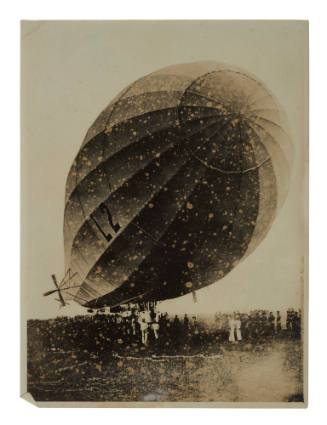

Coastal Class 23 airship over a Channel convoy

Subject or historical figure

Sir Lionel Hooke

(Australian, 1895 - 1974)

Date23 May 1917

Object number00056179

NamePhotograph

MediumPaper

DimensionsOverall: 188 × 255 mm

ClassificationsPhotographs

Credit LineAustralian National Maritime Museum Collection Gift from Maria Teresa Savio Hooke OAM

DescriptionPhotograph picturing a Coastal Class 23 airship over a Channel convoy.

Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) Coastal Class airships were the larger counterpart to the Sea Scout Zero with a more powerful engine and additional flight crew. Whilst the addition of a navigator and a coxswain aboard presented the Coastal Class as advantageous to the SS Zero, its larger size made it less responsive in manoeuvrability.

HistoryRNAS SS (Sea Scout) Zero airships were primarily tasked with submarine hunting, mine spotting, and fleet escort duties in an area extending along the southern coast of England to the French Coast. Further operations occurred along the Bristol Channel. Each S.S Zero airship consisted of a crew of three – the pilot, who controlled the ship from the central cockpit, the signaller/wireless operator, who sat forward of him, and the mechanic, who occupied the aft cockpit. The airship envelopes were a non-rigid cigar shape, and had a hydrogen capacity of 50,000 cubic feet.

The larger Coastal Class airships held a more powerful engine and additional flying support crew in the form of a navigator and a coxswain. This freed the Commanding Officer from piloting duties, which was particularly advantageous during landing procedures where the CO would be exclusively focused on relaying signals to the ground landing party.

Lionel Hooke compares the S.S Zero and Coastal Class:

“Being relatively smaller in size, the S.S Zero airships were also more manoeuvrable than the Coastal Class ships. This fact was particularly noticeable when flying over land masses, were unstable air conditions were more often encountered. The big coastals were much slower a answering the helm, so one always had to avoid get too close to anything that was likely to endanger the safety of the ship”

Lionel Hooke 1895-1974 (later Sir Lionel) joined Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial-Trans Antarctic Expedition of 1914-17 at the age of 19, serving as the wireless operator on the Ross Sea Party supply ship SY AURORA. Hooke was appointed by recommendation of his employer Marconi, soon to become AWA (Amalgamated Wireless Australasia). His persistence and inventiveness in establishing wireless contact was widely praised during AURORA’s drift in 1915-16.

After learning of his brother's death at Gallipoli Hooke left AURORA while plans were being made for the Ross Sea relief voyage. Early in 1916 he enlisted in the New Zealand division of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve and sailed to the UK as a sub-lieutenant. After serving on submarine chasers, Hooke was later assigned to minesweepers operating out of Queenstown (Cobh), as part of the Irish Coast Command. After studying at Greenwich Naval College Hooke was then granted a commission in the Royal Navy and given command of a rescue tug that was primarily deployed to salvage ships that had been damaged by torpedoes or mines.

Eager to play a more active role in the war, Hooke applied for a transfer to the Royal Naval Air Service in 1917. His first posting was to the RN training college at Cranwell, where he was assigned to airships due to his anti-submarine experience. Hooke’s course focused on free ballooning, airship operations and handling procedures, and instruction on the supervision of maintenance personnel.

Upon completion of his training at Cranwell Hooke was posted to the RNAS airship sub-station at Bude, on the coast of Cornwall. This was one of three sub-stations attached to the main base at Mullion, the others were located in Laire, near Plymouth and Toller, on the north coast of Dorset. Hooke served at all three sub-stations and was for a period Commanding Officer at Bude. Each of the three substations held up to two Sea Scout - S.S. Zero airships, and Hooke flew out on a number of patrols, operations that would begin before dawn and last from 10 to 14 hours.

In an interview in 1974, Hooke described the standard procedure of an airship mission

'We made regular patrols of those areas that were known to be most suitable for enemy submarine operations. These were generally limited to within 50 miles of the coast, because the Germans preferred to work close inshore and obtain visual sights from points along the coastline as aids to their navigation. When planning our patrols we paid particular attention to shipping routes and movements, and, most importantly, the time of day. This gave us the tremendous advantage of getting the morning or evening sun behind us and thus making it easier for us to see, without being seen. It was for this reason that we left our base so early in the morning and flew well out to sea before the sun rose.

Anti-submarine and mine spotting patrols were mostly flown at a height of around 2,000 feet. We could usually depend upon a 25 to 30 knot breeze at that altitude, which enabled us to control our speed range at anything between 25 and 75 knots, according to the circumstances. By heading the ship into the breeze and throttling back the engine, it was possible to remain stationary over a given spot, yet still maintain sufficient airspeed over the rudder and elevators for complete control of the ship. The manoeuvrability of our airships, together with the tremendous range of visibility which they provided, made them perfect observation platforms.'

In September 1918 Hooke’s airship was shot down in the English Channel by friendly fire on his last flight of WWI. A minesweeper misfired during a routine mine disposal operation, catching the envelope of Hooke’s airship. After a short period in hospital with pneumonia Hooke was sent to the Scilly Isles on his last RN posting, supervising the cleaning up of a partly constructed aerodrome near St Marys.

Hooke returned to Australia in 1919 to Amalgamated Wireless Australasia where he was pivotal in the development of live radio broadcasts, direct wireless telegraphy, and the design of the automatic distress transmitter (patented 1929) – forerunner of the EPIRB. In 1945 Hooke became managing director and in 1962 succeeded his friend and mentor Sir Ernest Fisk as chair of AWA. He was awarded a knighthood in 1957 for his services to industry and coronation medals in 1937 and 1953.

Hooke retained a long-lasting interest in airship operation, remarking shortly before his death in 1974:

'On a final note, you might be interested to note that during WWII some serious consideration were given to the building of a fleet of small airships, similar to the Zeros, for patrol work in Australia coastal waters. This scheme did not eventuate but I believe that it was a good idea and would have proven successful – as evidenced by the US Navy blimps around the American coastline' – Lionel Hooke

(Quotes sourced from the 1418 Journal, published by The Australian Society of World War One Aero Historians 1975-6, Chapter by EA Watson on Lionel Hooke, inclusive of complete oral history account with Hooke. Held in Vaughn Evans Library)

SignificanceThis material relates to Sir Lionel Hooke, wireless operator on SY AURORA for Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914-17 (the ENDURANCE expedition). Following his time on SY AURORA Hooke was involved in the first state live radio transmission in 1920 with Amalgamated Wireless Australasia (AWA) and the re-equipping of the Australian coastal radio network in 1922. He was awarded a knighthood for his services to the industry in 1957, coronation medals in 1957 and 1963, and made chair of AWA in 1962.