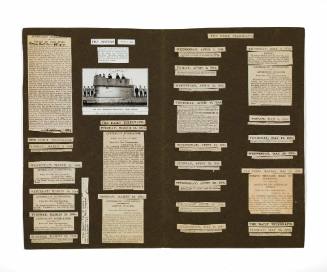

Newspaper report in old Turkish describing the torpedo boat SULTANHISAR's destruction of submarine AE2

Date1915

Object number00015948

NameNewspaper clipping

MediumInk on paper

DimensionsDisplay dimensions: 376 × 252 mm

ClassificationsEphemera

Credit LineANMM Collection Gift from Jennifer Smyth

DescriptionThis Turkish newspaper account of the sinking of AE2 by the torpedo boat SULTANHISAR was written by Captain Ali Riza Bey. It highlights the heroism of the Turkish defeat of the submarine by a much smaller vessel. This page is part of what must have been a series, possibly printed just after the war. In this section, Riza notes how he was ordered back to Istanbul but decided to have one last sweep of the area he had last seen AE2. He vivdly describes sighting AE2 and closing in to try and torpedo or ram the submarine. Riza Bey wrote; ‘Cannons and torpedos were ready, the engines were working at full power and the underdog, SULTANHISAR, was taunting the opponent, like a hawk that was to hunt its prey’. Riza Bey was to later publish his own account of events in a book titled 'How I sank the AE2 submarine in Marmara Sea'.

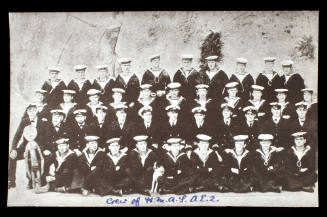

HistoryWhen war began in August 1914 the RAN submarines AE1 and AE2 were sent with the Australian naval forces attacking German-held colonies in New Guinea and other Pacific islands. Stoker Petty Officer Henry (Harry) James Elly Kinder had initially been assigned to AE1 but due to ‘marriage leave’ ended up on AE2 – a fortunate turn of fate. Kinder wrote:

'On 14th September, 1914, AE1 went out, accompanied by a destroyer, on what was to be her last journey. Little we thought, when laughing and joking with the crew just before she left, that it was the last time that we were going to see them'.

AE1 was on a routine patrol and did not return. It was lost with all hands off the coast of Rabaul, New Guinea, and has never been located.

After the German Pacific colonies were quickly taken by the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force, AE2 was directed to the Mediterranean where a grand naval assault was planned on the Dardanelles Strait prior to the Gallipoli Campaign – a campaign that might not be needed if the Allied fleet managed to break through the heavily mined and fortified strait.

But this assault on 8 March failed and the Turkish celebrated a great victory against the might of Britain, as they still do each year on that date. Concealed minefields destroyed several Allied ships. Kinder recalled:

'…it wasn’t a bad day’s work for the Turks although they too suffered as a lot of their forts were blown up. It showed that the forcing of the Dardanelles wasn’t going to be an easy job as it was well fortified by land and water'.

The job of forcing the straits was given over to submarines. Just as the Gallipoli landings on 25 April were about to commence, AE2 was tasked with trying to get through to create havoc among Turkish shipping in the Sea of Marmara and assist with delaying reinforcements from eastern Turkey crossing to the Gallipoli peninsula.

The dangers were immense. Several submarine attempts had already failed, and AE2’s first effort on 24 April met the same fate. Kinder wrote:

'One of the knuckle joints on the driving shaft snapped. This block is a 4 inch square piece of steel which prevents the hydroplane from moving in a rough sea or when running on engine power. The slightest incline would drive the boat under and then there would be another submarine disaster. What the captain said when he heard the extent of the damage would fill a book but I doubt if it would be readable'.

But with running repairs, AE2 tried again the next day. Kinder noted that every submarine had a motto: ‘AE2’s was “Fortuna Favet Fortibus” or “Fortune Favours the Brave”. With a motto like that we ought to have some kind of luck.’

