Electric samovar

Datec 1920

Object number00054887

NameSamovar

MediumNickel plated copper alloy

DimensionsDisplay dimensions: 360 x 260 x 280 mm

ClassificationsTableware and furnishings

Credit LineAustralian National Maritime Museum Collection Gift from Natalie Seiz

DescriptionThis electric samovar (Russian tea urn), while never used, was painstakingly polished and had pride of place on the mantelpiece in Katherine Seiz's Sydney home when the family migrated from China to Australia.HistoryWhite Russians Katherine and Ilija Seiz Ptrosrnia fled to Harbin, China, in 1918 after the Bolshevik Revolution. They were accompanied by Katherine's stepsister Alexandria and her brother Victor. In 1919 Ilija, with Englishwoman Miss J Wright, founded the Wright and Ptrosrnia's English Language School in Harbin. The school was registered with the British Consulate and operated until 1942, when it was closed by the Japanese. Ilija assisted other Russians living in Harbin to apply for visas for Australia and South America. He was harassed by the police in Harbin and branded a spy working for Britain and the United States.

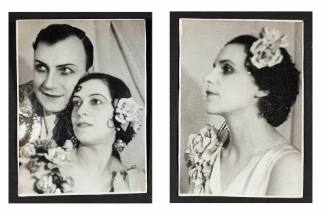

Katherine Seiz Ptrosrnia was a homemaker, while her sister Alexandria performed with a Manchurian dance company. In 1929 Katherine gave birth to her only son Eugene, who attended his father Ilija's English school. Eugene married in Harbin and his first son George died in infancy.

Harbin in north China was once the heart of a vibrant Russian community of diverse cultural and political origins. However by the mid-1930s, the Japanese occupation of Manchuria drove many Russians to seek refuge elsewhere. For the thousands who returned to the Soviet Union, it was a bitter homecoming. At the height of Stalin's purges, they were arrested as Japanese spies. Some were shot, while others were sent to labour camps. Few survived.

The Seiz family was forced to flee China after the Communist Revolution and establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949. They were given the choice of Brazil or Australia. The donor Natalie Seiz (Katherine and Ilija's granddaughter) believes that another Russian family sponsored them to migrate to Australia in 1955 on SS TJIBADAK. They left under tragic circumstances. The rest of the extended family (including Katherine's stepsister and brother) had perished from tuberculosis.

Upon arrival in Australia, the word 'stateless' was stamped on the Seiz family's immigration papers, despite the fact that they had lived in both Russia and China. In Sydney the family lived in a house in Washington Street, Bexley. Ilija worked as a trimmer at the Dunlopillo factory in Bankstown, Katherine found work in the kitchens at the Imperial Service Club in Barrack Street and Eugene established the Abode real estate agency. Ilija died in 1962.

In Australia, Eugene separated from his wife. On a trip to Hong Kong, he met his second wife and they had two children, Natalie and Andrew, before separating. After Eugene died in 1979, Natalie was largely raised by her grandmother Katherine.

Katherine Seiz spoke little English and consequently communicated with her grandchildren in broken English. She was an active member of the Russian Catholic congregation in Sydney, particularly the Croydon church attended by émigrés from Harbin. Katherine died in 1990.SignificanceThe samovar reflects not only Katherine Seiz's attachment to her homeland and a distant life in Russia, but also to uncertain lives in between before she arrived in Australia in 1955.

Melbourne Steamship Company Limited

1935-1960

Before 1857

Before 1857