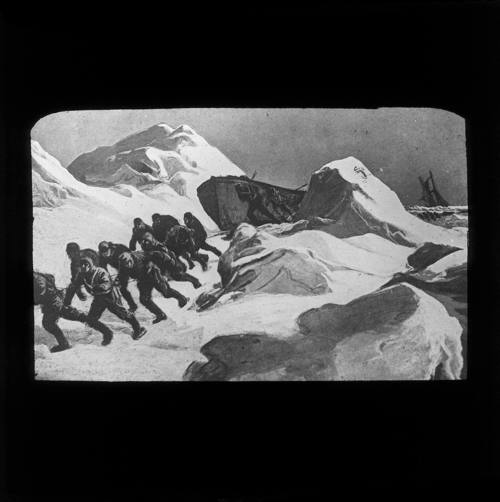

Ten men hauling the JAMES CAIRD over the ice

Datec 1920

Object number00054095

NameLantern Slide

MediumGlass, ink on paper

DimensionsOverall: 82 x 83 x 3 mm

ClassificationsPhotographs

Credit LineANMM Collection

DescriptionA black and white glass slide depicting a painting of ten men hauling the JAMES CAIRD across the ice with the stranded ENDURANCE in the background.

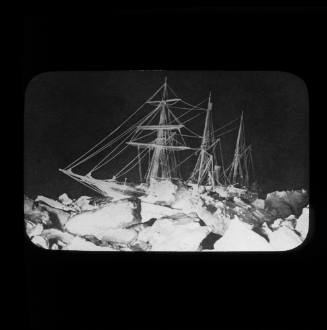

With spring the floes loosened and jostled, and the ship convulsed from the pressure of the ice. Shackleton ordered abandon ship on 21 October. Six days later Endurance was crushed, and with it the dream to cross the continent. Frank Hurley noted on 27 October 1915:

Our ship has put up a valiant fight and done honour to her noble name Endurance … Before leaving, I went below … and found the waters swirling in and already a foot above the floor, the ribs disrupting and tongues of ice driving through the sides.

— Frank Hurley, Shackleton’s Argonauts, p 64, 1948

Mere survival was now their only aim. Shackleton marshalled the 27 men and dogs to sledge to land, to the Antarctic Peninsula, Graham Land or Paulet Island, 650 kilometres northwest across the ice. Supplies had been left there by Nordenskjöld’s Swedish expedition crew marooned there after their ship Antarctic was beset in the ice and sunk in 1902. Progress proved impossible; the terrain was too difficult to cross. The 28 men managed only 2 kilometres a day, hauling the boats up and down ridges and ice hummocks.

Shackleton was now resigned to camping on the ice floe, their Ocean Camp, in the hope that it would carry them to safety. Shackleton and Frank Wild made preparations to escape. Led by carpenter and shipwright ‘Chippy’ McNish, they organised strengthening and reinforcement of the ship’s three lifeboats. They also named them. Meals of heavily rationed supplies, supplemented by huge numbers of seals, penguins and even the expedition’s dogs, were cooked on a stove improvised by Frank Hurley from oil drums and fuelled by seal blubber or penguin skins.

One day we added 300 penguins to our larder … The skins reserved for fuel, the legs for hoosh, the breasts for steaks, and the livers and hearts for delicacies. A seal was consumed by the party with restrained appetites for five days – just as long as his blubber lasted to cook him.

— Frank Hurley, p 84

After six long months the ice broke up beneath the men’s tents, while the ice pack opened and closed around them. The three lifeboats were launched and the men spent six days and nights in the Southern Ocean, fearful of killer whales, icebergs and huge seas, before reaching Elephant Island. All 28 men, thirsty, hungry and frostbitten, finally set foot on solid ground again after 17 months. Some went into a frenzy killing seals.

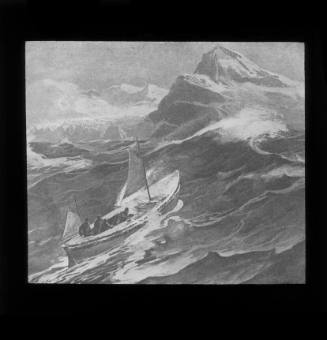

With little hope of rescue and winter looming, Shackleton immediately made plans to sail for rescue to South Georgia, 1,500 km northeast, aboard the largest of Endurance’s lifeboats, named James Caird. Anticipating a three-week passage, he took four weeks’ provisions — Bovril sledging rations (dried beef and fat), biscuit, powdered milk, sugar and nutfood (ground nuts and sesame oil), and several barrels of fresh water. He also selected Endurance captain Frank Worsley, second mate Tom Crean, sailor Tim McCarthy and two others — ‘Chippy’ McNish and John Vincent — practical additions to the crew who were also potential troublemakers to those left behind.