In the early hours of 25 April, just as Anzac troops were moving from ships into landing barges, AE2 crept into the Dardanelles Strait. Kinder described the beginning of the voyage:

'The captain ordered the boat to be taken to 80ft [24 metres] so as to be well clear of any shipping or floating mines which float about eight or nine feet under the water. Our greatest danger was running onto banks or getting entangled in wire hawsers. Everything was very quiet for the first two hours and only an occasional order from the captain and the hum of the motors broke the stillness. Strict silence is maintained by the crew so that no order is missed.

The captain, every twenty minutes or so, brought the boat up to the 22ft [7 metre] mark to take observations through the periscopes and see that we were on the right course; then down again to 80ft, well out of sight.

At 6am the captain remarked that the next few minutes might see us sailing off for Kingdom Come after our halos and wings. We were approaching the place marked on the chart where there were two stationary mine fields, each containing nine rows of mines. Mines are one of the most dreaded things in submarines. It was not pleasant to know that we had to face eighteen rows of them'.

Just after 6am AE2 scraped the first wire. Kinder recalled that ‘it was enough to stop one’s heart beating to hear it sliding over the steel deck’. He kept count of the wires as the boat hit them and ‘on the eighteenth we guessed we had passed through our first danger’.

The next thing was to pass the ‘narrows’ with its swift current, banks, shallows and overlooking forts. It was here that the British submarine E15 had ‘met her fate’ a few days before.

At this point, the captain of AE2, Commander Henry Stoker, saw several Turkish cruisers at anchor and decided to ‘have a shot’. Kinder wrote:

'The bow torpedo tube was got ready but just as the torpedo was discharged a mine layer steamed across the cruiser’s bows and got in our line of fire. Unfortunately for her, she stopped the torpedo. It must have been an unpleasant surprise for them so early in the morning. As soon as the torpedo was fired the captain ordered the sub down to 80ft to get away from the hornets’ nest we had stirred up on top'.

But the discharge of the torpedo had affected the vessel’s compass and AE2 was 80 feet under water and running blind. Surfacing to gain bearings was too dangerous, as they were in front of the Turkish forts, but the narrows forced their hand – as the bottom was felt, AE2 rose but became stuck on a bank and surfaced right under Turkish guns.

Kinder noted that in one sense they were fortunate, being so close inshore that the forts’ guns could not be successfully trained on them. With all the ballast tanks blown and the motor full speed astern, gradually AE2 bumped off the bank. The tanks were again flooded and slowly the vessel sank back down to 80 feet.

To Kinder, it had seemed AE2 had been on the surface an hour rather than just a few minutes. ‘At ordinary times I didn’t care to be down under water but I was thankful to see the gauge registering 80ft once more’.

Yet after escaping one side, and still travelling blind, AE2 careened into the opposite bank – again forcing its way off and gaining bearings before Turkish gunfire could target it. Their luck continued as the compass ‘became sensible again’ and Commander Stoker continued towards their goal of the more open Sea of Marmara.

AE2 had indeed stirred up a hornets’ nest. With an array of Turkish vessels desperately searching for it, Stoker decided to rest the vessel on the bottom. It was 8 am on Sunday morning. The crew had breakfast and some sleep, then rose for morning prayers at 11 am. Kinder wrote, ‘I dare say it was the first time prayers were read on the bottom of the sea.’

Commander Stoker decided to wait for nightfall so they might surface with less risk. Turkish vessels dragged lines searching for the submarine throughout the day. A destroyer passed only a few feet over their position – so close the AE2 crew could ‘hear the stokers opening the furnace door and shovelling coal into the fires’. Kinder continued:

'There was no more sleep for us as it got on our nerves to hear the boat persistently going backwards and forwards. Once the drag hit the boat and for one awful moment we waited anxiously to see if the destroyer would stop but when we heard her continue on her way we knew the drag had not caught. If the drag had held it would have been the end of AE2 and her crew as a depth charge would most likely have been our fate'.

Towards the end of the day the air inside the submarine was ‘getting thick’. AE2 had been submerged for 14 hours and carried no oxygen to renew the air.

