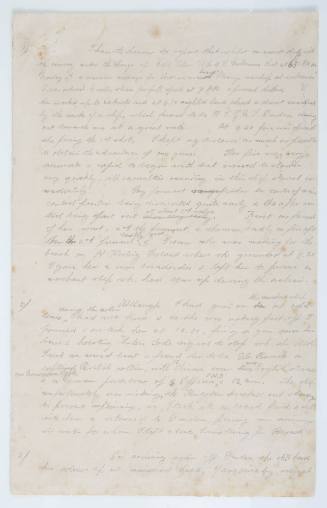

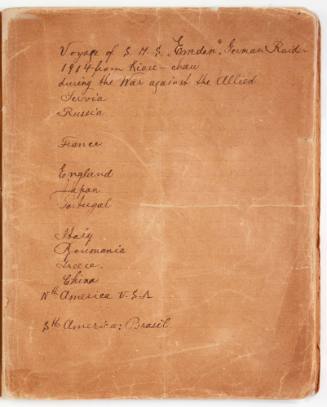

Captain Glossip's Report in his own handwriting of the action between HMAS SYDNEY and SMS EMDEN on 9 November 1914

Date1914

Object number00000444

NameEnvelope

MediumPaper

DimensionsOverall: 302 x 405 mm

ClassificationsEphemera

Credit LineANMM Collection

DescriptionThe envelope which contained the handwritten draft of the report of the successful action by HMAS SYDNEY against SMS EMDEN written by Captain Glossop.HistoryHMAS SYDNEY was a Chatham Class Light Cruiser built by the London-Glasgow Shipbuilding Company, Scotland. She was laid down in February, 1911 and launched on 29 August, 1912 by Lady Henderson, wife of Admiral Sir Reginald Henderson.

Joining the battlecruiser HMAS AUSTRALIA at Portsmouth, SYDNEY was commissioned on 26 June, 1913. The two vessels then sailed for Australia in July, 1913 via St. Helena, Capetown and Mauritius, eventually making landfall at Albany, Western Australia for coaling on 19 September, 1913. In order to make their arrival all the more momentous the two ships were ordered to avoid major ports, travelling straight to Jervis Bay where the remainder of the the main Australian fleet, HMAS MELBOURNE, HMAS ENCOUNTER, and three newly built destroyers were at anchor. The fleet then sailed north on the short voyage to Sydney arriving in October, 1913.

SYDNEY had been commissioned under the command of Captain John C. T. Glossop (1871-1934). The vessel's displacement was 5,400 tons, whilst her armament would ultimately consist of eight six-inch guns, one 13-pounder gun, four 3-pounder guns and two torpedo tubes. She was the sister ship to HMAS MELBOURNE and HMAS BRISBANE, having been completed second respectively. The 'Chatham Class' was a subclass to the 'Town Class' light cruisers of the Royal Navy. Known to Australians simply as the 'Sydney' Class, the 'Chatham Class' differed from other subcategories of the Town Class by having reduced deck armour in order to incorperate newly developed belt armour. Their six-inch guns were mounted in single turrets with no secondary armament other than her anti-aircraft weaponary that would be further increased during the First World War. The Chatham Class also had aircraft fitted during the War.

Following a period spent in eastern Australian ports, SYDNEY proceeded to Singapore in March, 1914, to act as escort to the two new Royal Australian Navy submarines AE1 and AE2. Although the two submarines had managed to reach Singapore with comparatively little trouble, the next stage of the voyage to Australia would make up for this lack of incident. Soon after leaving port AE1 lost all power and SYDNEY was forced to take her in tow while repairs were carried out. In fierce currents the tow rope parted and AE1 was nearly rammed by AE2, which had to take drastic evasive action. As a result of this the helm of AE2 was found to be jammed and the two submarines were drifting helplessly out of control. SYDNEY had to cope with the situation but found that she herself was out of action as the parted tow rope had twisted itself around her rudder rendering the vessel immoveable. When going to the submarines' rescue she was unable to turn and very nearly rammed them.

