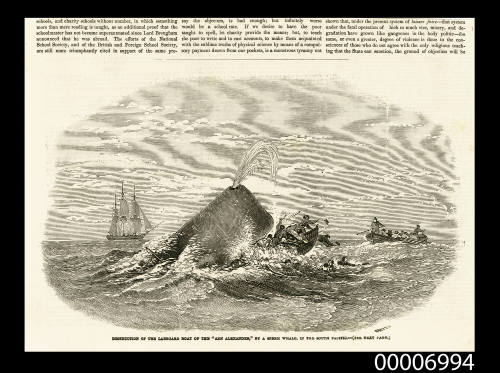

Destruction of the larboard boat of the ANN ALEXANDER by a sperm whale in the South Pacific

Maker

Illustrated London News

(Established 1842)

Date1851

Object number00006994

NameEngraving

MediumInk on paper

DimensionsOverall: 192 x 281 mm

ClassificationsEphemera

Credit LineANMM Collection

Collections