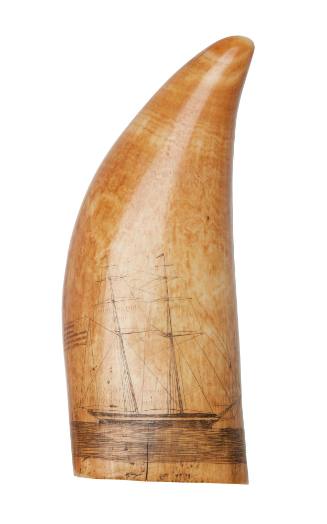

Whaling scene and a tropical island - scrimshawed whale tooth

Date19th century

Object number00042491

NameScrimshaw

MediumSperm whale tooth

Dimensions92 x 222 x 55 mm

ClassificationsDecorative and folk art

Credit LineANMM Collection

DescriptionA large scrimshaw sperm whale tooth. One side depicts a ship alongside two sperm whales and a whaleboat. Above them are seven sea birds. At the tip of the tooth a face in profile is depicted, which is repeated verso.

The reverse side depicts three small rowboats and a three masted barque with palm trees along a shoreline suggesting a Pacific Ocean location. A simple leaf design runs along the top and bottom of each scene. Both ships depicted appear to be flying British flags.HistoryScrimshaw was the carving done by seamen in whaling ships on the jawbones and teeth of whales and the tusks of walruses. The term has also been extended to include carvings on bone from other sources, horn and shell, when the subjects are maritime. Most scrimshaw is naive in execution, and seamen were commonly illiterate. It is rare to find scrimshaw with dates and names of makers, although names of ships were sometimes given. It is often impossible to date scrimshaw or to establish the nationality of the carver. The whaling period extended from about the 1780s to the 1890s, with a hiatus in the mid-nineteenth century when whaling declined for a period before factory ship operations began about the 1870s. Seamen used any sharp implement they could find to incise designs. The tip of their knife was the basic tool, but they also used needles and any other kind of tool they could improvise. They used anything from soot to ink or paint to colour the lines. They often pricked out the outline of a design, tracing from a picture, and joined up the dots. The scrimshaw powder horn includes pinprick hatching in the bodies of the birds, and all the lettering is made up of pricked dots.

No specific historical background can be ascribed to the sperm whale tooth, except that the two ships illustrated appear to be flying the British flag. The detail of the ships and of the whaling scene shows first hand knowledge, so the carving is clearly the work of a seaman. The ships themselves, and the scene with the barque, palm trees and mountain have the character of the earlier whaling period, possibly even late 18th century, suggestive of Pacific exploration.

The scrimshaw powder horn (00042490) from the same acquisition carries a wealth of information, but also mystery. The name Louis M H(?) Gauvin is almost certainly Louis Gauvin who was at Dalby and Paroo in Queensland between 1868 and 1883, over which time he is believed by a descendant to have fathered six children. The inscription TAMBO BARCOO refers to the town of Tambo, originally a property of that name, on the Barcoo River in south central Queensland. It was gazetted a town in 1869, the year before the date on the powder horn. Tambo is in the same general region as Dalby, Paroo and Charters Towers where the Gauvin family eventually settled. One of Gauvin's grandsons, George Pollock, was Speaker in the Queensland Parliament in the 1930s and other descendants live in Queensland.

However, no record has been found of Gauvin's birth, arrival in Australia, marriage or death. Family lore among his descendants associates him with Marshal Ney, the head of Napoleon's army, who was executed in 1815, even to the extent of believing him to be Ney's son. There is a long established belief that Ney's execution was faked and that he was helped to escape to the United States by the British and by freemasons - Ney himself being a freemason. The masonic symbols on the horn clearly had strong significance for Gauvin, assuming he was the carver. The design appears to be celebrating or urging union between France and England, in a masonic framework. The ship on one side of the powder horn is flying both a French and English flag, the same two flags which appear on the other side of the horn as part of a structure enclosing the word UNION. The 'all seeing eye' is a masonic symbol referring to God or the Grand Geometrician of the Universe. The crossed set square and compass (which appears twice) is one of the most basic masonic symbols - architect's tools which symbolise God as the Architect of the Universe. The words PEACE, JOY, PLENTY, and PROSPERITY, FAITH, HOPE, CHARITY, have significance in masonic rituals, and the Latin words GRATIAS AGAMUM DOMINI DEO NOSTRO, mean 'Let us thank our Lord and God'. This is one of the responses in the Latin Mass, and it is also a sentence used in masonic ritual.

