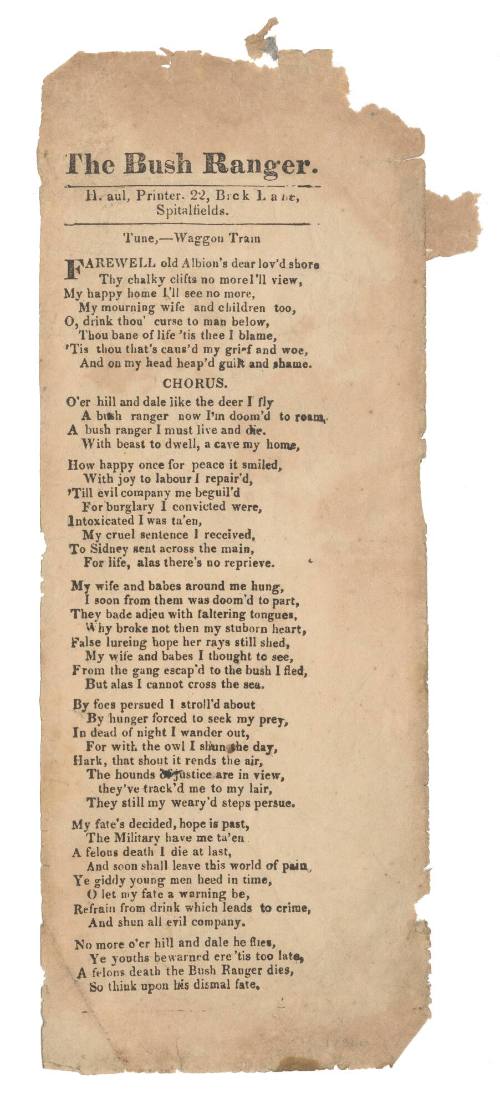

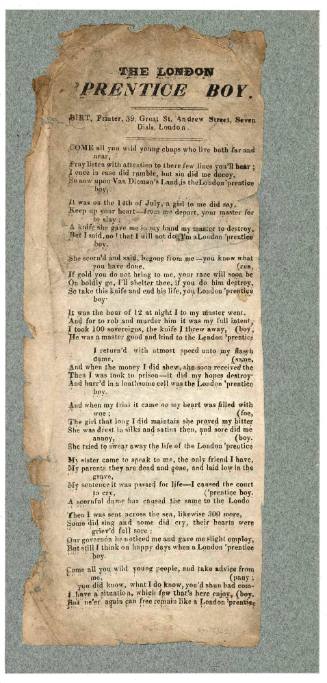

Ballad 'The Bush Ranger'

Printer

Henry Paul printer

(1839 - 1845)

Date1839 - 1845

Object number00017360

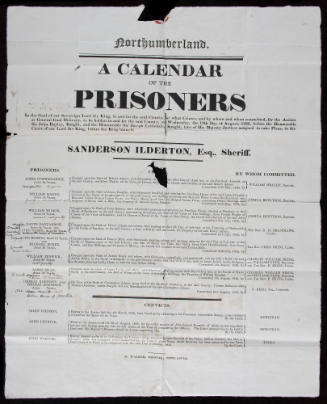

NameBroadsheet

MediumInk on paper

DimensionsOverall: 245 x 95 mm, 0.023 kg

ClassificationsEphemera

Credit LineANMM Collection

DescriptionSung to the tune 'Waggon Train' the ballad is cautionary tale against drinking. Its hero is led into crime through intoxication and bad company. After committing a burglary he is sentenced to transportation for life to Sydney, leaving his beloved wife and children behind. Escaping from the work gang into the bush he is forced to become a Bush Ranger as he cannot escape over the sea to his family in England:

'A bush ranger now I'm doomed to roam, A bush ranger I must live and die. With beast to dwell, a cave my home'

He leads the lonely life of a fugitive until captured and sentenced to death. His parting advice is to steer clear of alcohol:

'O let my fate a warning be, Refrain from drink which leads to crime, And shun all evil company'.

HistoryThe Bush Ranger. Tune, Waggon Train.

FAREWELL old Albion's dear lov'd shore,

Thy chalky clifts no more I'll view,

My happy home I'll see no more,

My mourning wife and children too,

O, drink thou' curse to man below,

Thou bane of life 'tis thee I blame,

'Tis thou that's caused my grief and woe,

And on my head heap'd guilt and shame.

