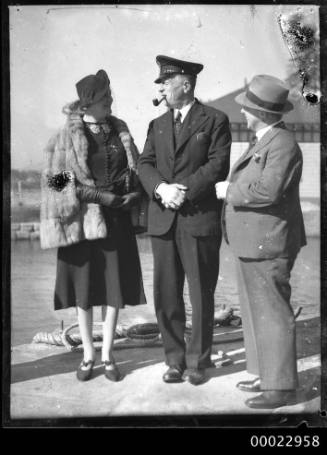

Count Felix Graf and Countess Ingeborg von Luckner, at the Man O' War Steps in Sydney

Photographer

Samuel J Hood Studio

(Australian, 1899 - 1953)

DateMay 1938

Object number00022976

NameNitrate negative

MediumEmulsion on nitrate film.

ClassificationsPhotographs

Credit LineANMM Collection

Terms

Samuel J Hood Studio

May 1938

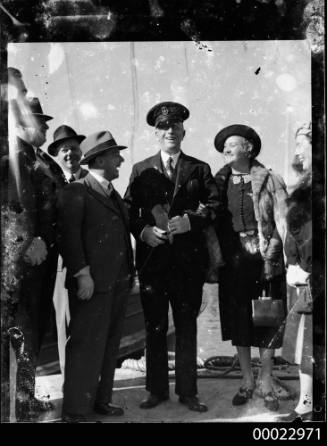

Samuel J Hood Studio

May 1938

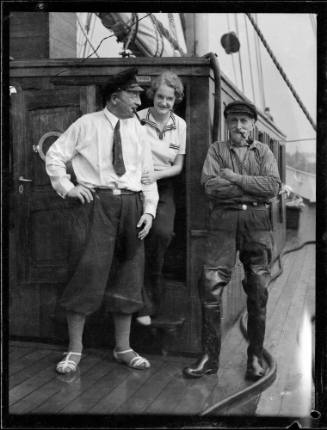

Samuel J Hood Studio

3 June 1938

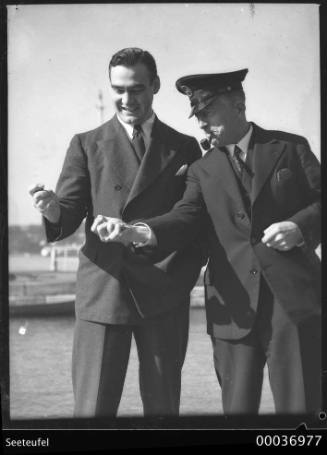

Samuel J Hood Studio

20 May 1938

Samuel J Hood Studio

20 May 1938

Samuel J Hood Studio

20 May 1938

Samuel J Hood Studio

May 1938

Samuel J Hood Studio

May 1938