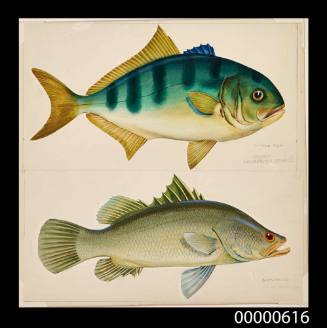

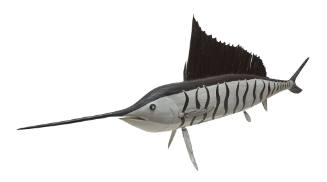

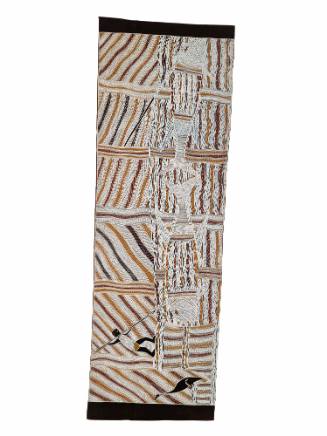

Rätjuk (Barramundi)

Date2018

Object number00055924

NameFish carving

MediumEarth pigment on wood

DimensionsOverall: 175 × 700 × 75 mm

Copyright© Guykuḏa Munuŋgurr

ClassificationsArt

Credit LineAustralian National Maritime Museum Collection

Collections

He has distinguished himself as a completely innovative sculptor who pioneers new materials and techniques.

One of the themes that he has pursued is the natural representation of animal species without reference to their sacred identity. This is one such work.

However for stricter adherents of Yolŋu law the naturalistic representation of totemic species is a sacrilege. Despite his protestations of innocence in representing figurative sculpture of crocodiles (which are related to his mother's clans respectively) he was counselled away from this approach. In Yolŋu law Rangga or sacred objects are never revealed and their shape can only be guessed at. It is assumed that it was the similarity of these manifestations of totems with such raqga which caused elders to veto his naturalistic representations of species. He specifically disavows any sacredness for these works. They are 'just art' or 'just for fun'.

An area where he has been able to play with form and not attract negative attention is in his representations of fish. This work is part of a series begun in 2018. As a Homeland resident living on the coast of a vibrant sea estate which includes estuaries and coral reefs, big rivers and ocean he feeds himself and his family with his knowledge of the land. This familiarity allows him to shape these sculptures from memory not from images or life.

2018