CHROUS

O'er hill and dale like a deer I fly

A bush ranger now I'm doomed to roam

A bush ranger I must live and die.

With beast to dwell, a cave my home,

How happy once for peace it smiled,

With joy to labour I repair'd,

'Till evil company me beguil'd

For burglary I convicted were,

Intoxicated I was ta'en,

My cruel sentence I received,

To Sidney sent aross the main,

For life, alas there's no reprieve.

My wife and babes around me hung,

I soon from them was domm'd to part,

They bade adieu with faltering tongues,

Why broke not then my stuborn heart,

False lureing hope her rays still shed,

My wife and babes I thought to see,

From the gang escap'd to the bush I fled,

But alas I cannot cross the sea.

But foes persued I stroll'd about

But hunger forced to seek my prey,

In dead of night I wander out,

For with the owl I shun the day,

Hark, that shout it rends the air,

The hounds of justice are in view,

They've track'd me to my lair,

They still my weary'd steps persue.

My fate'sdecided, hope is past,

The Military have me ta'en

A felons death I die a last,

And soon shall leave this world of pain

Ye giddy young men heed in time,

O let my fate a warning be,

Refrain from drink which leads to crime,

And shun all evil company.

No mor o'er hill and dale he flies,

Ye youths bewarned ere 'tis too late,

A felons death the Buh Ranger dies,

So think upon his dismal fate.

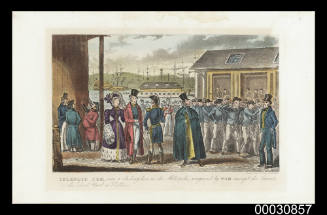

Convicts often invented songs about bushrangers, who were often escaped convicts who, forced to live off the land, were reduced to stealing from settlers and travellers. Many of these 'bush ballads' give a romanticised view of life in the Australian bush and the life of a bush ranger. These ballads continued to be sung as anthems of defiance for decades.

Broadsheets or broadsides, as they were also known, were originally used to communicate official or royal decrees. They were printed on one side of paper and became a popular medium of communication between the 16th and 19th centuries in Europe, particularly Britain. They were able to be printed quickly and cheaply and were widely distributed in public spaces including churches, taverns and town squares. Their function expanded as they became used as a medium to galvanise political debate, hold public meetings and advertise products or cultural events.

The cheap nature of the broadside and its wide accessibility meant that its intended audience were often literate individuals but from varying social standings. The illiterate may have also had access to this literature as many of the ballads were designed to be read aloud. In 'Popular Culture in Seventeenth-Century England', Peter Burke notes that the golden age of the broadside ballad, between 1600 and 1700, saw ballads produced at a penny each which was the same price for admission to the theatre.

The ballads also covered a wide range of subject matter such as witchcraft, epic war battles, murder and maritime themes and events. They were suitably dramatic and often entertaining, but as James Sharpe notes, also in 'Popular Culture in Seventeenth-Century England', some of them were designed as elaborate cautionary tales for those contemplating a life of crime.

The broadside ballads in the museum's collection were issued by a range of London printers and publishers for sale on the streets by hawkers. They convey, often comically, stories about love, death, shipwrecks, convicts and pirates. Each ballad communicates a sense that these stories were designed to be read aloud for all to enjoy, whether it was at the local tavern or a private residence.SignificanceBroadsheets were designed as printed ephemera to be published and distributed rapidly. This also meant they were quickly disposed of with many of them not surviving the test of time. The museum's broadsheet collection is therefore a rare and valuable example of how maritime history was communicated to a wide audience, particularly in the 18th and 19th centuries. They vibrantly illustrate many of the themes and myths surrounding life at sea. Some of them also detail stories about transportation and migration.William James Hall

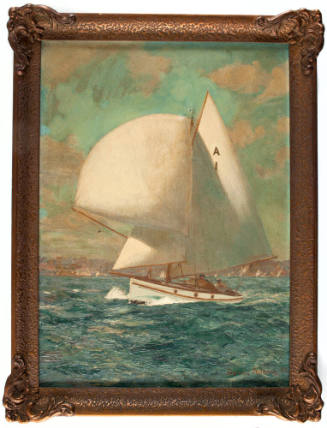

1890s - 1930s

2016