Letter addressed to Mrs Withers regarding HMAS VOYAGER Naval memorial ceremonies

Date1964

Object numberANMS1464[050]

NameLetter

MediumPaper

DimensionsOverall: 214 × 170 mm

ClassificationsEphemera

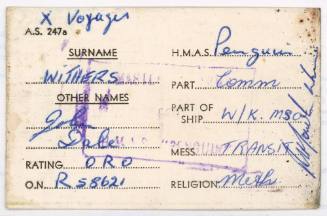

Credit LineAustralian National Maritime Museum Collection Gift from John Withers OAM

DescriptionJohn Aaron Russell Withers joined the Royal Australian Navy on 12th January 1962. Withers survived the tragic collision between HMAS Voyager and HMAS Melbourne on the 10 of February 1964, an incident that resulted in the loss of 82 lives and the sinking of HMAS Voyager. This stands as the worst peacetime disaster in the history of the RAN. His collection of images, telegrams and pamphlets provide insight into Voyager's operational history and the impact of the collision on Voyager survivors.HistoryJohn Aaron Russell Withers joined the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) as a 20 year old on 12th January 1962. He travelled from Herberton in far North Queensland to Brisbane to enlist, and then on to HMAS Cerberus - RAN recruit training depot in Victoria. Here he underwent training in the communications branch as a radio operator. This involved studies in Morse code, typing, flag waving, flag recognition, speed printing, and cryptography. On the 4th December 1962 Withers was promoted to Ordinary Radio Operator and posted to HMAS Voyager.

The first of three Australian built Daring Class Destroyers, Voyager was laid down at Cockatoo Island Dockyard on the 10 October 1949 and Commissioned on the 12 February 1957. Like its sister ships Vampire and Vendetta, Voyager drew from 1940s UK destroyer designs, modifying ship ventilation and air conditioning for Australian conditions. The Daring ships stand as the first prefabricated all welded ships to be built in Australia, using light alloys in the superstructure and in interior sub-divisions and fittings – and at the time of commissioning were the largest conventional destroyers built for the RAN.

(Source: https://www.navy.gov.au/hmas-voyager-ii)

On the 31st January 1963 Withers deployed on board Voyager as part of the Far East Strategic Reserve (FESR). This trip saw Voyager call in to Singapore, Sri Lanka (then Ceylon), Hong Kong, Japan, and the Philippines – in addition to exercises in the South China Sea. Withers recalls the deployment:

“It was a multi-national fleet to show the flag and keep the peace if any country was thinking of flexing muscles. We joined this fleet for exercises in the Indian Ocean between Malaya and Ceylon. It consisted of some of the largest U.S. aircraft carriers of the time, back in 1960’s.”

(Source: See Volunteer Oral History Project Archive for full interview)

Voyager returned to Australia in August 1963 and underwent a six month refit at Williamstown. The ship sailed for Sydney late January 1964, with an intended return to the FESR as Australia’s representative for the Tokyo 1964 Olympic Games. On the way to Sydney Voyager was engaged in exercises with aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne off the coast of Jervis Bay.

On the evening of the 10th of February 1964 Voyager was acting as plane guard for Melbourne during flying exercises. Voyager’s position was starboard side, forward of Melbourne, as aircraft were launched, and was to go to port side, aft, whilst aircraft were coming in to land. The intended procedure for Voyager to reach port side was for the vessel to turn right and circle to reach landing position via Melbourne’s stern.

At the time of a change of course, Captain Duncan Stevens of Voyager was on the bridge, but not actually in command, this left to junior raining officer - LEUT David Price. Melbourne was also under the control of a Junior Officer of the Watch doing his second time in Command while working with aircraft. On Voyager, Price decided to increase the ships speed and turn left to cross in front of Melbourne. Voyager was not travelling fast enough to pass across, its port side colliding with Melbourne’s bow.

Wither’s recalls the collision and aftermath:

I was in my bunk on the far side of Communicators mess 3DZ below the cafeteria, as I was due to go on shift at midnight and wanted some sleep. I was restless and not asleep when at approx. 2150 (9.50 p.m.) an urgent pipe was made “HANDS TO COLLISION STATIONS.”

