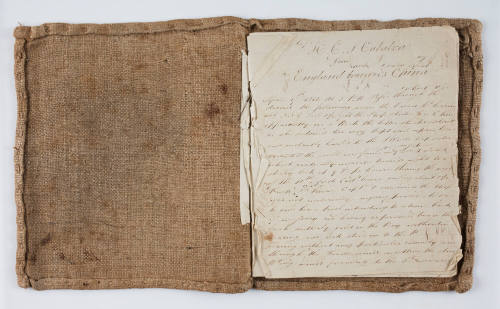

The voyage and shipwreck of The East India Company ship CABALVA

Author

Thomas Ingram

Date1818

Object number00027224

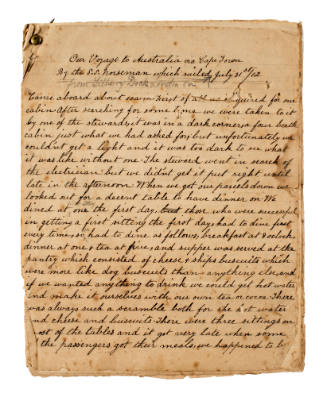

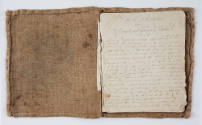

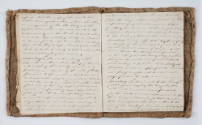

NameManuscript diary

MediumCloth, Ink on paper

DimensionsOverall: 205 × 18.1 × 0.5 mm, 0.1 kg

Copyright© Geoffrey P Ingram

ClassificationsBooks and journals

Credit LineANMM Collection Gift from Geoffrey P Ingram

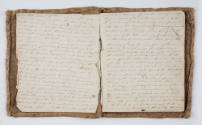

DescriptionManuscript diary of midshipman Thomas Ingram titled 'HCS CABALVA from England towards China' dated '17th April 1818 at 5pm'. It recounts the voyage, subsequent ship wreck and rescue of the CABALVA in 1818. The last entry is dated Sunday 25th on the voyage home from St Helena to England.

This diary is written while Thomas Ingram is travelling on the HASTINGS towards England. It discusses the crew being rescued by the HMS CONGUOVER and some of the crew obtaining passage on the MAXICIENNE.HistoryThe English East India Company, known as the Honourable East India Company was founded on 31 December 1600.The Company was established to provide ships, expertise and capital for trading voyages to the East Indies.

In 1609, in order to provide superior ships (and crew) for the voyages east, the company established a dockyard at Deptford on the River Thames which was soon producing highly innovative, heavily armed merchant vessels.

These superior ships, known as East Indiamen, along with good trading acumen, a crown supported trading monopoly and a fair share of luck saw the Honourable East India Company become the major European trading company in the Indian Ocean.

However, the very success of the Company operations in India, forced the British government in 1757 to intercede and subject the actions of the company to government approval. In 1813, the year the CABALAVA made its first voyage to India, the British government revoked the Honourable East India Companies monopoly of all trade to India and threw it open to the public. However the Company was allowed to retain the monopoly of trade to China.

The 1200 ton CABALAVA was built in the Deptford Yards of the Hon East India Company in 1811. The ship was a typical three masted, wooden hulled, copper sheathed and fastened East Indiamen, heavily decorated, well-armed (the Company stipulated that their ships carry at least 22x9 pdrs and 4x4 pdrs and in some cases as many as 54 guns) and finished internally as much for comfort and luxury of captains, officers and passengers as for cargo capacity. According to Kemp {Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea) - East Indiamen were generally regarded as the soundest ships afloat and 'the lords of the ocean'.

The CABALVA had made three previous voyages to Bombay, Calcutta and China(1813, 1814 and 1816) with carrying Company cloth or broadcloth, gunpowder, beer, spirits, salted meats and bullion and returning with sugar, salt, cowries, pepper, lacquer, silks, spices, tea, calico and china ware.

On its fourth and final voyage the vessel left the Downs sometime between 12 and 16 April 1818 under the command of J.Dalrymple Esquire, also on board was a 15year old midshipman, Thomas Ingram, who wrote a most vivid account of the voyage and the subsequent wrecking.