Captain Glossop ordered all three vessels to anchor until morning when a diver was put over to free the SYDNEY's rudder. AE1 was taken in tow once more and the flotilla got underway bound for Darwin. The flotilla entered Sydney harbour on the 24 May, 1914, where they were welcomed by the entire Australian fleet. SYDNEY spent the remainder of the pre-war months in Australian waters.

On 3 August, 1914, SYDNEY was joined at Townsville, Queensland, by the destroyers HMAS WARREGO and HMAS YARRA before proceeding north to form a unit in Admiral Patey's Pacific Squadron. Following the outbreak of war the following day, SYDNEY operated in New Guinea and Pacific waters, taking part in the brief Allied campaign against the German Pacific posessions and carrying out a series of punative patrols. Highlights during this period included the capture of Rabaul (the capital of German New Guinea) between 9 and 11 September, 1914 and the destruction of the Angaur Island (now part of Palau) Wireless Station on 26 September, 1914.

In October, 1914, SYDNEY and her sister ship MELBOURNE detatched from the Flagship HMAS AUSTRALIA and returned to Australia to form part of the escort for the first ANZAC convoy, which consisted of thirty eight transports carrying 20, 000 men and 7,500 horses. The escort consisted of SYDNEY, MELBOURNE, the British armoured cruiser HMS MINOTAUR and the Japanese battlecruiser IBUKI. The convoy left Albany, Western Australia on 1 November, 1914, bound for the Middle East. It was timed to pass some fifty miles east of the Cocos Islands on the morning of 9 November, 1914.

At 0620 on 9 November, wireless telegraphy operators in several transports and in the warships picked up signals in an unknown code, followed by a query from the Cocos Island Wireless Telegraphy Station asking 'What is that code?' It was, in fact, the German cruiser SMS EMDEN ordering her collier BURESK to join her at Point (sometimes called 'Port') Refuge (part of the Cocos Island Group). After some debate between the vessels over which of the escorts should be dispatched, it was decided that SYDNEY, as the warship nearest to Cocos, should be sent. Detatching itself from the convoy at 0700 SYDNEY was able to exceed her designed speed, arriving at Cocos at 0915 and spotting EMDEN some seven or eight miles distant. At a range of 10, 500 yards EMDEN opened fire and SYDNEY was soon under heavy fire. SYDNEY was, however, faster and better armed than her German opponent and by 1115 EMDEN lay wrecked on North Keeling Island, although it continued to resist. SYDNEY then left the scene to persue the BURESK and, having forced the collier to be scuttled by its crew, returned at 1300 to secure EMDEN's surrender. Four members of SYDNEY's crew had been killed, whilst twelve had been wounded.

On 15 November, 1914, SYDNEY arrived in Colombo, Sri Lanka, and from there was ordered to proceed to Malta where she arrived on 3 December. She was then ordered to Bermuda to join the North American and West Indies Stations for patrol duty. For the next eighteen months SYDNEY was engaged in observing neutral ports in the Americas, mainly in the West Indies with Jamaica as a base and off Long Island with Halifax as a base and Squadron Headquarters at Bermuda. SYDNEY finally left Bermuda on 9 September, 1916, arriving in Devonport, England, on 19 September, and from there proceeded to Greenock, Scotland for refit.

On 31 October, 1916, SYDNEY was temporarily attached to the 5TH BATTLE SQUADRON at Scapa Flow, Scotland. On 15 November, she sailed for Rosyth, Scotland, whereupon she joined the 2ND LIGHT CRUISER SQUADRON, consisting of the four sister ships HMS SOUTHAMPTON, HMS DUBLIN, HMAS MELBOURNE and HMAS SYDNEY, attached to the 2ND BATTLE SQUADRON of which HMAS AUSTRALIA was flagship. For the remainder of the War SYDNEY's duties were confined to routine North Sea patrols.

On 4 May, 1917, while on patrol between the Humber Estuary and the mouth of the Firth, SYDNEY fought a running engagement with the German zeppelin L43. After both combatants had expended all of their ammunition to no avail they reportedly parted company on good terms. In August, SYDNEY commenced a three month refit at Chatham, England, during which she aquired the tripod mast that is now sited at Bradleys Head, Sydney. Of greater significance, however, was the fact that she was fitted with the first revolving aircraft launching platform to be installed onboard a warship.

