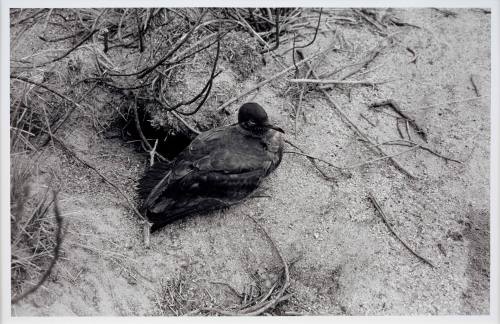

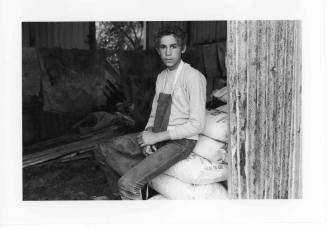

Muttonbird next to burrow

Photographer

Ricky Maynard

(1953)

Date1985

Object number00018083

NamePhotograph

MediumSilver gelatin print, fibre based paper

DimensionsOverall: 24.4 mm, 0.03 kg

Display dimensions: 24 × 35 mm

Mount / Matt size (B Fini Mount): 407 × 560 mm

Display dimensions: 24 × 35 mm

Mount / Matt size (B Fini Mount): 407 × 560 mm

Copyright© Ricky Maynard

ClassificationsPhotographs

Credit LineAustralian National Maritime Museum Collection

DescriptionThis photograph of a mutton bird near its burrow was taken by photographer Ricky Maynard in 1985. Ricky Maynard is a documentary photographer and for generations his family have returned each year in March to the islands of Bass Strait to catch mutton birds and prepare them for sale.

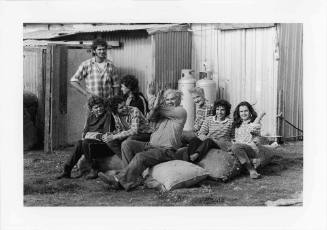

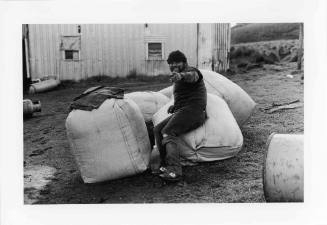

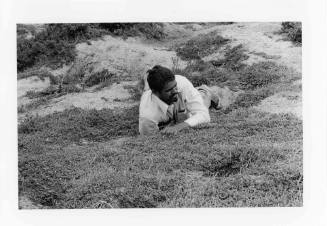

The Australian National Maritime Museum approached Ricky Mayanrd to chronicle the traditional practice of mutton birding by the Aborginal people of Bass Strait Tasmania. These photographs were taken in the Coorong area, Murray Lakes Region, South Australia, where mutton birding also takes place by the Ngarrindjeri People. The resulting series of black and white photographs became known as The Moonbird People. The photographs in the Australian Maritime Museum's Collection were chosen by Ricky because they show the different aspects to work and the different people in their tasks. Ricky has shown each person in their own landscape.

HistoryMutton birding is a traditional Aboriginal activity and revolves around the breeding season of several species of shearwater,one being the short tailed shearwater Puffinus tenuirostris.These sea birds migrate to Alaska in the Australian winter and return to south eastern Australia in the last week in September to breed, leaving again in April.They nest in enormous colonies, especially on offshore islands in Bass Strait and around theTasmanian coast. A healthy population can have as many as 6000 occupied burrows in one hectare.

Aboriginal islanders call the birds Moonbirds as they leave their nests at dawn to find food for their young and return at night as the moon is starting to rise. The term Mutton bird appears to have come into use at a nearly date among white settlers in the Southern Pacific. Use of the birds by Europeans in Australian waters began among shipwrecked mariners, and early in the 19thC the sealers developed mutton birding in to a substantial local industry. Originally, eggs, adults and chicks were taken in an indiscriminate fashion. A large trade was done in feathers for upholstery, in fat (for which the birds were rendered down in large pots), and in salt curing of young birds for food. In moden times the industry has been stabilised to harvest young birds only and for a limited season.This was necessary as the future of the industry had been in peril led by unwise exploitation. A number of rookeries are now protected on Flinders, Badger, Chappell & East Kangaroo Islands & a research program is being maintained on the population.