I jumped out of bunk and almost immediately we heard a very loud bang and the ship healed violent to starboard, then shortly righted herself. The lights went out and the very weak emergency lighting came on. Bunks and lockers were jumbled and strewn every which way. The 13 sailors in the mess all crowded to the ladder to get up into the cafeteria, but a refrigerator had blocked the hatch.

We remembered there was an escape hatch nearby in the Petty Officer Mechanical Engineer’s (POME) mess in our same compartment. We made our way through the tangle and were able to get the hatch open. I was the second person out. We slid down the ship’s side into the water.

RO Owen Sparkes and I swam away and found a wooden plank to hold onto until we could get to a life raft. We had no life jackets and I wore only the bottom half of short pyjamas. Others didn’t have that. The water was warm, and the night dark.

We were dumb founded and could not believe our ship, our home had just sunk taking 82 good sailors to their lonely watery grave. The two of us got to a life raft and not being injured, but much bruising, and the life raft over flowing, we held onto rope loops on the outside.

(Source: See Volunteer Oral History Project Archive for full interview)

Withers was transported to HMAS Creswell following the crash by Sea Air Rescue Vessel Air Nymph, and did not find out what caused the collision until the next day on the morning news. 82 lives were lost - 14 officers, including the commanding officer Duncan Stevens, 67 sailors and one civilian dockyard employee. Many of the sailors were junior recruits picked up at HMAS Williamstown only days prior. Only three bodies were recovered, that of CAPT Duncan Stephens, LEUT Cook Leonard Charles Lehman, and AB Seaman R.W. Parker.

(Complete account of SAR Air Nymph rescue operation https://www.navyhistory.org.au/the-melbournevoyager-collision-untold-story/)

Following spending the night at HMAS Creswell Withers was transported to HMAS Penguin where he underwent treatment for minor injuries and was issued seven days survivors leave. At the time no form of counselling was offered. After his leave, Withers was posted to HMAS Quiberon where “...a fast 360 degree turn” was employed at one point in order to test the seagoing ability of Voyager survivors on board.

After Quiberon, Withers transferred to HMAS Stuart (1964-1965). Stuart was designated to carry out acceptance trials on the Navy’s newly installed top-secret IKARA anti-submarine missile and torpedo. The IKARA was missile carried, and designed to be fired up to 15 kms from the ship, the torpedo released to search and target a submarine. Trials were conducted on the Barrier Reef off Lady Elliot Island.

In 1968 Withers was posted for a year to HMAS Tarangau, former RAN base in Manus Island Papua New Guinea. Here he was a shore base radio operator, chronicling his deployment via the self-publicised ‘Tarangau Telegraph’ periodical. Withers also experienced shore based placements at HMAS Penguin (1965) and HMAS Albatross (1968). Withers was later assigned to HMAS Hobart (1969) and deployed on the vessels third trip to Vietnam in 1970. After four vessel and three shore postings, John Withers signed off from the RAN on the 11 January 1971 at the age of 29.SignificanceThis collection of material is significant as an account of the HMAS Voyager tragedy through the personal documents of survivor John Withers. On the 10 of February 1964 HMAS Voyager collided with aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne during a series of flight exercises near Jervis Bay. 82 lives on Voyager were lost, and the destroyer sunk. The collision stands as the worst peacetime disaster in the history of the RAN. HMAS Voyager was Withers' first ship posting, having joined only a year prior on the 31 January 1963 as a radio operator. Images taken at HMAS Creswell following the collision show Voyager survivors - including Withers - in a state of severe shock. A partnered 1964 Sun newspaper clipping includes testimonies from Voyager survivors on their escape the night of the collision. Concerned telegrams from Withers' family, his HMAS Penguin base card marked 'X Voyager', and annotated Voyager memorial service pamphlets are further poignant documents. Together, the material forms a comprehensive archive profiling the aftermath, and memorialization, of the HMAS Voyager tragedy.