a series of interviews and enquiries both in Australia and England the Molesworth Committee reported that whilst the Assignment System was too lenient on the one hand it was open to abuse and corruption on the other and recommended that the British and Colonial Governments scale down and eventually halt transportation to the Australian mainland (New South Wales) and introduce what became known as the Probation System into Van Diemen's Land and Norfolk Island.

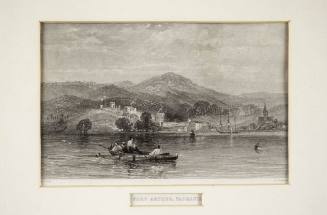

This new system was based on the convicts first having served part of their sentence in England prior to being transported out to Van Diemen's Land. In the colony they were classified into classes depending upon their crime and previous behaviour and then sent out to Probation Stations, or secondary punishment settlements such as Port Arthur, for at least two years. During this time the convict would have points credited or debited from an account - a certain number of points would entitle the convict to a remission on the remaining part of their sentence. After two years’ probation the convicts could receive a probation pass allowing them to work for wages while reporting to police. If they were well behaved they gained a Ticket of Leave and later a Conditional Pardon.

The continuation of transportation to Van Diemen’s Land coupled with a severe economic depression and growing political agitation for self-government saw the rise of a well-coordinated anti-transportation movement in the colonies in the early 1840s.

In 1847 the Reverends Browne and Smith formed the Launceston Association for Promoting Cessation of Transportation and later in 1849 the Anti-Transportation League of Van Diemen’s Land to politically oppose the transportation of convicts to the colony. By 1851 the League had expanded to the other colonies and branches had been established in New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and New Zealand and the name of the organisation was changed to that of the Australasian Anti-Transportation League – its flag and coat of arms almost identical to Australia’s current national flag and coat of arms.

Heeding the requests for self-government in August 1850 the British parliament passed the Australian Constitutions Act which granted the right of legislative power to the Australian colonies and called for each colony to partly nominated and partly elect legislative councils.

In Van Diemen’s Land these elections were held in October 1851 and members of the Australasian Anti-Transportation League won all 16 of the elected seats showing how popular the movement had become amongst the middle classes (those eligible to vote) and how opposed to transportation they had become. Despite the opposition of Lieutenant Governor William Denison the League dominated the Legislative Council and one of the first legislative actions taken was to petition Queen Victoria asking her to revoke the Order in Council permitting transportation to Van Diemen’s Land and Norfolk Island.

The growing political power of the League, coupled with the discovery of gold in both Victoria and New South Wales, led the British Government to discontinue transportation to the eastern side of Australia with the last convict ship, the ST VINCENT, arriving in Van Diemen’s Land in May 1853.

To celebrate the end of convict transportation, 50 years of European settlement and the re-birthing of the colony from the penal settlement of Van Diemen’s Land to the free colonial settlement of Tasmania, a ten-day Jubilee Festival was held in August 1853 (although Royal Assent for the new constitution and the new name had to wait until October 1855). Shops closed, and church services, thanksgiving ceremonies, parades, celebratory bonfires and firework displays were held throughout the colony; ships in the harbours were decorated with flags and pennants and Jubilee Arches constructed. The committee responsible for the celebrations also provided food and entertainment specifically for children rewarding all those who attended and participated with a special cake and a ticket redeemable for anti-transportation medallions which had been ordered from England.

On 10 August 1855, 9000 white medal anti-transportation medallions were issued to children throughout Tasmania with a further 100 bronze medals issued to those adults who played the most active roles in the anti-transportation movement.

SignificanceThe cessation of transportation to the eastern colonies of Australia in 1853 marked a new beginning for the colonies of Tasmania, New South Wales and Queensland. No longer seen as places of punishment but as destinations of desire with work, cheaper and better quality food, higher wages and plenty of land the colonies became magnets for hundreds of thousands of assisted and free migrants. after 1853