After rounding the Cape of Good Hope, CABALVA along with the two other Company ships, Lady Melville and Scales by Castle decided to head for Bombay to repair damage the CABALVA had sustained when it struck a submerged object.

'it was determined that the Ship rounding the Cape haul up for Bombay to repair as also to avoid the heavy gales which are experienced in running down the east in a high latitude during the winter season.'

Unfortunately the fleet encountered severe storms and the vessels were separated.

On the 7 July, the CABALAVA'S lookout reported that breakers could be seen ahead and on the lee bow, despite the best endeavours the vessel struck heavily on the Carragos Carjados (Cargados Carojos) Shoals which lie some 600 miles to the east of Madagascar, and began to breakup.

'Finding the ship was breaking up fast and that most of her bottom was knocked out as her cargo was floating to windward of her and that there remained no chance of saving her, cut away her masts to ease her which had the

desired effect'

Ingram reports the abandoning of the ship and the taking to the boats of the ships company along with some supplies. The Crew head for precarious shelter of some sandbanks.

'About 2PM most of the crew had reached the sandbanks in an exhausted state from having recorded many severe bruises and cuts amongst the corral (sic) Rocks and breakers when washed onshore '

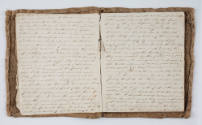

What follows is a most vivid account of shipwreck and survival at sea, the salvaging of the ships boats, the erection of shelters and digging of wells,

'5PM . The party returned from the wreck with the large cutter, and providentially procured Hosburgh (East India Pilot), norie (nautical tables),2 sextants and a Quadrant and a small quantity of Provisions;'

The problems of food, water and discipline on the small islets are detailed by Ingram, who as a midshipman, would have been partly responsible for discipline.

'11.30AM.. .The Seamen breaking open packages of every discription(sic), clothing themselves and searching principally for wine and spirits; only one cask of Brandy reached the breakers which the Cheif (sic) officers order'd to be stove, notwithstanding several hands were soon intoxicated. In the course of the day caught a shark and by much difficulty obtain'd a fire by friction, cook'd him and with a small quantity of wine made our only meal'

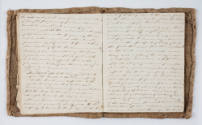

On Tuesday 14th July, Ingram reports that the ships cutter was provisioned and a select crew chosen to undertake a hazardous voyage to the Isle of France to seek help. Transported the large cutter to the edge of the bank for launching at daylight the next morning but kept her rudder and sails in the principal tent to prevent her being run away with.

'At 7AM, provisioned the boat and took our uncertain leave of our shipmates, launched her with crew consisting of Mr Franken, 6th Officer, Mr Atres, Purser, the only one acquainted with the (Isle of France) and 8 of our stoutest

Hands,...gave her three heartfelt cheers when she made sail, and was soon out of our sight, with our best wishes as all our lives entirely depended on her success'.

And then the long wait for rescue, with obvious concerns for their shipmates and

themselves, 'The weather unfortunately bad for our boat which caused a depression of

spirits to many' and then finally rescue. Ab(ou)t 2.30PM. conversing upon our condition and the probability of

assistance during the week, in the main tent we were all rous'd from our desponding circle by the boats wains voice crying out a sail, a sail! All hands were soon on the edge of the bank and cheer'd with the pleasing sight of a Ship

and Brig; the effect of this sudden transition, from an uncertainty to safety was displayed by our shipmates in various ways; most of the men were frantic, but the offrs feelings were far different and expressed in silence; their joy

occasioned by this providential deliverance, was lessened by the loss of their Captain."

SignificanceShip board manuscripts are quite rare, especially detailing a shipwreck and subsequent rescue.

The style of writing, especially between the informal account of the wrecking, which provides insights into human behaviour under stress, is in startling contrast to the formal, ordered logbook, which follows Ingram's rescue by the two Royal Navy vessels, CHALLENGER and MASICIENNE.

Captain Ingram Chapman

1825 -1829

Elizabeth Moulding

1912

![My log [a voyage from England to Australia on board the SS DURHAM in 1875]](/internal/media/dispatcher/212338/thumbnail)