The Louis M H Gauvin of the powder horn may possibly have been a seaman named Gauvin who was listed in official records as an unassisted arrival in Sydney on 22 October 1846, after surviving the wreck of the French whaling ship COLON at Banks Peninsula, off New Zealand. The Sydney Morning Herald reported on 26 September 1846 that the COLON had been wrecked at Pariki, and that the brig BEE had been chartered at Port Nicholson to proceed to the wreck, to bring the crew and cargo to Sydney. The Herald of 23 October reported the arrival in Sydney the previous day of the BEE, with the captain, officers and crew of the COLON. The Index to Unassisted Arrivals in NSW lists the arrival of a passenger on the BEE named Gauvin, but gives no Christian names. He was described as 'Harponneur [harpooner], FRA, Visitor, Fr wreck French whaler "Colon".'

The possibility that this seaman was Louis M H Gauvin, the carver of the powder horn is very strong, because of the whaling connection. However, Gauvin was listed as a visitor only, and the lapse of 20 years between his arrival in Sydney and the appearance of Louis M H Gauvin having children in Queensland in the 1860s may make it less likely that he was the same person. Further research may yield more information as to his background. It may be that there were two Gauvins, father and son.

The most intriguing question raised by the scrimshaw is the possible connection with Marshal Ney, because of the masonic symbols, the fact that Ney was a freemason, and the designs linking France and England together. The Gauvin family legend was that Gauvin was the son of Marshal Ney who was not executed in 1815 as is recorded in history, but escaped to America. According to this story, his family went to live in Canada taking the name Gauvin. But the Gauvin who arrived in Sydney in 1846 was listed as French, not Canadian or American. However it seems quite possible that a Gauvin ancestor may have been associated with Ney, or fought under him in the Napoleonic wars, and may have been a fellow freemason.

A belief has long existed more generally that Ney's execution was faked, with the help of the British, the Duke of Wellington, and Freemasons (Ney and Wellington were both freemasons). A man calling himself Peter Ney who was a teacher in North Carolina claimed at the end of his life to be Marshal Ney. According to H H Bradshaw in 'Execution Denied, the History of Marshal Ney', a work of historical fiction based on the life of Peter Ney, this man had one son who was a doctor and called himself Neyman. He lived in Indiana. There would appear to be no connection between him and Gauvin.SignificanceThe scrimshaw whale's tooth is an excellent example of its type, being a large intact tooth with an unusual character imparted by the faces on either side of the tip. The detail of the ships and of the whaling scene shows first hand knowledge, and is clearly the work of a seaman. The ships themselves, and the scene with the palm trees and mountain have the character of the earlier whaling period, possibly even late 18th century, suggestive of Pacific exploration. It is significant as an elaborate example of scrimshaw, representing Pacific whaling at a period of importance in Australia's maritime development.

The powder horn is very significant as an intriguing relic of whaling days with a rare, specific Australian connection. The profuse decoration, the words and symbols which appear to tell a story, its Queensland location and the name of the carver, give it great interest. Its purpose could only have been decorative in 1870, because muzzle-loading muskets with which powder horns were used were obsolete by the 1830s. However, whaling ships usually had guns for signalling and protection, and carried gunpowder in cow horns, which were later used by seamen to make scrimshaw. Louis Gauvin, the apparent carver of the horn, must have had experience in whaling ships and learned the art of scrimshaw on them. The connection with the family founded in south-central Queensland in the 1860s and 1870s (see Historical Background) demonstrates the different maritime strands which made up Australian society in the 19th century.