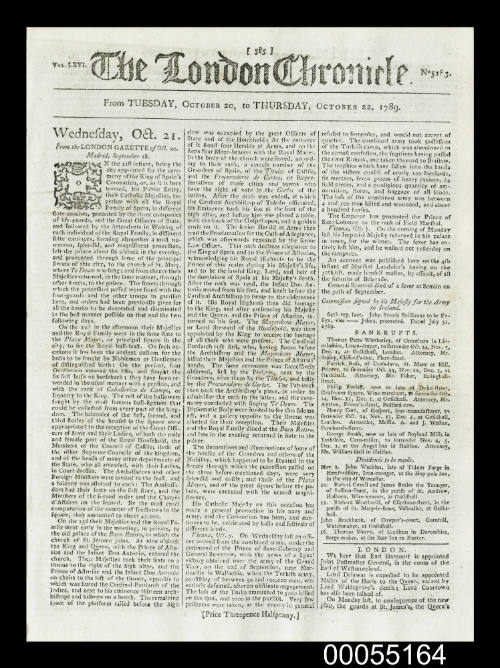

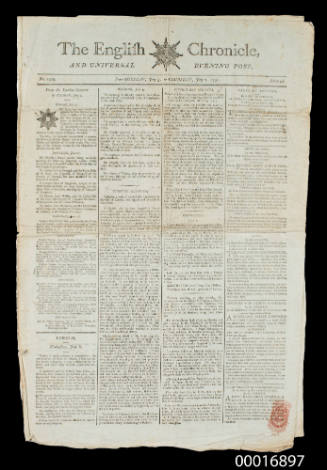

London Chronicle 'Extract of letter from on board the LADY JULIANA, Aitken for Botany Bay'

Date1789

Object number00055164

NameNewspaper

MediumInk on paper

DimensionsDisplay dimensions: 291 × 216 × 1 mm

ClassificationsEphemera

Credit LineANMM Collection funded by ANM Foundation

DescriptionPages 385 - 392 of the London Chronicle Newspaper of Tuesday 20 October to Thursday 22 October 1789, Vol.LXVI, No 5183.

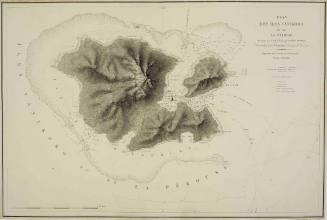

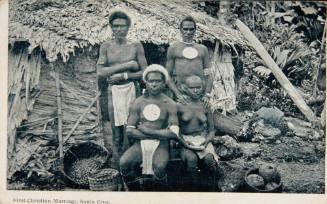

An article on page six is titled 'Extract of letter from on board the LADY JULIANA, Aitken for Botany Bay, dated Santa Cruz, Sept. I'.

Transportation overseas was a relatively common punishment in the 18th and 19th century. This newspaper account relates to the safe arrival of the female convict transport LADY JULIANA at Santa Cruz on September 1, 1789.

HistoryExtreme poverty was a fact of life for many in 18th and 19th century English society. In desperation, many resorted to crimes such as theft, prostitution, robbery with violence and forging coins as the means to survive in a society without any social welfare system or safety net. This was countered by the development of a complicated criminal and punishment code aimed at protecting private property. Punishment was harsh with even minor crimes, such as stealing goods worth more than one shilling, cutting down a tree in an orchard, stealing livestock or forming a workers union, attracting the extreme penalty of 'death by hanging'.

Until the early nineteenth century prisons were administered locally and were not the responsibility or property of central government, with the exception of the King's Bench, Marshalsea, Fleet Prisons and Newgate Gaol, which were all Crown prisons attached to the central courts. They were used for the correction of vagrants and those convicted of lesser offences, for the coercion of debtors and for the custody of those awaiting trial or the execution of sentence.

When in the 18th century, the death penalty came to be regarded as too severe for certain capital offences, such as theft and larceny The British Transportation Act of 1718 effectively established transportation to the American colonies as a punishment for crime. British courts sentenced criminals on conditional pardons or those on reprieved death sentences to transportation.

