SMS EMDEN

Date1908-1914

Object number00005571

NameCap tally

MediumTextile, silk or cotton

ClassificationsClothing and personal items

Credit LineANMM Collection

DescriptionThis item is a cap tally band from the German World War One Light Cruiser 'SMS EMDEN', launched on 26 May, 1908. Leaving Tsingtao in July, 1914, EMDEN learnt of the declaration of war while at sea. Under the command of Lieutenant Commander Karl von Müller EMDEN took on the role of a 'surface raider', destroying or commandeering a large number of Allied merchant vessels in the Indian and Pacific oceans whilst attempting to avoid enemy warships which would have been able to outmatch this three-funnelled Light Cruiser's limited firepower. On 9 November, 1914, however, EMDEN was forced to engage HMAS SYDNEY in what has subsequently been called the 'Battle of Cocos.' EMDEN was wrecked, with the result that cap tallies such as this one were aquired as souvernirs by the crew of the SYDNEY. There are still a number of them in circulation.HistoryEMDEN's Naval Uniforms:

German naval officers serving in the tropics in 1914 usually wore a white cap with black hatband, black leather peak and black chinstrap. On the front of the cap would have been a yellow metallic embroidered badge, consisting of an imperial crown above an imperial cockade. A scroll beneath the crown indicated a 'junior' officer, while a laurel wreath around the cockade indicated a 'senior' officer.

This cap would have been worn with a matching white tunic, trousers and shoes. The tunic had a standing collar, plain cuffs, no pockets and six yellow metal buttons down the front. Rank insignia would have been displayed on the shoulder straps. This was a far simpler uniform than would have been worn by German naval officers serving in cold climates. Here the uniform would have consisted of a dark blue naval cap and a blue double-breasted tunic with a white shirt and black tie underneath. The tunic had six buttons running down either side and was usually worn open at the collar. Rank insignia would have been displayed as yellow metallic bars on the cuff below an imperial crown, while additional clothing would have consisted of matching blue trousers and black shoes.

Officers who went ashore as part of a landing party in the tropics (such as Lieutenant Captain Hellmuth von Mücke in the case of SMS EMDEN) would have worn a white naval tropical helmet, with an imperial cockade, and a khaki naval officers' uniform with rank indicated by braided shoulder straps. They would have been armed with a Luger naval pistol and had a distinctive ammunition pouch worn on a Sam brown style belt. Ceremonial items such as swords and a neat shirt and tie worn underneath could also be worn, although they were often deemed impractical.

The uniforms worn by other ranks in the Imperial German Navy in 1914 were similar to those worn by every other European navy during this period. Blue uniforms were usually worn in cold climates while white uniforms were worn in hot climates (although clothing items were sometimes mixed and mismatched on less formal occasions). Headdress consisted of a peak-less naval cap either in white or dark blue. It bore a small imperial cockade above a black cap tally (exactly the same as this item). On the tally was the name of the ship or unit the sailor was attached to.

There were three different types of naval shirt (a blue woolen shirt, a white shirt and a 'working' shirt) together with two types of jacket (a blue double-breasted jacket and a blue dress jacket). Trousers were either dark blue wool of light-weight white and were usually worn loose over short black leather jackboots. NCO rank insignia was usually worn in the form of chevrons on the left sleeve (blue on white uniforms, or yellow/white on dark blue uniforms), whilst specialist insignia was worn in the form of oval patches on the upper left sleeve bearing symbols of their trade (again, blue on white uniforms and yellow/white on dark blue uniforms).

The white cotton shirt, which would have been the clothing of choice for German sailors serving in the tropics, had blue cuffs with two white stripes around the pointed upper edge, and a single white stripe along the lower edge. The naval collar of this shirt was in a darker shade of blue with three white stripes around its edges and was sewn into the shirt. Under this collar was worn a black neckerchief with a white tie. A simpler white shirt known as the 'working' shirt was worn when undertaking manual labour in a warmer climate. It was made of lightweight cotton with plain cuffs and a single right breast pocket with no pocket flap. It had a simplified sewn-in naval collar in pale blue, again with three white stripes around the edge. Under this collar was usually worn a black neckerchief with a white tie.

Sailors going ashore in a landing party in the tropics usually wore a naval tropical helmet, the white 'working' shirt and white trousers, together with canvas gaiters over ankle boots. Often the shirts were either issued in an 'off-white' colour or were dyed khaki using tea. They would have worn 'Y' bracing, with a bread bag and a bayonet hanging from the belt.

HISTORY OF THE EMDEN:

SMS EMDEN was a German light cruiser, launched on 26 May 1908, and commissioned into the German Imperial Navy on 10 July 1909. As a light cruiser she was designed, not to fight other warships, but to disrupt merchant shipping; she was armed with ten 4.1inch (105mm) guns and was the last German cruiser to be equipped with reciprocating engines (subsequent vessels were equipped with steam turbines). Like most ships of the time, the EMDEN's twelve boilers were heated by burning coal, which had to be constantly shoveled into the fireboxes manually by stokers.