At 10.30 pm Commander Stoker decided it was quiet enough above to continue. For Kinder, ‘action was far better than lying on the bottom imagining all sorts of things happening’. When the vessel surfaced after 18 hours submerged, the crew were joyous. ‘What a relief it was … How nice that fresh air tasted.’

After sitting on the surface and recharging batteries, finally, at daylight on 26 April, AE2 headed into the Sea of Marmara and a sense of security, with open water to escape in. Kinder recorded the moment:

'It was a beautiful day and the Sea of Marmara was like a sheet of glass … it was lovely to sit on the saddle tanks in the sunshine … We seemed to have the Sea of Marmara to ourselves'.

Now, out of the dangers of the narrows, mines, current, forts and depth charges, AE2 was in the box seat – brazenly travelling on the surface scaring off local shipping and turning back transports with enemy troops heading towards Gallipoli. Stoker had been ordered to ‘run amuck’ [sic] if he made it through.

After spending the next night submerged, then scaring off several more transports the next day, Stoker saw an opportunity and fired a torpedo at a transport vessel. Its escorting destroyers then attempted to ram AE2 and as the submarine dived, a destroyer’s propellers sounded so close that ‘we ducked our heads to allow it to pass’.

Another night was spent lying on the bottom. Kinder reflected that:

'When the boat is lying on the bottom with only a pilot light on, one begins to imagine all sorts of things happening… Perhaps it would not be able to rise again with the crew caught like rats in a trap with no hope of escape. If you let your imagination run too long you can feel your hair rising … Sometimes the sound of a voice is a welcome sound'.

Then on 29 April, in a moment of utter surprise and almost disbelief, a British submarine was spotted. E14 had also run the gauntlet in AE2’s wake. The two commanders then agreed to separate and rendezvous the next day.

But this meeting was not to occur. The next day, on nearing the appointed rendezvous,two Turkish gunboats and a destroyer were sighted making a bee-line for AE2. When the vessel dived, something was wrong – the boat started to go down by the bow. It was impossible to stand; ‘everything moveable in the boat started to slide and roll to the bows’.

Eventually, after all the ballast tanks were blown and with the engines full astern, AE2 began to rise. But circling above were Turkish warships. AE2 surfaced with a ‘whoosh’ and Stoker quickly flooded the tanks in order to dive again, hoping this time to dive correctly. But luck had seemed to finally desert AE2.

Just as it was about to submerge, three shells hit the vessel. Water was flooding the engine room. AE2 descended and after a hard struggle, the watertight doors to the engine room were closed. The vessel went down to 80 feet and then stopped. Would the flooded engines keep going? Without them AE2 could not surface. Kinder recalled;

'Many things flashed through my mind in those few minutes. I could picture AE1 and her crew under similar conditions fighting for their lives with all the boat in disorder. Although they couldn’t have lived long … and the boat’s hull would soon have been crushed under the enormous pressure … Still, they must have suffered agonies in those few seconds. We would be lucky if we did not share the same fate'.

Then AE2 began to rise. Perhaps luck was still with them. But on the surface the crew soon realised AE2’s end had come. While Stoker gave the order to abandon ship, the two gunboats were still firing and shells were falling all around.

Henry Kinder spent his last few minutes looking around the boat. He noticed the clock at five minutes to 12, and recalled there was a rabbit pie in the oven. He left the pie and went to his ditty box to retrieve 16 shillings and a photograph of his wife.

On deck, Kinder saw Commander Stoker come up after opening the kingston valves to scuttle the vessel. They then dived overboard with the rest of the crew. For a few seconds Kinder saw AE2 ‘moving through the water like a big, wounded fish, gradually disappearing from sight’.

There was only one casualty – a large rat that the cat at Garden Island in Sydney had chased on board one morning when the submarine was lying alongside. The rat took up residence in the engine room and the crew fed him to stop him eating their own food.

