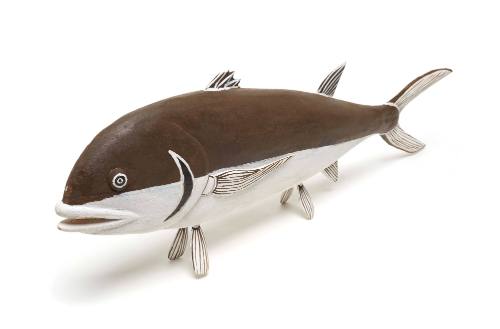

Ŋuykal (Kingfish)

Date2018

Object number00055931

NameFish carving

MediumWood

DimensionsOverall: 230 × 720 × 60 mm

Copyright© Guykuḏa Munuŋgurr

ClassificationsArt

Credit LineAustralian National Maritime Museum Collection

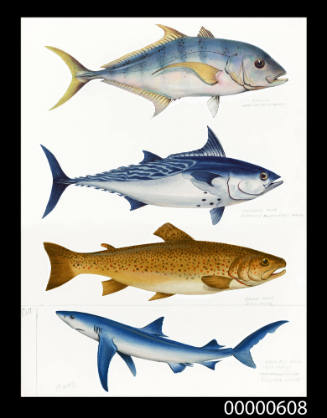

DescriptionWooden carving by Guykuḏa Munuŋgurr of Ŋuykal (Kingfish). Ŋuykal is specifically non-sacred and depicts the fish itself in its physical form. But Ŋuykal is a very sacred being with a deep story and Songline which connects all the way from Groote Eylandt to Milinŋgimbi. In East Arnhem it is the Maŋgalili clan which is most closely associated with Ŋuykal the Ancestral Kingfish (Turrum, carangoides emburyi).

It is the travelling of this fish (up freshwater rivers to breed) that created important ties with relative clans. Ŋuykal’s travelling included a path from Dhonydji to the Wayäwu River which Ŋuykal passes through Dhälinbuy, a site where the Wangurri clanspeople have settled. At Wayawuwuy, Ŋuykal changed into the hollow log Milkamirri.

HistoryIn the late Dry and early Wet Season Yolŋu still gather to sacred places known as Yelaŋ where they wait for this fish to bring itself to be speared. The bones are left at the site and any fish, which is speared but not landed, is regarded as sacred. This stems from the original Maŋgalili Ancestral Hunter, Muwandi.

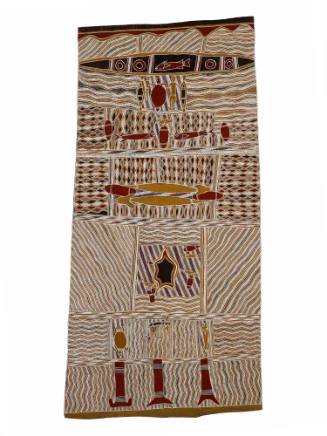

This sacred country under the coastal waters of the area of Djarrakpi (Cape Shield) and into which the sacred rock has its foundation. Ancestral Hunter Muwandi climbed up on this anvil shaped rock that rises above the lower tides to spear fish. With the two-pronged hook spear he speared Yambirrku the Ancestral parrot fish. The parrot fishs' special spiritual qualities make reference to the procreative freshwaters of the Wayawu River in Maŋgalili country and the ancestral kingfish Ŋuykal who breeds there and eats/carries the yoku or corm/child of the lily.

When Muwandi caught Yambirrku he went back to his camp and made a special ground to eat the fish. The ground was to become the sacred Yiŋapuŋapu at Djarrakpi, the original canoe shaped low relief sand sculpture used to mother, confine, release the essence and spirit of the Maŋgalili people and realm at mortuary. From his camp Muwandi witnessed the cloud massifs Waŋupini form on the horizon taking up from the sea freshwater to rain back over the sea to Djarrakpi the freshwaters that flowed through the Wayawu estates.

Still today Yolŋu spearing Yambirrku from Yinitjuwa have the responsibility to prepare, eat and discard scraps all within the confines of a Yiŋapuŋapu. This reaffirms the Maŋgalili connections Djarrakpi has with the tides and the sea, the flow and freshwaters of the Wayawu River and the horizons return through the skies and tides the life force of the Maŋgalili.

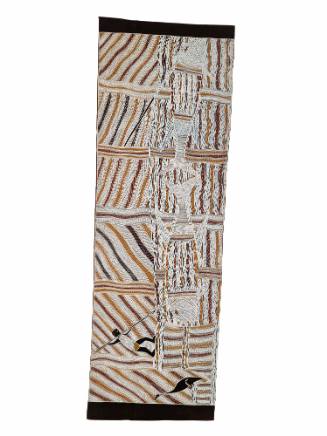

The giant spirit boulder Dukurrurru gouged the bed of this river, as it crashed down from Burrawanydji to the coast. The ancestral woman Nyapaliqu used rushes growing along the Wayawu River to make baskets for collecting Yoku water lily bulbs which are washed down the river during flood along with lily leaves. The freshwater runs down the Wayawu River where the Maqgalili rock stands, past and through Dhalwaqu, Munyuku, Djapu clan country before meeting the sacred waters of the Dhudi-Djapu clan at Dhuruputjpi. Here the water of the Maqgalili clan, coming from the rock, slips under the waters of Dhuruputjpi past the shark, to surface again to empty into Blue Mud Bay at what is marked on the map as Grindall Bay. The central panel is this subterranean passage used by Ŋuykal and ancestral shark Mana.

The Maŋgalili dance the Ŋuykal at Wayawu where men enact a search for the sacred rock Dhukurru - men with their spear thrower the swimming tail of the totem king fish Ŋuykal. They dance as if to find Dhukurru as it marks a spot designated as sacred by the Yirritja moiety creator beings. Here the waters are most sacred to the Maŋgalili, ancestral identity past and future stems from here, where Ŋuykal finding the Dhukurru coming up against the Wayawu flow to the upper reaches of freshwater changes sex to give life. The group of dancing men having found the sacred site, send out its leader with the feathered dilly bag carried in the mouth and spears at ready to encircle the site, still in dance of the king fish, checking it out for adversary before setting in.

Ŋuykal feed on the corm of the waterplant Aponogetum. The corms are the child within; these mark the Maŋgalili soul.

SignificanceIn Yolŋu law Rangga or sacred objects are never revealed and their shape can only be guessed at. It is assumed that it was the similarity of these manifestations of totems with such Rangga which caused elders to veto Guykuḏa Munuŋgurr naturalistic representations of species. He specifically disavows any sacredness for these works. They are 'just art' or 'just for fun'.

An area where he has been able to play with form and not attract negative attention is in his representations of fish. This work is part of a series begun in 2018. As a Homeland resident living on the coast of a vibrant sea estate which includes estuaries and coral reefs, big rivers and ocean he feeds himself and his family with his knowledge of the land. This familiarity allows him to shape these sculptures from memory not from images or life.