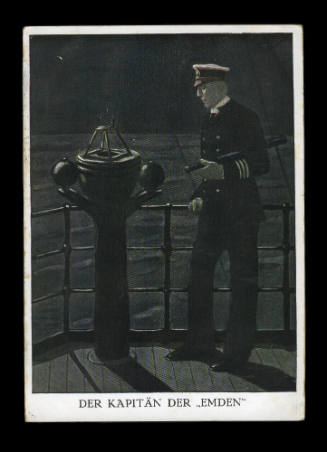

On 31 July 1914 SMS EMDEN left Tsingtao (a German colony between 1898 and 1914 that is now known as 'Qingdao' and is a port in Shandong Province, China). She was at sea when she learnt of the outbreak of war on 2 August 1914. She was captained by Lieutenant Commander Karl von Müller, a shy and withdrawn man who was, nevertheless, regarded with great reverence by his crew. He spent most of his time on the bridge and comfortable chairs were placed there for him to sleep and rest in between action and emergencies. He maintained a constant state of readiness aboard his ship, adding extra lookouts after darkness and ordering gun and torpedo crews to be stationed at their posts around the clock.

It took EMDEN some time to reach its desired destination in the Indian Ocean and once there her fighting career was short, lasting barely two months. On 10 September 1914 she captured her first prize; on 9 November the cruiser was a wreck on the shoals of Cocos Island (now part of the Australian territory known as the 'Keeling' or 'Cocos' Islands in the Indian Ocean; halfway between Australia and Sri Lanka). Her first prize, the Greek steamer PONTOPOROS, though an officially neutral ship, was ferrying Allied coal supplies to India. To solve the dilemma von Müller persuaded the Greek captain that German money was just as good as British and that he should now consider himself under charter to the German Government. The PONTOPOROS, together with the EMDEN's stalwart collier (a naval coal transport) the MARKOMANNIA would stay in regular contact with EMDEN until 12 October 1914 when the former ship was captured and the latter sunk by the British Town class light cruiser HMS YARMOUTH.

Although its fighting career was relatively short-lived, the EMDEN quickly built up a fearsome reputation in and around the Indian Ocean's shipping lanes. The ship's chief officer Lieutenant Captain Hellmuth von Mücke arranged for the ship to be disguised by fashioning a false funnel out of sail-cloth canvas and bamboo stakes that was capable of spewing chemically-produced smoke when necessary. Whereas the German cruiser only had three funnels, British cruisers had four and the EMDEN was now able to pass itself off as the YARMOUTH which was also known to be in the area. It was a ruse that proved effective time and time again. On 10 September 1914 the 4000 ton passenger-cargo ship INDUS was captured and sunk en route from Calcutta to Bombay; the 6000 ton LOVAT suffered the same fate not long after.

All in all the EMDEN successfully captured and/or sunk around twenty seven ships during its wartime service. The crew often had the luxury of enjoying many of the spoils of their raids and the prisoners they took, as was the case for most German surface vessels during the war, were treated well and usually ended up being set free. Von Müller was under no illusions, however, as to the fait which awaited his ill-equipped raider; the run of luck he had was nothing short of miraculous, but it had earned the ship a reputation meaning that a confrontation with another warship at some point was inevitable. The world was reading daily reports of his exploits and by late September there were known to be seven British ships, three Japanese vessels and an old Russian cruiser combing the Indian Ocean in search of the EMDEN. It is a testament to the German ship together with the ability of its officers (which included the Kaiser's nephew, Prinz Franz Joseph of Hohenzollern as second torpedo officer) that it was, in actual fact, an Australian ship that would eventually corner and sink EMDEN over a month later.

HMAS SYDNEY was a Chatham class light cruiser of the Australian Royal Navy. It was launched on 29 August 1912 and commissioned on 26 June 1913 at Portsmouth, England.

Following the outbreak of World War One on 4 August, 1914, SYDNEY was stationed in New Guinea and Pacific waters, taking part in the brief campaign to capture Germany's Pacific colonies. Highlights during this period included the capture of Rabaul (a township and headquarters of German New Guinea) and the destruction of Angaur Island Wireless Station, both in September 1914. In October, SYDNEY and her sister ship HMAS MELBOURNE detached from the Flagship HMAS AUSTRALIA to return to Australia. They were to form part of a unit assigned to escorting the first ANZAC convoy across the Pacific and into the Indian Ocean. The convoy consisted of SYDNEY, MELBOURNE, HMAS MINOTAUR and the Japanese cruiser IBUKI, together with thirty-eight transports. It set sail from Albany, Western Australia, on 1 November, 1914 and was timed to pass some fifty miles east of the Cocos Islands on the morning of 9 November, 1914.