Prisoners were committed under bond to ship masters who were responsible for the convict's passage overseas in exchange for selling their convict labour in the distant colony. This solution helped solve the overcrowding in British prisons and provided much needed labour for the American colonies of Virginia and Maryland. The American War of Independence (1776-1781) effectively stopped transportation to the Americas leading to the introduction of prison hulks in England and Ireland as temporarary prisons until a solution could be found.

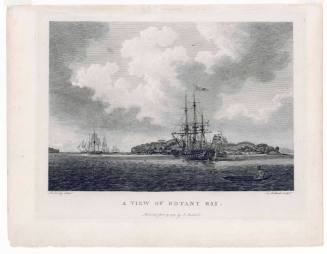

Convict transportation to Australia began in 1787 (New South Wales) reached its peak in the 1830s (New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land) and continued until 1868 (Western Australia) by which time prison reform, relaxation of penalties in the criminal code, the construction of purpose built prisons in Britain and Ireland and growing disenchantment with the convict transportation system saw the cessation of transportation to the Australian Colonies.

Between 1788 and 1868 over 168,000 men, women and children had been transported to Australia from England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, Canada, India, Bermuda and South Africa as convicts on board more than 1,000 modified merchant ships which had been converted into convict transports. Although many of the convicted prisoners were habitual or professional criminals with multiple offences recorded against them, a small number were political prisoners, social reformers, or one-off offenders.

BOTANY BAY & A FEMALE TRANSPORT: THE LONDON CHRONICLE

October 20-22, 1789: A small article but a big story; this edition carries an "Extract of a Letter on board the LADY JULIANA, Aitken, for Botany Bay, dated Santa Cruz, Sept.1" in which the correspondent notes "I have the pleasure of informing you of our safe arrival in this place......We are all in good health; the women have behaved much better than was expected....."

The British government chartered the LADY JULIANA to transport female convicts. Its master was Thomas Edgar, who had sailed with James Cook on his last voyage. The surgeon was Richard Alley, who was apparently competent by the standards of the day, but made little attempt to maintain discipline. The ship took 309 days to reach Port Jackson, one of the slowest journeys made by a convict ship. One reason was that it called at Tenerife and St Jago, and spent forty-five days at Rio de Janeiro, and nineteen days at the Cape of Good Hope. It carried 226 female convicts, five of whom died during the journey. Most of the convicts were London prostitutes, but there were some hardened criminals - thieves, receivers of stolen goods, shoplifters - among them.

The LADY JULIANA gained the reputation for being a floating brothel. Nicol recalled that "when we were fairly out to sea, every man on board took a wife from among the convicts, they nothing loath." At the ports of call seamen from other ships were freely entertained, and the officers made no attempt to suppress this licentious activity. No provision had been made to set the convicts to any productive work during the voyage, and they were reported to be noisy and unruly, with a fondness for liquor and for fighting amongst themselves.

The low death rate during the voyage was due to Edgar and Alley's care. Rations were properly issued, the vessel kept clean and fumigated, the women were given free access to the deck, and supplies of fresh food were obtained at the ports of call. This treatment was in sharp contrast to that meted out on the infamous Second Fleet.

When LADY JULIANA arrived at Port Jackson it was the first vessel to arrive there since the First Fleet's arrival almost two and a half years before. In the grip of starvation, with HMS SIRIUS having wrecked at Norfolk Island, Judge Advocate David Collins was mortified at the arrival of "a cargo so unnecessary and so unprofitable as 222 females, instead of a cargo of provisions". Lieutenant Ralph Clark was blunter, lamenting the arrival of still more "damned whores".

SignificanceThis newspaper account relates to the safe arrival of the female convict transport LADY JULIANA at Santa Cruz on September 1 1789. Described as the 'Floating Brothel' - an historical term brought to light by the social and maritime historian Sian Rees - the LADY JULIANA has become synonymous with all that was wrong with the convict transportation system and reflects the sexual, social and racial stereotyping used by the colonial male elite to describe women in general and convict women in particular - a theme taken up by Anne Summer's in Dammed Whores and God's Police (1975).Royal Interocean Lines

1956

Victor Amadee Gressien

c 1890