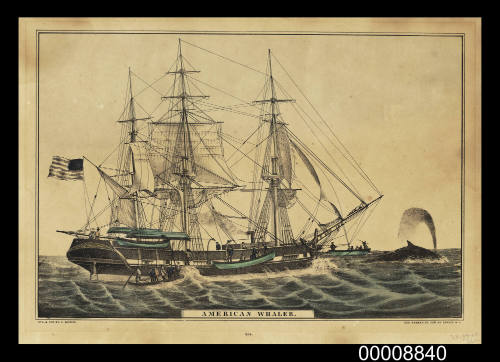

American Whaler

Publisher

Nathaniel Currier

(1813 - 1888)

Lithographer

Nathaniel Currier

(1813 - 1888)

Datec 1850

Object number00008840

NameLithograph

MediumColour lithographic print on paper

DimensionsOverall: 342 x 457 mm, 0.1 kg

ClassificationsArt

Credit LineANMM Collection

Purchased with USA Bicentennial Gift funds

Collections

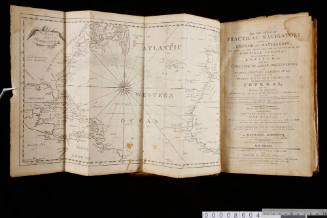

DescriptionHand coloured lithograph of a bark-rigged whale ship, typical of the 1850s, after a painting by Louis le Breton.

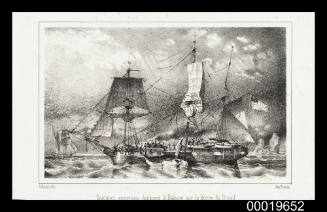

Le Breton was a professional marine artist living in Paris who spent four years in the south seas as official marine painter on the Dumont d'Urville expedition to the South Pole (1837 - 1840). He became familiar with the vessels and methods used in the American whaling industry on that voyage. The print was published by Nathaniel Currier.HistoryLouis Le Breton (1818-1866) joined Dumont d'Urville's 1837-1840 French expedition to the Antarctic as a junior surgeon, but after the death of official artist Ernest Goupil in Hobart in 1840, he was appointed artist for the remainder of the voyage. After returning to France he was given the task of producing the visual accounts of the voyage, an endeavor which took him seven years. During this time he submitted several of his most ambitious paintings inspired by the expedition to the Paris Salon.

Captain Jules Dumont d'Urville was a French naval officer who commanded two voyages of discovery to the Pacific Ocean and to Antarctica during the Bourbon Restoration (1815-1830) and July Monarchy (1830 - 1848).

At an early stage of his naval career Dumont d'Urville participated in a hydrographic survey of the Aegean Sea during which he was instrumental in the recovery for the Musee de Louvre of the 'Venus de Milo'; he later served with distinction as second-in-command to Captain Louis Duperrey during a circumnavigation in the 'corvette' LA COQUILLE (1822 - 1825). D'Urville's next venture would be one he commanded himself. Two months after his return aboard the COQUILLE he presented the Naval Ministry with his plan for a new expedition which would see him returning to the Pacific. It was approved and on 25 April, 1826 the COQUILLE (renamed the ASTROLABE) departed Toulon to circumnavigate the world in a voyage that would last nearly three years.

The ASTROLABE skirted the coast of southern Australia, carried out new relief maps of the South Island of New Zealand, reached the archipelagos of Tonga and Fiji, executed the first relief maps of the Loyalty Islands (part of French New Caledonia), and explored the coasts of New Guinea. D'Urville identified the site of La Pérouse's shipwreck in Vanikoro (one of the Santa Cruz Islands, part of the archipelago of the Solomon Islands) and collected many remains of his boats. The voyage continued with the mapping of part of the Caroline Islands and the Moluccas. The ASTROLABE returned to Marseille in early 1829 with an impressive collection of hydrographical papers and collections of zoological, botanical and mineralogical reports. It was also thanks to this expedition that the terms Micronesia and Melanesia were established to distinguish two very different cultural island groups from Polynesia.

Between 1832 and 1834 the French Government published d'Urville's five volume account of his travels. In January 1837, after finding significant gaps in the exploratory findings of his first expedition, d'Urville wrote to the Naval Ministry requesting permission to undertake another voyage to fill them. His plan was approved, again with an added condition: this time d'Urville was charged with the duty of claiming the South Magnetic Pole for France. If this was not possible, he was to equal the most southerly latitude that had then been achieved by a European explorer (Englishman James Weddell in 1823).

The ASTROLABE together with another ship, the ZÉLÉE (commanded by Charles Hector Jacquinot) were prepared for the voyage at Toulon while d'Urville travelled to London to aquire both documentation and instrumentation. D'Urville's third voyage was plagued with misfortune. Early in the voyage several crewmen were involved in a drunken brawl and were arrested in Tenerife, a stop had to be made in Rio de Janeiro to disembark a sick official and a large quantity of voyage provisions consisted of rotting meat, which had dire consequences for the crew's health. Two weeks after encountering their first iceberg, the two ships found themselves entangled in a mass of ice in January 1838. Over the next two months d'Urville led increasingly desperate attempts to find his way through the ice to the desired latitudes, frequently having to change direction to compensate for the moving ice. Heading towards the South Shetland Islands and the Bransfield Strait, d'Urville located several areas of land in dense fog which he named Terre de Louis-Philippe (now called Graham Land), the Joinville Island group and Rosamel Island (now called Andersson Island).

By February 1838 with conditions on board both ships rapidly deteriorating, d'Urville redirected the ships to Talcahuano, in Chile, where a temporary hospital was established for the large number of crewmen afflicted with scurvy. During the voyage from the East Indies to Tasmania, several of the crew were lost to tropical fevers and dysentery. In December 1839 the two corvettes landed at Hobart where the sick and dying were treated. D'Urville was received by the Governor of Tasmania, John Franklin who informed him that the ships of an American expedition to the south led by Charles Wilkes were currently berthed in Sydney preparing to sail. Plagued by misfortunes and the increasing reduction of his ships' crews due to disease, d'Urville announced that he would leave for the Antarctic with only the ASTROLABE. Captain Jacquinot urged d'Urville to solve the crew situation by hiring replacements (generally deserters from other French vessels) and the latter eventually agreed to sail with both ships in early January 1840. On 19 January 1840, the expedition crossed the Antarctic Circle, with celebrations being held in a similar fashion to that of an equator crossing ceremony. The two ships then sailed west, skirting walls of ice and eventually choosing a rocky island to hoist the French tricolour. D'Urville named it Pointe Géologie and the land beyond, Terre Adélie (Adélie Land, named after his wife).

In the following days the ships followed what it was assumed was the coast, briefly sighting an American schooner from the Wilkes expedition that quickly vanished in thick fog. On 1 February d'Urville decided to return to Hobart. They then went on to the Auckland Islands, where they carried out magnetic measurements leaving behind a commemorative plate of their visit, in which they announced the discovery of the South Magnetic Pole. They returned to France via New Zealand, Torres Strait, Timor, Réunion, Saint Helena and finally Toulon, returning in November, 1840. It would be the last great French expedition of exploration that would ever sail.

SignificanceWhaling vessels were rarely depicted by marine artists. Views of whaling usually focussed on the chase with the whale ship in the background. This accurate and instructive image of the American whaling industry is unusual in that it was painted by a European artist.