On arrival at Scapa Flow in December, 1917, SYDNEY's commanding officer, Captain J. S. Dumaresq (who took over from Glossop earlier in the year on 5 February) borrowed a Sopwith Pup that was then being operated from a fixed platform onboard HMS DUBLIN. On 8 December the aircraft was successfully launched from the SYDNEY's platform in a fixed position. It was the first aircraft to take off from an Australian warship. Nine days later the Pup flew off the platform while it was turned into the wind; the first time an aircraft had been launched from such a platform in a revolved position. Early in 1918, SYDNEY took onboard a Sopwith Camel as a replacement for the Sopwith Pup.

On 1 June, 1918, as British forces entered enemy controlled waters, two German sea planes were sighted by SYDNEY at 0933, diving towards HMAS MELBOURNE. Both planes dropped bombs although no hits were scored. The SYDNEY's Sopwith Camel was launched at 0955, together with the MELBOURNE's at 1000 to find and engage the German planes. MELBOURNE's pilot Lieutenant L. B. Gibson, failed to locate the enemy sea planes and soon returned. SYDNEY's pilot, Lieutenant A. C. Sharwood, on the other hand, persued the Germans for nearly sixty miles before he was able to engage them, shooting one of them down and being forced to bail out himself when he failed to relocate the SYDNEY. Sharwood's claim of one enemy sea plane having been shot down was not recognized by the Admiralty on the grounds that there was no independent corroboration. The incident did, however, serve to confirm Dumaresq's faith in aircraft.

SYDNEY was present at the surrender of the German Grand Fleet on 21 November, 1918. She sailed from Portsmouth on 9 April, 1919, for the return passage to Australia. Other than visits to New Guinea in 1922 and New Caledonia and the Solomons in 1927, SYDNEY spent the remainder of her seagoing career in home waters, serving as flagship to the Australian Squadron from September, 1924 until October, 1927. She paid off at Sydney on 8 May, 1928. On 10 January, 1929, she was delivered to Cockatoo Island, Western Australia for breaking up.

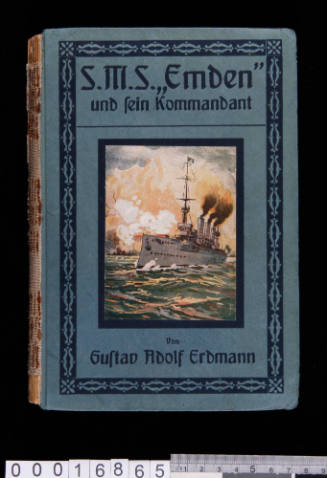

SMS EMDEN was a German light cruiser, launched on 26 May 1908, and commissioned into the German Imperial Navy on 10 July 1909. As a light cruiser she was designed, not to fight other warships, but to disrupt merchant shipping; she was armed with ten 4.1inch (105mm) guns and was the last German cruiser to be equipped with reciprocating engines (subsequent vessels were equipped with steam turbines). Like most ships of the time, the EMDEN's twelve boilers were heated by burning coal, which had to be constantly shoveled into the fireboxes manually by stokers.

On 31 July 1914 SMS EMDEN left Tsingtao (a German colony between 1898 and 1914 that is now known as 'Qingdao' and is a port in Shandong Province, China). She was at sea when she learnt of the outbreak of war on 2 August 1914. She was captained by Lieutenant Commander Karl von Müller, a shy and withdrawn man who was, nevertheless, regarded with great reverence by his crew. He spent most of his time on the bridge and comfortable chairs were placed there for him to sleep and rest in between action and emergencies. He maintained a constant state of readiness aboard his ship, adding extra lookouts after darkness and ordering gun and torpedo crews to be stationed at their posts around the clock.

