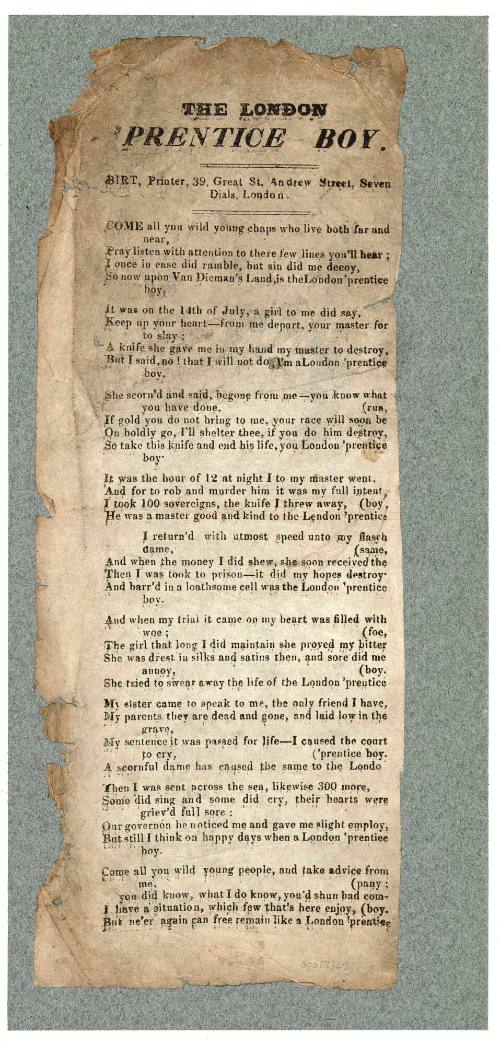

Ballad 'The London Prentice Boy'

Printer

Thomas Birt

(1824 - 1841)

Date1824-1841

Object number00017362

NameBroadsheet

MediumWoodcut engraving and printed text on paper mounted on card.

DimensionsOverall: 256 x 99 mm, 0.023 kg

ClassificationsEphemera

Credit LineANMM Collection

DescriptionIn 'The London Prentice Boy' an apprentice is encouraged by a young woman to steal from his employer and murder him, otherwise her favours would be withdrawn. He steals 100 sovereigns, but does not murder his master who is good and kind. Though turning over his takings to the young woman she gives evidence against him at this trial, only his sister speaking in his support. He sentenced to transporation to Van Dieman's Land, never to be free again. His advice to young people 'shun bad company'.HistoryTHE LONDON 'PRENTICE BOY.

COME all you wild young chaps who live both far and near,

Pray listen with attention to there few lines you'll hear;

I once in ease did ramble, but sin did me decoy,

So now upon Van Diemen's Land, is the London 'Prentice boy.

It was on the 14th of July, a girl to me did say,

Keep up your heart -- from me depart, your master for to slay ;

A knife she gave me in my hand my master to destroy,

But I said, no! " that I will not do, I'm a London 'prentice boy.

She scorn'd and said, begone from me --you know what you have done,

If gold you do not bring me, your race will soon be run.

On boldly go, I'll shelter thee, if you do him destroy,

So take this knife and end his life, you London 'prentice Boy."

It was the hour of 12 at night, I to my master went,

All for to rob and murder him, it was my full intent;

I took 100 sovereigns, the knife I threw away,

He was a master good and kind, to the London 'prentice boy.

I return'd with utmost speed unto my flashy dame,

And when the money I did shew, she soon received the same,

Then I was took to prison -- it did my hopes destroy,

All barr'd in a lonesome cell was this London 'prentice boy.

And when my trial it came on my heart was filled with woe,

The girl that long I did maintain she proved my bitter foe,

She was drest in silks and satins then, and sore she did annoy,

She tried to swear away the life of the London 'prentice boy.

My sister came to speak to me, the only friend I have,

My parents they are dead and gone, and laid low in the grave,

My sentence it was passed for life -- I caused the court to cry,

A scornful dame that caused the same to the London 'prentice boy.

Then I was sent across the sea, likewise 300 more,

Some did sing and some dis cry, their hearts were griev'd full sore ;

Our governon he noticed me and gave me slight employ,

But still I think on happy days when a London 'prentice boy.

Come all you wild young people, and take advice from me,

you did know, what I do know, you'd shun bad company ;

i have a situation, which few that's here enjoy,

But ne'er again can free remain like a London 'prentice boy.

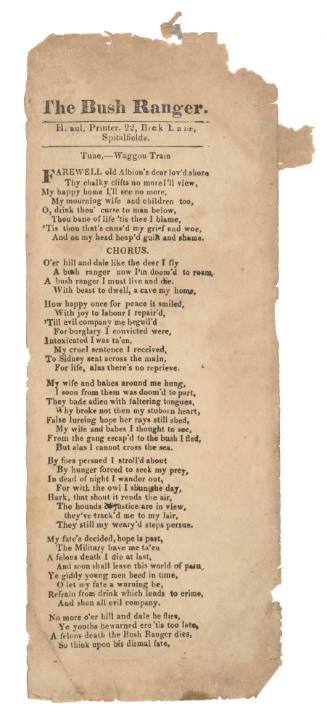

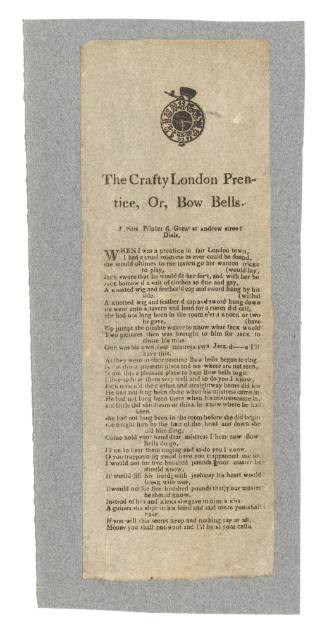

Broadsheets or broadsides, as they were also known, were originally used to communicate official or royal decrees. They were printed on one side of paper and became a popular medium of communication between the 16th and 19th centuries in Europe, particularly Britain. They were able to be printed quickly and cheaply and were widely distributed in public spaces including churches, taverns and town squares. Their function expanded as they became used as a medium to galvanise political debate, hold public meetings and advertise products or cultural events.

The cheap nature of the broadside and its wide accessibility meant that its intended audience were often literate individuals but from varying social standings. The illiterate may have also had access to this literature as many of the ballads were designed to be read aloud. In 'Popular Culture in Seventeenth-Century England', Peter Burke notes that the golden age of the broadside ballad, between 1600 and 1700, saw ballads produced at a penny each which was the same price for admission to the theatre.

The ballads also covered a wide range of subject matter such as witchcraft, epic war battles, murder and maritime themes and events. They were suitably dramatic and often entertaining, but as James Sharpe notes, also in 'Popular Culture in Seventeenth-Century England', some of them were designed as elaborate cautionary tales for those contemplating a life of crime.

The broadside ballads in the museum's collection were issued by a range of London printers and publishers for sale on the streets by hawkers. They convey, often comically, stories about love, death, shipwrecks, convicts and pirates. Each ballad communicates a sense that these stories were designed to be read aloud for all to enjoy, whether it was at the local tavern or a private residence.SignificanceBroadsheets were designed as printed ephemera to be published and distributed rapidly. This also meant they were quickly disposed of with many of them not surviving the test of time. The museum's broadsheet collection is therefore a rare and valuable example of how maritime history was communicated to a wide audience, particularly in the 18th and 19th centuries. They vibrantly illustrate many of the themes and myths surrounding life at sea. Some of them also detail stories about transportation and migration.