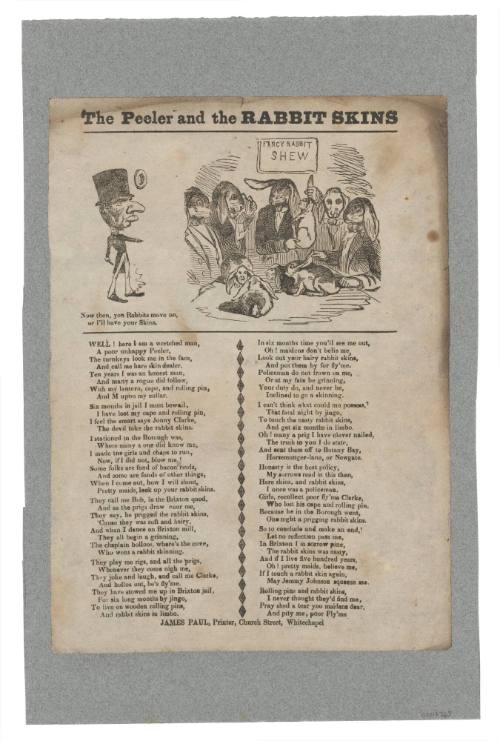

Broadsheet featuring the ballad 'The Peeler and his Rabbit Skins'

Printer

James Paul

Date1829 - 1850

Object number00017365

NameBroadsheet

MediumWoodcut engraving and printed text on paper mounted on card.

DimensionsOverall: 323 x 250 mm, 0.015 kg

ClassificationsEphemera

Credit LineANMM Collection

DescriptionThis broadsheet features the ballad "The Peeler and his rabbit skins". Below the title is a caricature of a policman in his uniform with the caption 'Now then, you rabbits move on, or I'll have your skins' and a cartoon of humanoid rabbits. The ballad is about a convicted Peeler (policeman) who is now in prison himself. He had been honest for ten years and had sent many criminals off to Botany Bay. James Paul, printer, Church Street, Whitechapel, London.HistoryThe Peeler and his Rabbits Skins

Well! Here I am wretched man,

A poor unhappy Peeler,

The turnkeys look me in the face,

And call me hare skin dealer.

Ten years I was an honest man,

And many a rogue did follow,

With my lantern, cape and rolling pin,

And M upon my collar.

Six months in jail I must bewail,

I have lost my cape and rolling pin,

I feel the smart says Johnny Clarke,

The devil take the rabbit skins.

I stationed in the Borough was,

Where many a one did know me,

I made the girls and chaps to run,

Now if I did not, blow me!

Some folks are fond of bacon rinds,

And some are fond of other things,

When I come out, how I will shout,

Pretty maids, look up your rabbit skins.

They call me Bob, in the Brixtonquadd,

And the prigs draw near me,

They say he prigged the rabbit skins

'Cause they was soft and hairy.

And when I dance on Brixton Mill, They all begin an grinning,

The chaplain holloos, where's the cove,

Who wen a rabbit skinning.

They play me rigs, and all the prigs,

Whenever they come nigh me, They joke and laugh, and call me Clarke,

And holloa out, he's fly me.

They have stowed me up in Brixton jail

For six long months by jingo,

To live on wooden rolling pins,

And rabbit skins in limbo.

In six months time you'll see me out,

Oh! maidens don't belis [sic] me,

Look out your hairy rabbit skins,

And put them by for fly’me.

Policeman do not frown on me,

Or my fate be grinning,

Your duty do, and never be,

Inclined to go a skinning.

I can't think what could me possess,

The fatal night by jingo,

To touch the nasty rabbit skins,

And get six months in limbo.

Oh! many a prig I have clever nailed,

The truth to you I do state,

And sent them off to Botany Bay,

Horsemonger-lane, or Newgate.

Honesty is the best policy,

My sorrows read in this then,

Hare skins, and rabbit skins,

I once was a policeman.

Girls, recollect poor fly‘me Clarke,

Who lost his cape and rolling pin,

Because he in the Borough went,

One night a prigging rabbit skins.

So to conclude and make an end,

Let no reflection pass me,

In Brixton I in sorrow pine,

The rabbit skins was nasty,

And if I live five hundred years,

Oh! pretty maids believe me!

If I touch a rabbit skin again,

May Jemmy Johnson squeeze me.

Rolling pins and rabbit skins,

I never thought they'd find me,

Pray shed a tear you maidens dear,

And pity me, poor Fly’ me.

Broadsheets or broadsides, as they were also known, were originally used to communicate official or royal decrees. They were printed on one side of paper and became a popular medium of communication between the 16th and 19th centuries in Europe, particularly Britain. They were able to be printed quickly and cheaply and were widely distributed in public spaces including churches, taverns and town squares. Their function expanded as they became used as a medium to galvanise political debate, hold public meetings and advertise products or cultural events.

The cheap nature of the broadside and its wide accessibility meant that its intended audience were often literate individuals but from varying social standings. The illiterate may have also had access to this literature as many of the ballads were designed to be read aloud. In 'Popular Culture in Seventeenth-Century England', Peter Burke notes that the golden age of the broadside ballad, between 1600 and 1700, saw ballads produced at a penny each which was the same price for admission to the theatre.

The ballads also covered a wide range of subject matter such as witchcraft, epic war battles, murder and maritime themes and events. They were suitably dramatic and often entertaining, but as James Sharpe notes, also in 'Popular Culture in Seventeenth-Century England', some of them were designed as elaborate cautionary tales for those contemplating a life of crime.

The broadside ballads in the museum's collection were issued by a range of London printers and publishers for sale on the streets by hawkers. They convey, often comically, stories about love, death, shipwrecks, convicts and pirates. Each ballad communicates a sense that these stories were designed to be read aloud for all to enjoy, whether it was at the local tavern or a private residence.SignificanceBroadsheets were designed as printed ephemera to be published and distributed rapidly. This also meant they were quickly disposed of with many of them not surviving the test of time. The museum's broadsheet collection is therefore a rare and valuable example of how maritime history was communicated to a wide audience, particularly in the 18th and 19th centuries. They vibrantly illustrate many of the themes and myths surrounding life at sea. Some of them also detail stories about transportation and migration.1930s-1940s

1790 - c 1870

Ryle & Company

1845 - 1849

James Catnach

1813 - 1838