It took EMDEN some time to reach its desired destination in the Indian Ocean and once there her fighting career was short, lasting barely two months. On 10 September 1914 she captured her first prize; on 9 November the cruiser was a wreck on the shoals of Cocos Island (now part of the Australian territory known as the 'Keeling' or 'Cocos' Islands in the Indian Ocean; halfway between Australia and Sri Lanka). Her first prize, the Greek steamer PONTOPOROS, though an officially neutral ship, was ferrying Allied coal supplies to India. To solve the dilemma von Müller persuaded the Greek captain that German money was just as good as British and that he should now consider himself under charter to the German Government. The PONTOPOROS, together with the EMDEN's stalwart collier (a naval coal transport) the MARKOMANNIA would stay in regular contact with EMDEN until 12 October 1914 when the former ship was captured and the latter sunk by the British Town class light cruiser HMS YARMOUTH.

Although its fighting career was relatively short-lived, the EMDEN quickly built up a fearsome reputation in and around the Indian Ocean's shipping lanes. The ship's chief officer Lieutenant Captain Hellmuth von Mücke arranged for the ship to be disguised by fashioning a false funnel out of sail-cloth canvas and bamboo stakes that was capable of spewing chemically-produced smoke when necessary. Whereas the German cruiser only had three funnels, British cruisers had four and the EMDEN was now able to pass itself off as the YARMOUTH which was also known to be in the area. It was a ruse that proved effective time and time again. On 10 September 1914 the 4000 ton passenger-cargo ship INDUS was captured and sunk en route from Calcutta to Bombay; the 6000 ton LOVAT suffered the same fate not long after.

All in all the EMDEN successfully captured and/or sunk around twenty seven ships during its wartime service. The crew often had the luxury of enjoying many of the spoils of their raids and the prisoners they took, as was the case for most German surface vessels during the war, were treated well and usually ended up being set free. Von Müller was under no illusions, however, as to the fait which awaited his ill-equipped raider; the run of luck he had was nothing short of miraculous, but it had earned the ship a reputation meaning that a confrontation with another warship at some point was inevitable. The world was reading daily reports of his exploits and by late September there were known to be seven British ships, three Japanese vessels and an old Russian cruiser combing the Indian Ocean in search of the EMDEN. It is a testament to the German ship together with the ability of its officers (which included the Kaiser's nephew, Prinz Franz Joseph of Hohenzollern as second torpedo officer) that it was, in actual fact, an Australian ship that would eventually corner and sink EMDEN over a month later.

HMAS SYDNEY was a Chatham class light cruiser of the Australian Royal Navy. It was launched on 29 August 1912 and commissioned on 26 June 1913 at Portsmouth, England.

Following the outbreak of World War One on 4 August, 1914, SYDNEY was stationed in New Guinea and Pacific waters, taking part in the brief campaign to capture Germany's Pacific colonies. Highlights during this period included the capture of Rabaul (a township and headquarters of German New Guinea) and the destruction of Angaur Island Wireless Station, both in September 1914. In October, SYDNEY and her sister ship HMAS MELBOURNE detached from the Flagship HMAS AUSTRALIA to return to Australia. They were to form part of a unit assigned to escorting the first ANZAC convoy across the Pacific and into the Indian Ocean. The convoy consisted of SYDNEY, MELBOURNE, HMAS MINOTAUR and the Japanese cruiser IBUKI, together with thirty-eight transports. It set sail from Albany, Western Australia, on 1 November, 1914 and was timed to pass some fifty miles east of the Cocos Islands on the morning of 9 November, 1914.

Direction Island is part of the Cocos Island group in the Indian Ocean. In 1914 it was managed by the Eastern Extension Telegraph Company which had built a relay station there and from the Cocos the submarine cables ran to Weltevreden in the Dutch East Indies, to Perth in Australia and to Rodriguez Island near Mauritius and thence to Africa. During wartime its strategic importance was immense and it was for this reason that on 9 November 1914 the Emden was sighted off the island. Von Müller's primary objective was to disrupt British communications, although he also planned to harry shipping coming out of Western Australian ports and to create the same sense of dislocation which he had managed in the Bay of Bengal when essential supplies were held in ports for fear of the EMDEN. What the German captain was unaware of, however, was that when he reached the Cocos Islands he had passed within eighty-eight kilometers of the ANZAC convoy. Supposing the coast to be clear, he ordered von Mücke to take a party of fifty men ashore to destroy the cable and wireless stations and, if possible, to cut the cables.