In a remarkable feat of navigation, over 17 stormy days, Worsley, Shackleton and the small crew navigated the seven-metre boat to reach the island on 10 May. They arrived on the west coast, but the whaling stations were on the east. More than 40 kilometres of poorly charted, rugged mountains, glaciers and crevasses separated them. And they were exhausted.

Over 36 hours Shackleton, Worsley and second officer Tom Crean marched, climbed and glissaded (slid), taking several wrong turns, finally arriving in Stromness to the familiar steam whistle from the whaling station. They were unrecognisable to its manager, who had greeted them 18 months earlier on the voyage south. There they learnt of their supply party’s misadventures in the Ross Sea and that the war was not yet over.

HistoryWith spring the ice floes loosened and jostled, and the trapped ENDURANCE convulsed from the pressure of the ice. Shackleton ordered abandon ship on 21 October. Six days later ENDURANCE was crushed, and with it the dream to cross the continent. Frank Hurley noted on 27 October 1915:

"Our ship has put up a valiant fight and done honour to her noble name ENDURANCE … Before leaving, I went below … and found the waters swirling in and already a foot above the floor, the ribs disrupting and tongues of ice driving through the sides.

— Frank Hurley, Shackleton’s Argonauts, p 64, 1948

Mere survival was now their only aim. Shackleton marshalled the 27 men and dogs to sledge to land, to the Antarctic Peninsula, Graham Land or Paulet Island, 650 kilometres northwest across the ice. Supplies had been left there by Nordenskjöld’s Swedish expedition crew marooned there after their ship Antarctic was beset in the ice and sunk in 1902. Progress proved impossible; the terrain was too difficult to cross. The 28 men managed only 2 kilometres a day, hauling the boats up and down ridges and ice hummocks.

Shackleton was now resigned to camping on the ice floe, their Ocean Camp, in the hope that it would carry them to safety. Shackleton and Frank Wild made preparations to escape. Led by carpenter and shipwright ‘Chippy’ McNish, they organised strengthening and reinforcement of the ship’s three lifeboats. They also named them. Meals of heavily rationed supplies, supplemented by huge numbers of seals, penguins and even the expedition’s dogs, were cooked on a stove improvised by Frank Hurley from oil drums and fuelled by seal blubber or penguin skins.

"One day we added 300 penguins to our larder … The skins reserved for fuel, the legs for hoosh, the breasts for steaks, and the livers and hearts for delicacies. A seal was consumed by the party with restrained appetites for five days – just as long as his blubber lasted to cook him."

— Frank Hurley, p 84

After six long months the ice broke up beneath the men’s tents, while the ice pack opened and closed around them. The three lifeboats were launched and the men spent six days and nights in the Southern Ocean, fearful of killer whales, icebergs and huge seas, before reaching Elephant Island. All 28 men, thirsty, hungry and frostbitten, finally set foot on solid ground again after 17 months. Some went into a frenzy killing seals.

With little hope of rescue and winter looming, Shackleton immediately made plans to sail for rescue to South Georgia, 1,500 km northeast, aboard the largest of Endurance’s lifeboats, named JAMES CAIRD. Anticipating a three-week passage, he took four weeks’ provisions — Bovril sledging rations (dried beef and fat), biscuit, powdered milk, sugar and nutfood (ground nuts and sesame oil), and several barrels of fresh water. He also selected Endurance captain Frank Worsley, second mate Tom Crean, sailor Tim McCarthy and two others — ‘Chippy’ McNish and John Vincent — practical additions to the crew who were also potential troublemakers to those left behind.

In a remarkable feat of navigation, over 17 stormy days, Worsley, Shackleton and the small crew navigated the seven-metre boat to reach the island on 10 May. They arrived on the west coast, but the whaling stations were on the east. More than 40 kilometres of poorly charted, rugged mountains, glaciers and crevasses separated them. And they were exhausted.

Over 36 hours Shackleton, Worsley and second officer Tom Crean marched, climbed and glissaded (slid), taking several wrong turns, finally arriving in Stromness to the familiar steam whistle from the whaling station. They were unrecognisable to its manager, who had greeted them 18 months earlier on the voyage south. There they learnt of their supply party’s misadventures in the Ross Sea and that the war was not yet over.

SignificanceThe collection of slides of Antarctic voyages compiled by Charles Ford documents aspects of the technical and geographical mapping work, personal challenges, daily lives, social dynamics and the landmarks, icescapes, waterscapes and environments the men encountered.

October 1915

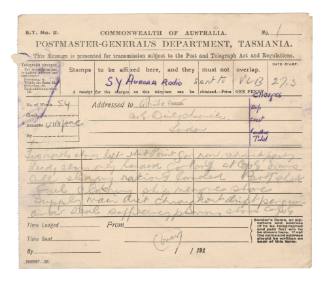

Joseph Russell Stenhouse

27 March 1916