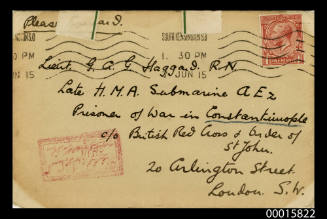

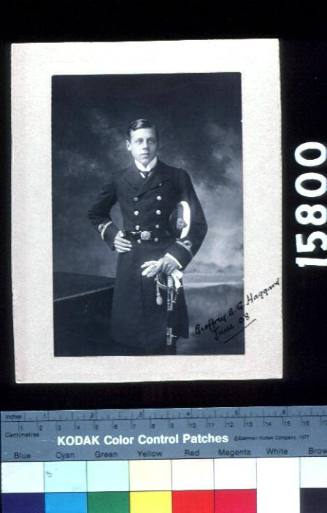

In what Commander Stoker agreed was a surreal moment, Kinder noticed that Lieutenant Haggard had lit a cigar just before leaving the boat and he recalled that Haggard looked rather comical floating around amid clouds of smoke. Stoker remembered a different moment:

'Curious incidents impress one at such times. As those last six men took [to] the water the neat dive of one of the engine-room ratings will remain pictured in my mind forever'.

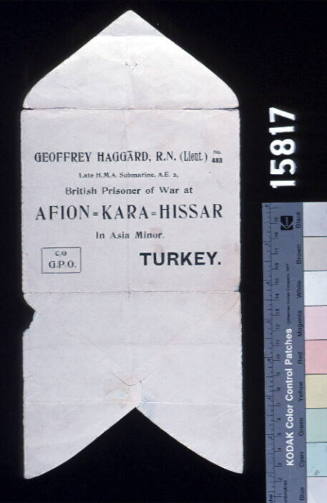

The Turkish torpedo boat SULTANHISAR under Captain Ali Riza Bey took the crew prisoner. They remained in captivity for the rest of the war. Riza Bey later wrote his own version of events in his book 'How I sank the AE2 submarine in Marmara Sea'.

Henry Kinder recounted much of his time in the camps in his memoir, but said ‘there were many incidents that happened during the time that we were prisoners that I will not be able to write down here’.

He apparently never spoke about these events after the war. Kinder returned to Australia a broken man, having suffered kidney damage, malaria and severe beatings in the camps. He left the RAN in 1919 and moved with his wife to Dorrigo and then Casino in northern New South Wales. In later life he moved to Evans Head where he apparently became increasingly eccentric and entertained the locals by making large beach-sand drawings and sculptures. His artistic nature was still with him. Henry Kinder died on 25 April 1964 – Anzac Day.

Lieutenant Geoffrey Haggard kept a ‘black book of notes’ after the war, though he never published them. According to his daughter, Haggard remained deeply troubled by the events of 1915. AE2 sent a wireless signal through to say the vessel had breached the Dardanelles Strait, and it has been argued that this news had a role in firming the Allied commanders’ resolve to continue the Gallipoli invasion, rather than evacuate in the early stages. The resulting carnage haunted Haggard for the rest of his life, resulting in a long personal silence for this crew member of submarine AE2, the so-called ‘Silent Anzac’.

See Stephen Gapps 'Reading prayers at the bottom of the sea' http://wp.me/phJZE-3AH

Further reading

Fred and Elizabeth Brenchley, Stoker’s Submarine – Australia’s daring raid on the Dardanelles on the day of the Gallipoli landings, Australian Teachers of Media, St Kilda, Victoria, 2001, 2013

Henry Hugh Gordon Stoker, Straws in the Wind, Herbert Jenkins, London, 1925

Jennifer Smyth, The Long Silence – The story of G A G Haggard of Submarine AE2, Spectra Litho, Toorak, Victoria, 2007

SignificanceLieutenant Haggard, his Commander Henry Stoker and the rest of the crew from the submarine AE2 were picked up by the Turkish boat SULTAN HISSAR after scuttling their submarine on 30 Aptril 1915 in the Sea of Marmora. The whole crew then spent the next 3 1/2 years as prisoners of war throughout Turkey and four crew members later died as a result of illness due to the harsh conditions experienced.