Direction Island is part of the Cocos Island group in the Indian Ocean. In 1914 it was managed by the Eastern Extension Telegraph Company which had built a relay station there and from the Cocos the submarine cables ran to Weltevreden in the Dutch East Indies, to Perth in Australia and to Rodriguez Island near Mauritius and thence to Africa. During wartime its strategic importance was immense and it was for this reason that on 9 November 1914 the Emden was sighted off the island. Von Müller's primary objective was to disrupt British communications, although he also planned to harry shipping coming out of Western Australian ports and to create the same sense of dislocation which he had managed in the Bay of Bengal when essential supplies were held in ports for fear of the EMDEN. What the German captain was unaware of, however, was that when he reached the Cocos Islands he had passed within eighty-eight kilometers of the ANZAC convoy. Supposing the coast to be clear, he ordered von Mücke to take a party of fifty men ashore to destroy the cable and wireless stations and, if possible, to cut the cables.

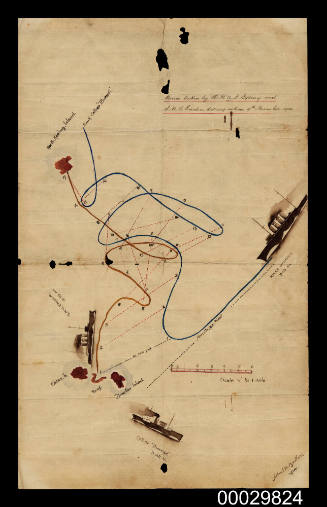

At around 6.20am, wireless telegraphy operators aboard several transports as well as the warships of the ANZAC convoy picked up the message 'Kativ Battav', followed from a query from the Cocos Island Wireless Station asking 'What is that code?' The EMDEN was signaling her collier BURESK to rendezvous with her at Point Refuge. Shortly afterwards Cocos sent out a distress signal that read 'Strange warship approaching.' Although the Emden attempted to jam the signal with its powerful Telefunken equipment, the close proximity of the ANZAC convoy meant it was able to get through the interference and it was shortly followed by 'SOS, Emden here.' After some argument over which ship should break away from the convoy to engage the EMDEN it was decided that the SYDNEY was on the side that was closest to the Cocos Islands and it was capable of doing at least three knots more than the Japanese heavy battle cruiser IBUKI. By 7am SYDNEY was 'away doing twenty knots' and at 9.15am the island, together with the EMDEN were spotted some seven or eight miles distant.

When the SYDNEY arrived von Mücke's wireless-wreckers had already been ashore for some time. They had met with little resistance and had posted men to each of the buildings. The key operator had continued to send out messages right up until the moment he was captured and the last words that went down the cables were 'They are entering the door.' The staff were assembled and placed under guard, while all the papers from the wireless hut were collected for transport back to the EMDEN. The wireless and cable equipment was destroyed by axe and by hand, tables and chairs were overturned and holes were drilled in the base of the wireless mast into which dynamite was placed. After the mast came down, the Germans turned to destroying the engine room, the switchboards and even the seismograph. They attempted to cut the cables, although work was abandoned when siren blasts were heard from the EMDEN recalling the landing party. Having sighted the SYDNEY, the German ship was already busy working up steam and preparing to get under way.

The events which subsequently unfolded have been referred to as the 'Battle of Cocos.' Despite the EMDEN's reputation within the German Imperial Navy for the speed and accuracy of her gunnery, her 105mm guns were simply outmatched by the SYDNEY's 150mm armament. The former began to fire at an impressive rate of one salvo every six seconds, when the latter was still ten kilometers away; this meant she had three salvos in the air at any one time. One drawback of this, however, was that the elevation of her guns was at thirty degrees, meaning that her shells took longer to reach the target than the SYDNEY's which, because of her larger caliber guns, was able to fire the same distance at a lower elevation. Furthermore, the SYDNEY's armour plating was less vulnerable at long range than the EMDEN's.

The battle lasted an hour and a half. The EMDEN's first salvo was ranged along an extended line but every shot fell within two hundred yards of the SYDNEY. The next salvo was on target and for the next ten minutes the Australian cruiser came under heavy fire. Fifteen hits were recorded but fortunately 'only five burst.' Four ratings were killed and several wounded. When the EMDEN's guns were finally silenced von Müller decided to run the ship aground on North Keeling Island in a bid to save his crew members who were still alive. The captain of the SYDNEY estimated that he had scored around a hundred hits on the EMDEN by the time it ran aground. 134 of the Emden's crew were killed in the battle. While some of the survivors were sent to Australian POW camps, the majority, including Müller were imprisoned on Malta.

The EMDEN, wrecked but still somewhat intact, was left to disintegrate on North Keeling Island, until a visitor to the Cocos group in 1919 reported that almost all traces of the ship had disappeared. It is interesting to note that von Mücke's landing party never made it back to the EMDEN and, making off in the schooner AYESHA, managed to escape back to Germany after a series of harrowing adventures!

SignificanceThis item is of immense significance in that it represents one of the few surviving traces of the World War One Light Cruiser 'SMS EMDEN' which was wrecked off North Keeling Island after an engagement with HMAS Sydney in November, 1914. The vessel subsequently disintegrated and it is for this reason that this tally band becomes an important source in documenting the history and existence of this famous warship.