The birds are used for their meat, feathers and oil -

• oil from the stomach being used for pharmaceutical purposes.

• the body fat is rendered down for sale to dairy farmers as a feed subsidiaryfor

calves

• the down used for doonas & sleeping bags

• the meat is sold mainly in Tasmania and Victoria

An early European account of mutton birds was that of Matthew Flinders who commented on the flora and fauna in habiting the Furneaux Islands in 1798 on his voyage to rescue the survivors and cargo from theSydney Cove shipwreck on Preservation Island.

Another later account is of Englishman John Boultbee. His journal entries in late 1824 give us an insight in to the lives of Straits people at the time.

"On Preservation Island are several boat crews who go there to get a supply of mutton birds, which is a main article of their food. These birds, so called from the resemblance in flavour to mutton, are migratory. In September they come in flocks to the island, and remain, on or about the shore, until April, when they disappear.They burrow in the grounds like rabbits where they make holes to lay their eggs which are as large as a hen's egg. In the evening, when they swarm to their places, it is very easy to knock them down by dozens, merely by swinging a stick left and right. At daybreak they are to be heard making a deafening noise, as they proceed towards the seaside for the purpose of seeking their food. They are so numerous that I have seen a distance of 3 miles entirely covered by them. The size of these birds is equal to a common sized fowl.They are of a dark lead colour, & are a nourishing sort of food when eaten with poatatoes, to such constitutions as those who are inured to a life of hardiness. At a certain time of the year they grow lean which is the best time for plucking the feathers..."

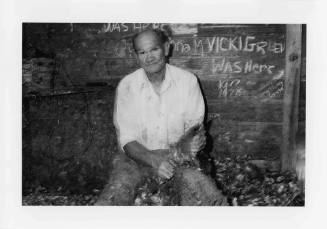

Current day practices are largely undertaken by the descendants of the early Straits people who own huts and processing sheds on the islands. These are built to a traditional pattern and are located close to boat loading places and the rookeries.

Each shed unit has accommodation and a processing building. An advance party goes to clean up the sheds and prepare the facilities-supplies are sent over by boat or small planes. The birds are caught by the "catchers" who work their way systematically through the rookeries. The catchers put an arm down the burrow, haul out the young bird and quickly break its neck. The bird is thent hreaded onto a long pole or spit which is carried over the shoulders. Care must be taken not to lose any oil from the birds. Up to 60 birds can be carried on the spit before the load is brought back for processing.

The oil is squeezed out of the bird into a barrel then the bird is passed through a window to the "pluck house" where the women pluck off the down then pass the bird through a hessian - guarded flap into the"scalding room".The legs are severed, usually by the children, then the birds are scalded for a few seconds.The remaining feathers arerubbed off then the bird is passed to then next room where they are cleaned and laid in racks to cool. Finally they are flattened out, packed in barrels with salt and brine.They are regularly flown out during the season to the mutton bird outlets. During World War 2 some of the birds were canned and sold as "squab in aspic". This does not seem to have survived. The hours are long and the work very skilled and physically hard. It is also very smelly and dirty and all work clothes are burnt at the close of the season. The mutton bird burrows are also home to tiger snakes - apparently the birders can tell by the temperature of the burrows whether a snake is in residence or not.

Working hours are 5.00am to 11.00 pm Monday to Saturday, Sunday is off and time for a get together with birders in the other huts and on the other islands - catching up with kith and kin.Significance"Every year between March and April, many Tasmanian Aborigines return to the Bass Strait Islands for the mutton bird season. This annual event, although a commercial enterprise, has great significance for Aboriginal people throughout the state.The season means belonging to a special community of family and friends who have their own shared identity which can be traced back to a time long before European settlement." (Ricky Maynard, photographer.)

![Untitled [Maree McLeod and Merlene Maynard]](/internal/media/dispatcher/105506/thumbnail)