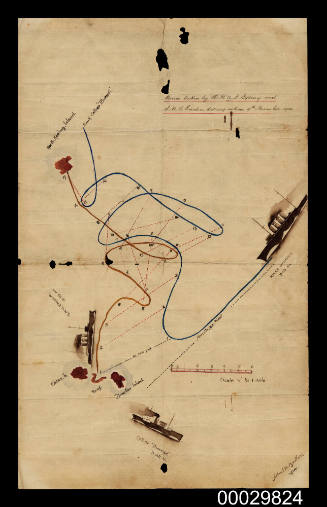

At around 6.20am, wireless telegraphy operators aboard several transports as well as the warships of the ANZAC convoy picked up the message 'Kativ Battav', followed from a query from the Cocos Island Wireless Station asking 'What is that code?' The EMDEN was signaling her collier BURESK to rendezvous with her at Point Refuge. Shortly afterwards Cocos sent out a distress signal that read 'Strange warship approaching.' Although the Emden attempted to jam the signal with its powerful Telefunken equipment, the close proximity of the ANZAC convoy meant it was able to get through the interference and it was shortly followed by 'SOS, Emden here.' After some argument over which ship should break away from the convoy to engage the EMDEN it was decided that the SYDNEY was on the side that was closest to the Cocos Islands and it was capable of doing at least three knots more than the Japanese heavy battle cruiser IBUKI. By 7am SYDNEY was 'away doing twenty knots' and at 9.15am the island, together with the EMDEN were spotted some seven or eight miles distant.

When the SYDNEY arrived von Mücke's wireless-wreckers had already been ashore for some time. They had met with little resistance and had posted men to each of the buildings. The key operator had continued to send out messages right up until the moment he was captured and the last words that went down the cables were 'They are entering the door.' The staff were assembled and placed under guard, while all the papers from the wireless hut were collected for transport back to the EMDEN. The wireless and cable equipment was destroyed by axe and by hand, tables and chairs were overturned and holes were drilled in the base of the wireless mast into which dynamite was placed. After the mast came down, the Germans turned to destroying the engine room, the switchboards and even the seismograph. They attempted to cut the cables, although work was abandoned when siren blasts were heard from the EMDEN recalling the landing party. Having sighted the SYDNEY, the German ship was already busy working up steam and preparing to get under way.

The events which subsequently unfolded have been referred to as the 'Battle of Cocos.' Despite the EMDEN's reputation within the German Imperial Navy for the speed and accuracy of her gunnery, her 105mm guns were simply outmatched by the SYDNEY's 150mm armament. The former began to fire at an impressive rate of one salvo every six seconds, when the latter was still ten kilometers away; this meant she had three salvos in the air at any one time. One drawback of this, however, was that the elevation of her guns was at thirty degrees, meaning that her shells took longer to reach the target than the SYDNEY's which, because of her larger caliber guns, was able to fire the same distance at a lower elevation. Furthermore, the SYDNEY's armour plating was less vulnerable at long range than the EMDEN's.

The battle lasted an hour and a half. The EMDEN's first salvo was ranged along an extended line but every shot fell within two hundred yards of the SYDNEY. The next salvo was on target and for the next ten minutes the Australian cruiser came under heavy fire. Fifteen hits were recorded but fortunately 'only five burst.' Four ratings were killed and several wounded. When the EMDEN's guns were finally silenced von Müller decided to run the ship aground on North Keeling Island in a bid to save his crew members who were still alive. The captain of the SYDNEY estimated that he had scored around a hundred hits on the EMDEN by the time it ran aground. 134 of the Emden's crew were killed in the battle. While some of the survivors were sent to Australian POW camps, the majority, including Müller were imprisoned on Malta.

The EMDEN, wrecked but still somewhat intact, was left to disintegrate on North Keeling Island, until a visitor to the Cocos group in 1919 reported that almost all traces of the ship had disappeared. It is interesting to note that von Mücke's landing party never made it back to the EMDEN and, making off in the schooner AYESHA, managed to escape back to Germany!

SignificanceThe account by the commanding officer of HMAS SYDNEY of its victory against the German raider SMS EMDEN in the First World War was contained within this envelope.

Radfords Crown China

1914-1918