RNAS MULLION

Subject or historical figure

Sir Lionel Hooke

(Australian, 1895 - 1974)

Date1917-1918

Object number00056171

NamePhotograph

MediumPaper

DimensionsOverall: 185 × 240 mm

ClassificationsPhotographs

Credit LineAustralian National Maritime Museum Collection Gift from Maria Teresa Savio Hooke OAM

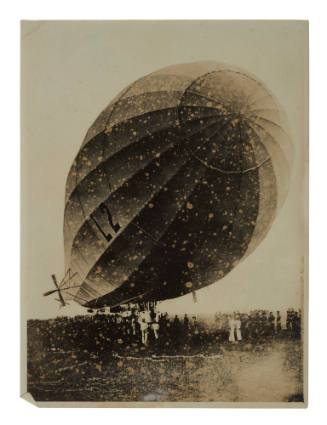

DescriptionAerial photograph of Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) MULLION taken from an RNAS airship.

The photo shows a landscape of large fields, two large aircraft hangers, planes, trucks, houses, and rows of tents.HistoryThe airbase shown in this photograph is likely RNAS MULLION, the largest of four airbases in south west England during WW1. Known as ‘the Lizard’ airship station due to its location at Bonython on the Lizard Peninsula, MULLION was operational from 1916 to 1919. It was distinguished by its two large airship hangars and was used as a base for non-rigid Coastal Class C2 and C9 airships as well as for fixed-wing aircraft. A larger counterpart to the Sea Scout Zero airships, the Coastal Class had a more powerful engine and additional support crew, and engaged in submarine hunting, mine spotting, and fleet escort duties.

Lionel Hooke(later Sir Lionel) was posted to the RN training college at Cranwell in 1917, where he was assigned to airships due to his anti-submarine experience. Hooke’s course focused on free ballooning, airship operations and handling procedures, and instruction on the supervision of maintenance personnel.

Upon completion of his training at Cranwell Hooke was posted to the RNAS airship sub-station at Bude, on the coast of Cornwall. This was one of three sub-stations attached to the main base at Mullion, the others were located in Laire, near Plymouth and Toller, on the north coast of Dorset. Hooke served at all three sub-stations and was for a period Commanding Officer at Bude.

Each of the three substations held up to two Sea Scout - S.S. Zero airships, primarily tasked with submarine hunting and mine spotting duties in an area extending along the southern coast of England to the French Coast. Further operations occurred along the Bristol Channel. The airships would also participate in escorting convoys, however this was primarily carried out from air base Mullion. Hooke flew out on a number of patrols, operations that would begin before dawn and last from 10 to 14 hours.

In an interview in 1974, Hooke described the standard procedure of an airship mission

'We made regular patrols of those areas that were known to be most suitable for enemy submarine operations. These were generally limited to within 50 miles of the coast, because the Germans preferred to work close inshore and obtain visual sights from points along the coastline as aids to their navigation. When planning our patrols we paid particular attention to shipping routes and movements, and, most importantly, the time of day. This gave us the tremendous advantage of getting the morning or evening sun behind us and thus making it easier for us to see, without being seen. It was for this reason that we left our base so early in the morning and flew well out to sea before the sun rose.

Anti-submarine and mine spotting patrols were mostly flown at a height of around 2,000 feet. We could usually depend upon a 25 to 30 knot breeze at that altitude, which enabled us to control our speed range at anything between 25 and 75 knots, according to the circumstances. By heading the ship into the breeze and throttling back the engine, it was possible to remain stationary over a given spot, yet still maintain sufficient airspeed over the rudder and elevators for complete control of the ship. The manoeuvrability of our airships, together with the tremendous range of visibility which they provided, made them perfect observation platforms.'

In September 1918 Hooke’s airship was shot down in the English Channel by friendly fire on his last flight of WWI. A minesweeper misfired during a routine mine disposal operation, catching the envelope of Hooke’s airship. After a short period in hospital with pneumonia Hooke was sent to the Scilly Isles on his last RN posting, supervising the cleaning up of a partly constructed aerodrome near St Marys.

Hooke returned to Australia in 1919 to Amalgamated Wireless Australasia where he was pivotal in the development of live radio broadcasts, direct wireless telegraphy, and the design of the automatic distress transmitter (patented 1929) – forerunner of the EPIRB. In 1945 Hooke became managing director and in 1962 succeeded his friend and mentor Sir Ernest Fisk as chair of AWA. He was awarded a knighthood in 1957 for his services to industry and coronation medals in 1937 and 1953.

Hooke retained a long-lasting interest in airship operation, remarking shortly before his death in 1974:

'On a final note, you might be interested to note that during WWII some serious consideration were given to the building of a fleet of small airships, similar to the Zeros, for patrol work in Australia coastal waters. This scheme did not eventuate but I believe that it was a good idea and would have proven successful – as evidenced by the US Navy blimps around the American coastline' – Lionel Hooke

(Quotes sourced from the 1418 Journal, published by The Australian Society of World War One Aero Historians 1975-6, Chapter by EA Watson on Lionel Hooke, inclusive of complete oral history account with Hooke. Held in Vaughn Evans Library)

SignificanceThis photograph provides a rare perspective of one of the four RN airship bases once present in the south west of England, the structural remnants of which now long lost. The image gives detail on the layout of the base, the buildings and tents present, and aircraft in operation. It is significant in profiling the operational activity RNAS airships, information that is relatively scarce due to the dissolution of the service following World War One.